Eileen Myles: On Building a Career and the Current State of Poetry

Author: Ricky Tucker

May 8, 2016

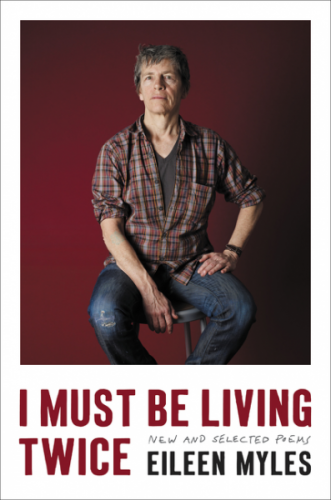

The poet Eileen Myles has arrived at a moment. With the release of her collection, I Must Be Living Twice, the reissue last fall of her lyrical novel, Chelsea Girls, and her inspired cameos on Amazon’s breakthrough comedy, Transparent, her past has met her square in the present — and a time when poetry seems to be at the forefront of literature.

The 2016 Lambda Pioneer Award recipient spoke with us about transitioning: from Boston to New York to Texas, from marginal obscurity to popularity, and from the past to the future–and into love.

They say it takes about a year to promote a new book. I Must Be Living Twice is a collection of your life’s work. How is it different touring with this book compared to your other nineteen books?

It’s sort of like touring all my books at once. It’s weird. It’s more than “Here’s my new work, how do you like it?” It’s like, “How do you like my whole career?” I’ve been getting a lot from this particular tour with Chelsea Girls coming out at the same time. It feels more personal in a way. In my work, I use an “Eileen Myles” character if it’s prose, and in poetry, because I frequently use I, people often align the work with me and assume I’m talking about myself. I am and I am not.

Basically, if you’re doing a reading from books that are your entire career, then it really is about you, because they really are your books even if the poems are not about you. So there’s a funny way in which I’m having a public experience with my own reputation. Happily it’s gone well. If everyone was like “Yes, and you’re a douche bag,” it might not have been such a good experience, but it’s been very different. It’s been a little monumental rather than lyrical, I guess.

I’ve heard your name in the literary world for years, but now it seems a lot more prevalent. Do you think the collection has something to do with that, or did the two just happen to coincide at the perfect time?

If you have an intention, it’s often a growing one. The book before Inferno that was prose was Cool for You, and when I was trying to sell that book with an agent, editors kept saying, “Who is she?” It was kind of like, if this person chooses to use their own name in their work, the presumption is that we know who she is. In a way, when I did Inferno, I thought, I’m going to answer that question by very specifically writing about a person who is a poet. And I still framed it as a novel and used the name Eileen Myles. I feel like I was already doing what Selected and the return of Chelsea Girls has done, which is to look at the whole career.

In Cool for You, I was looking at what it felt like to be female in all these institutions, and one of the institutions I wrote about was writing. I showed people the draft of that book, and they were like, “Ugh. The part about writing….” It wasn’t a great part of the book. I don’t know about you, but often when I’m writing something, my last hole-in-one project becomes the entirety of my next one. So, I intentionally went towards writing a book about a poet, because if you don’t know who this person is, I’m going to tell you. I’m going to tell you what a poem is almost more than who this poet is.

People come to you often to define what today’s poet is. Have you seen more of a popularization of poetry today?

Oh yeah. It’s exploding right now. They call it morphic resonance, when the same thing is invented in different places at the same time. Not one person discovered the microscope, it was discovered all over the place. And I think poetry is having that right now. The art world, for about ten years now, is increasingly proud to say they’re into poetry, that this work by a poet belongs in the Whitney Biennial. That weird little thing interests us now. And of course, social media is just a poet’s paradise in terms of fragmentation, because our art form is so insinuative and we are able to stick-pin it all over the place. Rather than saying, “This is my room,” you just puncture the room in all these ways. I think it’s kind of a weirdly hot profession at this moment in time.

Oh yeah. It’s exploding right now. They call it morphic resonance, when the same thing is invented in different places at the same time. Not one person discovered the microscope, it was discovered all over the place. And I think poetry is having that right now. The art world, for about ten years now, is increasingly proud to say they’re into poetry, that this work by a poet belongs in the Whitney Biennial. That weird little thing interests us now. And of course, social media is just a poet’s paradise in terms of fragmentation, because our art form is so insinuative and we are able to stick-pin it all over the place. Rather than saying, “This is my room,” you just puncture the room in all these ways. I think it’s kind of a weirdly hot profession at this moment in time.

Also, my work is good—it’s always been good. So I think I’m getting a lot of bang for my buck for a lot of reasons. If the work sucked, it wouldn’t really matter at all, it would just be cool that this woman was doing it, you know?

But the work is good, and it happens to be you.

And it happens to be now!

Speaking of pop culture, there was recently a character based on you in the second season of the Amazon Prime series Transparent. How did this come about?

It’s all part of a lovely coincidence. They were writing season two, and they started creating a lesbian poet character. [The character] Ali Pfefferman was going to have a crush on one of her professors, and so I think after writing that plot line, the writers, some of whom I know, said “It should be Eileen Myles.” Then Jill Soloway was like, “Oh, well that’s funny. I’m gonna be on a panel with her in San Francisco with Michelle Tea.” And so we met.

But she had started researching me before we met, and then I met Jill and had a big crush on her on stage. So then I started to get kind of roped in, happily roped in. Jill used a couple of my poems for the character, which is really so interesting. I thought a person can be an actor and play another character, but can a poem be an actor and play somebody else’s poem?

That’s wonderful.

Yeah. So it wound up being Cherry Jones’s Eileen Myles. And then Cherry Jones started researching and listening to recordings of me. We’re approximately the same age. She’s southern, I’m from Boston. She didn’t imitate my accent but she definitely got some of the cadence of the way I read. And then they started interrogating me about how she should dress or how I dress. She started becoming more of a version of me than me, which is really funny. And then they decided I should be a friend of hers on the show. I mean, I’m more of a cameo, but I’m in like three episodes. Then, of course, I had the pleasure of seeing Jill direct on set and be around the whole thing, which is just kind of a fantastic situation. It’s a beautiful incident that I think has something to do with the whole phenomenon we’re describing. Then my work, and then the accident of falling in love with Jill.

It’s so funny, because you started by talking about your collection and saying you’re trying to get acquainted now with your public perception. Transparent seems like another extension of that. It must be a kind of heady time?

I was [referenced] in that Lily Tomlin movie too [Mother] and suddenly I was in [Transparent] as well. It’s just a lot of accidents. I think the thing with an accident is if you are ready to be a part of it, then it’s a really good thing.

Geography plays into a lot of your poems. You’re known as a Boston writer, you’re known as a quintessential New York writer. Am I right in saying that you’ve recently moved to Texas too?

Well, that’s where I’m standing right now. Marfa, Texas is Texas, and it isn’t Texas; how Provincetown is Massachusetts and it isn’t Massachusetts. I’m here because Lannan has these amazing residencies, and I came here last March to do one. I had been hearing about Marfa since forever, and I was like, “I want to go to this place.” I knew it was this kind of artsy town. I came here and I finished a book about my former pit bull, Rosie, and I had such a good experience writing it here. I was single at the time, and it just seemed like the right mix of a few art events or readings a week and an incredible landscape that is not mine. It’s very big and very expansive, and there are lots of opportunities to take beautiful walks. I thought, I could live here in some way and not go out of my mind. You’ve got this southwestern landscape without the sense of feeling like a monk.

So, you found a new writing space. What does Boston do for your writing? What does New York do for your writing, and do you revisit those spaces in order to facilitate those different things they do for you?

Oh yeah, totally. New York is like the charge. New York is like the crucible and the energy. My friends are a huge diaspora at this point in time, and I realized when I go on tour, I get to see my friends all over America. But New York still feels like the place of people from home. And in terms of just the way my evening can unfold culturally in New York. I love New York, and I’ll likely die there. It’s just my place in a way. It gave me me. I mean, I learned how to be a writer in New York. I watched other artists, I learned to survive and make a living. Other people’s hunger helped me to understand my own.

But Boston is my roots. Every time I get up to read, this sound comes out of my mouth. And I’m like, “God,” I think it’s the very fabric of my intelligence. A’s sound like that to me, and when they come out, it’s just like I’m playing my horn. You know, I always wanted to play music, and I think a Boston accent is my music.

You said, I think in the Paris Review, that “Art looks like the Lottery from here.” You were talking about coming from a blue collar, working class perspective. Do you always carry that with you? And if your working class view on art has changed, what’s the view like now?

It’s very different because I’m a part of it now. With that lottery thing, I just didn’t get it in the same way that the economic decks were stacked against me. It meant literally that when I came to New York and met all these other poets of my generation, it seemed like they came more from middle-class backgrounds than me, went to better private colleges. My aspirations, class-wise, were strange for my background, I guess.

But on the other hand, my joke lately is that–I don’t know why I’ve been thinking about this lately–I have a BA in English. So, in a way, I’m the perfectly practical college graduate. I really thought I was going to college so that I could have a career. It’s true, I did. I majored in English so I could become a poet. It was a career decision. As a person in the working class, you’ve got to be practical–and I am a very practical person. So there’s a way in which, in the best way, I’ve never left my roots. I really am them, and I use them, and I use my accent, and I use everything in the way that a bird builds its home out of everything that’s available, and that’s its nest. But also, I think you live in the art world, and you live in the poetry world, and then that becomes your nest too. It becomes where you belong, and you even change its system of belonging, both by your identity and your way of assembling things.

I remember when I was younger just noticing that Jean Cocteau and more contemporary men could do these things all over the place and it would be an illustration of their genius, but it still seemed for a long time that if a women did a lot of different things she was scattered. She wasn’t building a big valid career. A lot of my ways of crab walking from here to there were economic choices. I thought, “I don’t want to stop being a poet, but I’ve got to make a living.” It seemed like one could make a living as a performance artist in the 80s, so I started to memorize my poems, which wasn’t what anybody in the poetry world was doing in the 80s, but it meant then that I could be integrated into the performance art scene that was getting so much more attention–and you could tour. So a lot of the choices I’ve made were about money, and not being ashamed of my need for money. Which again, I think is more working class. All of that is part of what’s rebranding poetry right now: the insistence that we can do a lot of different things is the sign of the poet. Language, poetry, conceptualism, all these movements.

Nowadays, there’s definitely a movement that is more akin to blue-collar sensibilities, in that it’s DIY. Build your brand, and your product is your artistry.

Exactly, because the working class craft is to survive. At all costs. Put bread on the table, put gas in my car, put cigarettes in my pocket. Whatever it is that’s driving you, you’ve got to get that. Look at Michelle Tea. She’s just an example of a working class artist, you know, and I think we’ve influenced each other forever.

Totally. It seems as if people are building their own educations. Past a degree, there’s a whole other worldly education you have to build yourself. And chances are, if you’re resourceful, you’ll probably do better.

As a reader, I’ve seen some consistencies, thematically, in your work–dogs show up on occasion, bars as a setting. Aesthetically, you write in tall columns over the collection. What incremental formal changes have you seen in your work through this collection?

There’s a kind of leaping I’ve become bolder with. I worry less about whether things are clear, or whether this pile of things articulate anything to you. I worry less about the reader in a way. Maybe there’s a way in which it’s more contemplative too. My writing is much more of a tragic pastiche than it was.

When I was a younger writer, a newer writer, I think I wanted to make sure you understood what I was saying. Now I think I have a whole lot less regard for clarity. I feel like I discovered that when you veer away from feeling, you can come back to it with a heavier whack. That really interests me, for work to be really emotional, for that to be the materiality of it.

I agree. I say that with my own writing too. It’s like, you know what? I’m really just interested in having a place to kick the door in, because you can’t do that in everyday life.

Yes. That’s beautiful. That’s exactly it.