Mike Albo: On Sperm and Its Uses, Spirituality, and Learning to Feel

Author: Theodore Kerr

April 23, 2016

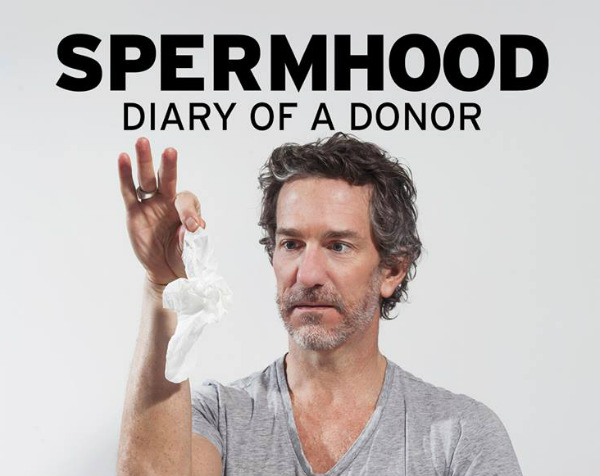

In Spermhood (2015, Amazon) and its upcoming stage production at Dixon Place in New York City (May 13-28th), Mike Albo explores what it means to be a gay man entering into the world of queer parenting. What is to be both gay, queer, and a parent?

He is not alone in his curiosity. In 2012, Cory Silverberg’s book What Makes a Baby? was released, followed three years later by Sex Is A Funny Word. Both books help people parent with a queer lens, providing a way to explain sex, gender, and the body in non-patriarchal, non-binary ways. Earlier this year Staceyann Chin received rave reviews for her play MotherStruck that explored the personal and systemic hurdles she faced having a child as a self described “lesbian widow.” A few months earlier Sebastián Silva’s Nasty Baby was released, a film about a single woman and two gay men trying to get pregnant. At one point the film echoed Gregg Araki’s 1993 film Totally Fucked Up, where lesbian couple Michelle and Tricia throw a party asking their gay friends to donate sperm so that they can have a baby–a reminder that queer parenthood is nothing new and not merely a reaction to the same sex marriage victory.

To this burgeoning canon, Albo adds the unique perspective of a gay man donating to a lesbian couple who happen to be his friends. Central to his journey are the questions: What is it to be the giver? What are his rights and responsibilities? What role does he want to play in baby’s life? Answering these questions leads Albo to consider the homophobia at the donation clinic; the role HIV/AIDS continues to play in his sexuality; and how spirituality fits into his life. What could be just a fun romp toward non-attachment parenting is instead a moving meditation on interconnectivity, establishing ethics, and an insider’s look at what it takes to create a queer family in a straight world.

At a joint reading with Brontez Purnell in November, Albo discussed how Spermhood is a sequel of sorts to his first book, Hornito (2001, Harper Perennial). In structure, they blur the line between memoir and fiction with both putting you in the mind of “Mike Albo,” a gay man trying to find himself amid all the wonder and pressure of being in New York City. In Spermhood, as in Hornito, Albo is still looking for love and meaning, but as he has matured his understanding of these words has changed.

In the interview below, Albo speaks with Theodore Kerr about publishing, spirituality, and how Spermhood will make the leap from Kindle Single to a one-man show at Dixon Place, May 2016.

How did Spermhood come to be?

Well, about four years ago my friends (“Caroline and Pat” in the ebook) asked me to be a donor for them. It was such a wild, weird, emotional journey—one of those times as a writer when you are in the middle of an experience and you kind of have a feeling you will be putting pen to paper later. “Caroline” is a writer too, and she plans on writing about our adventure as well. After the process of donation I spoke with David Blum, the editor of Amazon Kindle Singles, who published The Junket, (2011, Amazon) and he agreed there would be interest because no one ever talks about pregnancy from the donor’s perspective.

Why publish it as a single?

As I writer I usually disregard the idea that people need distance from an experience to write about it. But in this case I needed, paradoxically, both distance, and to get the story out quickly, while I was still feeling its urgency. Maybe Spermhood could have been great as a book, but the process of a book is long. In writing The Junket I learned 70 to 80 pages is sort of the sweet spot for a single, which seemed like the amount of space I needed to tell this story. And the turnaround is fast. I started the book in the spring, and by the end of summer I was editing it for publication.

Do you need to know your work is going to be read in order to write?

Yes. Hornito began as stories I was sharing on stage. My agent at the time said it should be a book. That changed things for me. It helped me deal with the low self-esteem I have as a writer, and got me to set some deadlines, which for me means someone in the world is waiting for your work, which signals to my brain: your voice matters.

We are going to get back to that, but first I want to know, what is it like to write a story that intimately concerns other people, like two moms and a baby?

I had to really think through it. With The Junket I fictionalized things in cheeky ways to be protective of some individuals, but then also I created a lot of fake names to satirize and criticize the media. Spermhood is different. There are parameters. In my contract as a donor it is stated that I can’t write about the child. So going into the project I knew I was going to write about everything that leads up to the baby, but leave the baby alone. And it wasn’t until two weeks before publication that I changed the moms’ real names and used Pat and Caroline. In talking it over with the Momz (that’s what I call them) they were like, yea, that might be good because eventually when our kid reads this there will be that layer of fiction that is appropriate.

Other than that, I knew it was not going to be their story. It is really the story of a gay guy and his cum and everything he thinks about and what cum means to him. It was hard and I was surprised at all this shit—wait, that is gross—I mean, all this emotional stuff that came out.

Like what?

All the AIDS panic stuff, and beyond. I have long walked this city as a sexually active gay assuming I may have STDs in a calm, back burner sort of way. But when you are putting your sperm in a lesbian, who is a close friend, that changes things. No matter how many times I got tested there was always that fear, which goes back to when I was 17 and thought I was going to get AIDS from kissing. It’s all right there in my diaries.

How long have you been keeping diaries?

Since 5th grade, and I have kept them all.

You journal every day?

Oh no. I was consistent from 5th grade to when I was 13, and then I stopped, and eventually started again. In adulthood, they have taken on a blurred form. The work and the ideas have all become the same book…

…And then—as we see in Hornito—parts of the diary make it to publication, which is interesting because with something like Spermhood, the diary goes digital.

The whole digital thing is something I am still trying to wrap my head around. It brings up larger issues around publishing I can get bitter about, like how much they don’t care about gay men.

What do you mean?

I got lost after Hornito and Underminer, which were at major publishers. I was knocking at their door when I was ready to write again and no one was answering. So much has changed since 2005. It has become this two-sided thing: There is independent publishing, and then there is “Book” publishing, which does celebrity memoirs and big fat books. Some great lit gets through that world, but I see more of a division than ever before.

Why do you think they don’t care about gay men?

Because we don’t make money. Because we have sex up the butt and that is not marketable to them. I think it is that simple.

I hear a lot about lesbian erasure but not gay erasure. Is my internalized homophobia contributing to it? I put my homosexuality on the back burner because often short-sighted and exclusionary activism is done in the name of gay. I was one of the people who never watched Looking but decided I hated it.

It’s almost like a spinning wheel of bad energy, right? You have the gay men being overly critical and sensitive about themselves, and then there are the people at HBO who did not give Looking a chance. It is a rating and marketing game. Who is sharing this on FB? Is there a “21 ways to be like Hanna Horvath” type-article happening? The thinking is: If you are not getting your chatter in the chatterverse then you don’t deserve to be produced.

So, while I may bemoan the lack of good gay literature, by participating in gay erasure I am hurting the chances of the next Hornito getting published?

I really think the only reason Hornito was published was because way back in 1999 I was riding the tail end of a brief “Gay guys are funny!” trend that happened when David Sedaris published Barrel Fever. I wonder if it would be published now, with its barefaced sexuality. Then again, I am happy that Isaac Oliver’s funny but still poignant book Intimacy Idiot has come out, and of course Brontez’s book which is so sexual in a great way.

So how do you see yourself in all this? At a recent reading with Brontez, you spoke about how you have gravitated towards queer, something you had not anticipated. Gay has become so boring you said. Now you part of queering parenthood, which has its own related gay and queer politics.

Early on, “Caroline” said that she never wanted a traditional family. She wants a queer family. And it is really her skill and determination that made all this happen. We did queer it. It is not easy for this to happen the way we did it. Fresh insemination without fucking in a clinic or elsewhere between a gay man and a lesbian is not easy.

I spoke with a guy from California Cryobank, a premier sperm bank, and I told him what we had done, how we had subverted the need to have the sperm quarantined for 6 months to smoke out the “critters,” and he was like, “You did what?!” He was shocked we got away with it.

Do you think that the clinic staff is on “homo-alert”?

That is the thing. We were careful. “Pat,” the other mom, did not come with us to the clinics, which was sad because why shouldn’t all the parents be present for every step of the way, and Caroline and I watched how we acted. There is one time, that I write about in the book, that I went off script and Caroline glared at me to get me to straighten up. But at no time did I feel like I was being put through a sexuality test. Instead, it seemed like the whole system is homophobic. Like, there is no gay porn in the donation room. No attempt to even consider that sexuality—or fantasy for that matter—exists on a spectrum. I mean, maybe there are straight guys who likes to see a good gay gang bang?

The lack of imagination that two queer people could be parents is part of that homophobia.

I think they can imagine lesbians having children and they imagine gay men having children, but I don’t think they imagine a lesbian and a gay man making a baby together.

This is another place where AIDS comes in. Like with the epidemic, queer parenthood brings gay men and lesbians together in a life-affirming and intimate way.

I love that about the Momz, and other lesbian couples I know, that they want gay sperm. They want to continue this gay blood.

It makes me think of Tim Dean’s Unlimited Intimacy: Reflections on the Subculture of Barebacking. As I understand his thesis, he is saying HIV is a way some gay men construct ideas of a blood family. What you and the Momz are doing is a version of that but in a way that could become a Hallmark movie. But I don’t see Chris Meloni’s agent signing him up anytime soon for something like HIV Home for the Holidays.

Well, maybe as a co-production with Treasure Island Media!

Yah, right. Which is one of the ways your book is a joy to read because you work through heady identify creation stuff, straddling some seemingly different worlds. And not in a prescriptive way. You are giving us the life of a gay man in a queer experience within a straight world. This does not come without some internal and external work.

My period of donation occurred during a period of self-discovery. I was realizing that I didn’t understand self-love—I know that sounds corny. For a period of a few years, I started to reassess my sexual habits, who I thought I was, who I thought I wanted to be. And it all came out of my penis.

When you talk about any spiritual element of the book you become very self-deprecating or begin to joke more. Not to be an armchair therapist, but I wonder where this deflection comes from.

Oh god, I am so afraid of sounding “holier than thou,” and there is just an embarrassment to it.

What is the “it” that is embarrassing?

To say the word spiritual or spirituality, saying the word faith. I don’t think I could have proudly said I believed in God until last year. Or did I even know that I did? But I do. I am a religious person. I did not grow up that way. I found it on my own, and often I do not feel worthy of saying it.

Is that related to the way gay men are represented or not represented in culture?

Oh, yah. Do you know about Body Electric? It’s a workshop attended by a lot of gay men to help them connect better with their erotic energy. It is a mix of group exercise, spirituality, and touch. After I interviewed the founder Joseph Kramer a few years ago for a story I did for OUT, I walked away thinking that a statue should be erected for him. He brought gay sex through a really dark time. I remember him talking about gay sexuality and saying the big thing gay men have to deal with is shame. I wrote it down, I walked away thinking about the word: shame. But I couldn’t feel it yet. I was still cut off. This is how I feel a lot of media representation of gay men is: cut off, flat.

You make me think of both Audre Lorde’s essay, “The Uses of the Erotic,” in which she explores the difference between the pornographic and the erotic, and the work of Eric Rofes, who was in many ways the founder of the modern gay men’s health movement in the US. He saw how AIDS was often distracting gay men from thinking about their health holistically. Everyone was focused on not getting a virus, they were neglecting other parts of themselves.

He was right. I worry that there will be a lot of suicides down the road if gay men don’t start addressing their spiritual health. One of the things I learned from Body Electric is that we need connection. And that can be hard to find. If we don’t have community, we hit a brick wall and no one is there to pick us up. We have to make sure we don’t go dead inside.

How does this way of thinking impact your writing?

I don’t know how Marilyn Robinson wrote her first book and understood the soul sits in a body. It has taken me a long time to understand that we are souls in physical bodies having human experiences.

Did homophobia impact your inability to know that?

For sure. There were natural moments of grace when I was a child that were shut down by being called a fag in school and all that stuff, and then AIDS happened and that shut it down even further.

Did it ever do the opposite? For some people AIDS made them spiritual.

I hear you. Many of my friends who were in the thick of the AIDS epidemic in the late 80s have come through it gaining incredible wisdom. They’ve been through it. My experience was a bit different. AIDS education was at its heights in 1989 in DC. The minute I came out as a 19-year-old using fake ID there were condoms everywhere. People even just 6 months older than me had a different experience.

I’m interested in how when we were born impacts how we understand HIV/AIDS, specifically I think a lot about the period between 1996 and 2008 which I call “the second silence,” when after so much discussion around HIV thanks to activists, there was hardly any until the last few years when we began to see a proliferation of media about the early responses to the virus. So many of us grew up thinking about AIDS in our own silos, making up facts and meaning on our own based on the last information available. That is why when Charlie Sheen can come out so much of the conversation seemed so regressive. Because it was. When it comes to HIV, we have a hard time looking at the present or in the future.

There is this nostalgia for the rage we see in something like How to Survive A Plague. And the time period when I came out, and joined ACT UP and Queer Nation. There was anger and the guys were hot. Kiss Ins were something I definitely wanted to participate in! And I remember going to parties, meeting guys living with HIV that had gone from being sick to being healthy and happy. Me and my friend, who was also negative, talked a lot about serodiscordant sex. Thinking back, it’s funny how I have the same sexual rules I did when I was 17—nothing without a condom, blow jobs, no ejaculation in the mouth.

And these rules begin to form our sexual ethics, which bring us back to faith and your book…

Yeah, that is one thing I fictionalized. In the book, I am discovering how to feel things in my body and if I am honest, the discovery process started well before donation. It began a few years ago with my understanding that thoughts are thought forms. This was a huge moment for me.

Why was it important to include?

To tell the story of someone who understands they have been living under fear, that person needs to understand that thoughts are not real and that thoughts are thought forms. He can’t understand where “fear” is in his body until he knows this.

In the course of Spermhood, I am trying to feel things in my body, which is hard to do. When someone says something like, where do you feel that, or what does that feel like, I have a really hard time answering. And I have been doing yoga since I was 23. But I get it. It is a training. The more you explore, the more you understand where things are in your body.

I touch on this in the book, but maybe it gets glossed over. It was this weirdly watershed moment while waiting for this guy I call “Bad News Bear” to come over [to my place] for a hookup. I was feeling a nervous thrill and I decided, I am going to feel this. I asked myself, what does this nervous thrill recall, and I realized it was the same feeling I had walking the halls in 7th grade, afraid someone was going to throw something at me. I don’t think I could have understood this if I hadn’t started down a spiritual path. Does that make sense?

Yeah, of course. Talking to you it seems that a theme of your practice centers around the relationship between the body and the spirit, and times when they get cut off from each other. I see that in terms of your writing but also your spiritual journey.

I was listening to a podcast the other day where the host said that worrying is a way of not feeling anxiety and I realize I spin stories to not feel anxiety. What would it be like to feel it? Feeling is hard!

That is why intimacy is hilarious. It is you feeling you and you feeling with someone else! It is hard to keep track of all these things.

This is where diaries come in handy. Those are honest words on a page. The scene where I have to tell “Caroline” that I can’t keep trying beyond two more months was something that I wrote down in my journal, at least in a vague way. And I am glad that I did. It serves as a reminder of when that happened and that I felt that way. Reading through my diaries I can’t believe some of the stuff I wrote, like how often I don’t like myself.

How do you know how much is just for you and how much of the self-reflection needs to make it to the page?

It is hard, and it includes a bit of a comedic dance. I am working on a stage version of Spermhood for a show at Dixon Place in May with David Schweizer directing, and when he read an early draft he said, enough with some of this: we all know you have no money.

So what is on the page is pared down.

There are oceans more….