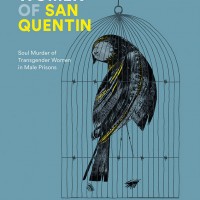

‘The Women of San Quentin: Soul Murder of Transgender Women in Male Prisons’ by Kristin Lyseggen

Author: Mitch Kellaway

December 21, 2015

America, it seems, is just beginning to wake up to the atrocities committed against transgender women held in men’s prisons. Whereas a decade ago, stories of women being repeatedly raped, assaulted by both staff and inmates, held excessively in solitary confinement, and denied even the barest human dignities allowed to male inmates, would not conceivably make headlines; this year alone saw a leap in coverage, culminating in the New York Times’ following the case of Georgia trans woman Ashley Diamond, who opened up about being held in “sexual slavery” in several men’s prisons and denied her hormone treatment against Georgia state policy.

Despite this improvement–which really only captures the smallest tip of the iceberg of the inconceivable amount of abuse that transpires daily–the cold objectivity of reporting, as well as the handful of research studies that have been conducted, does little to capture the warm voices and faces of the women themselves, their resilience, or their complex lives, before and after prison, living in communities and families. That’s where a book like Kristin Lyseggen’s first-of-its-kind The Women of San Quentin: Soul Murder of Transgender Women in Male Prisons makes a significant intervention.

The book, a detail-rich volume filled with photographs and letters written by nine trans women held in American men’s prisons (including Ashley Diamond), is a much-needed contribution to the field of trans-related nonfiction, which tends to focus on either memoir or research. This book spans genres, from photo book to diary to journalism to including some of the women’s poetry, suggesting that an issue as multifaceted as the treatment of trans female prisoners cannot be bound to one way of storytelling. Lyseggen, a non-trans journalist and activist who spent several years corresponding with the nine women included, has done an exquisite job of molding it all into a coherent, balanced, eye-opening collection that builds momentum as it progresses. I found myself easily engrossed, reading most of the book in one six-hour stretch, with tears in my eyes–the latter a rare occurrence inspired only once before by The Women of San Quentin’s closest literary peer, the similarly genre-busting cookbook/memoir of former trans female prisoner Cayenne Doroshow, Cooking in Heels. I recommend reading these two books back-to-back.

Most notable is how The Women of San Quentin rings with emotion through individualistic and respectful portrayals, a key in bringing about the sea-change in hearts and minds needed to ask ourselves what shifts in our perception need to be made to keep women out of men’s prisons (and to ultimately do away with a carceral state that criminalizes race and gender, and in which no prisoners are truly safe from violence). The book pushes its reader painfully to ask: What compromises does a person need to make in order to no longer see or care for the lives and dignity of transgender women deemed “criminals”? Why do we tacitly accept abuse as part of a supposedly “rehabilitative” penalty system? Lyseggen’s strategy is to make sure that we never lose sight of her subjects’ humanity — despite transphobic or racist programming we have received from society and despite whatever circumstances led the women to imprisonment (which were often, but not always, non-violent survival crimes).

The stories of how Janetta, Grace, Ashley, Donna, Shiloh, Tanesh, Jennifer, Jazzie, and Daniella were policed, became imprisoned, and their treatment while incarcerated is valuable information for researchers and activists to use strategize. This practicality is balanced with the book’s literary thrust, offering impact beyond policy, particularly in moments that move from a feeling of data-gathering into interpersonal tension and redemption. There are beautiful images of these women as beloved family members, friends, and community members–something often missed in news reports. Some of the book’s depth also emerges from Lyseggen’s self-interrogations as a white non-trans ally, such as when she’s out at a bar with Grace experiencing unfamiliar harassment or when she’s at the gathering of the World Professional Association for Transgender Health, sitting with black trans women who cannot afford travel or lodging yet are simultaneously asked to educate in Thailand among mostly white, middle-class peers.

There’s also Lyseggen’s honest grappling with whether to include the voices of a women like Donna, who committed incredibly violent crimes as part of a white supremacist gang–what does it mean to critique her treatment in a men’s prison and denial of her transition-related healthcare, even while being deeply uncomfortable with what brought her there? And there’s Lyseggen’s willingness to break up the easily never-ending litany of abuses with complexifying moments where the women either enjoy aspects of prison (such as Shiloh, who loves her roommate Kent) or unexpectedly do not face violence from male prisoners, and instead fear being out on the streets more. The realities and compromises of living in a carceral state are messy and uncomfortable, and Lyseggen succeeds in making us feel it. The book is strongest where it moves away from easy answers.

Demanding multiple readings to uncover its many layers, The Women of San Quentin emerges as one of those rare gems: a compassionate, uncompromising examination of violence that emerges from the voices of survivors themselves, and can therefore be poised to inform meaningful change if we take notice. The more that such thoroughly researched and well-crafted resources exist, the harder it is for us to plausibly deny that the treatment of trans female prisoners demands our attention and resistance. My hat’s off to Lyseggen, who was willing to use her own resources and privileges–personal time, skills, access to space, and money — to create something that the prisons and the odds seemed to refute at every turn. The world needs more art and active allyship like this.

The Women of San Quentin: Soul Murder of Transgender Women in Male Prisons

By Kristin Lyseggen

SFINX Publishing

Hardcover, 9780985624422, 320 pp.

September 2015