“Bendova Like I Told Ya”: Big Freedia and the Healing Power of Contradiction

Author: Dan Lopez

August 23, 2015

“Straight boys sleep with men. And it’s not down low or bisexuality…. People from the outside are always confused about that, but the thing is, when dealing with all the heavy shit—racism, drugs, and poverty—that we are slammed with here, sometimes we just have to let the minor titles roll off us.”

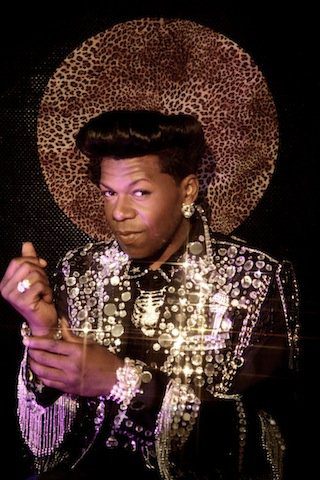

Big Freedia is known for bringing Bounce music and twerking to a worldwide audience (she holds a Guinness World Record for largest simultaneous twerk), but anybody who’s seen her hit reality show will find it difficult to think of Freedia without also thinking of her mom. The late Vera Louise Mason Ross-Johnson took her star turn for two seasons, earning a loyal following thanks to her nuanced mix of ferocity, humility, and heart before ultimately succumbing to cancer. Freedia’s new memoir, God Save the Queen Diva!, is dedicated to this “original Queen Diva.” As on the show, Vera’s presence is palpable on the page, even if it’s not always in the best light. The memoir opens with an altercation between young Freddy Ross (the stage name Freedia was still well in the future) and his stepfather. When Freddy looks to his mom for support she demurs. “Truth is, “ Freedia writes, “she never really told him off like I know my momma could.” The scene ends with Freddy storming out of the house and straight into Pressing Onward church, where Freddy would eventually find his voice as a member of the choir. While perhaps not the most flattering portrayal of Ms. Vera, the anecdote illustrates the dynamic relationship between Freedia and her mom, a relationship steeped in contradiction.

“My momma could be a mess of contradictions,” Freedia writes. “You just had to roll with it and figure out which rule she was running with at the time.” What becomes clear early on in the memoir is Freedia’s ability to successfully inhabit contradictions—whether it’s at home, at church, or in the club. It’s perhaps that ability—so poignantly on display in her relationship with her mom—which has contributed most to Freedia’s mainstream crossover. A lot of the drama in the first two seasons of Queen of Bounce, the reality show on Fuse, centers on the tension between long-standing members of Freedia’s crew resisting changes designed to help elevate Freedia’s career. In one particularly telling moment, Freedia tries to put on a kids show with her old friends, and fellow Bounce artists, Katy Red and Sissy Nobby. Both Katy and Nobby are initially skeptical that Bounce music can be adapted for the grammar school set. In the end, Nobby drops out of the show leaving Freedia and Katy to duet in what is perhaps the show’s most adorable vignette as a park full of tykes twerk. “I think being gay had a lot to do with it,” she tells Lambda, when speaking of her ability to inhabit contradictions. “You have to be able to go to church and school and family events, knowing it’s not OK to be gay. That helped me be able to be in and excel in situations that could be very trying. It definitely helped build character.”

Nobby’s actions notwithstanding, one sees elements of contradiction culture throughout Freedia’s memoir (and, to a lesser extent on the show). It appears to be a structural element of a larger New Orleans milieu that inhabits the intersection of blackness, queerness, and poverty (forces which also inform the Bounce sound Freedia has helped to popularize). “Sexuality in New Orleans isn’t like any other place in the world,” Freedia writes. “Straight boys sleep with men. And it’s not down low or bisexuality…. People from the outside are always confused about that, but the thing is, when dealing with all the heavy shit—racism, drugs, and poverty—that we are slammed with here, sometimes we just have to let the minor titles roll off us.” Ease with contradiction, then, would appear to be a kind of puckish response to systemic disenfranchisement. And while decoupling sexuality from sex, for instance, may initially seem anathema to a broader queer cultural legacy that has largely been structured by insisting on binaries, Freedia’s ease with the contradiction of straight boys who sleep with men offers a way of forging alliances within a construct that seeks to suppress the ability of subjects to build coalitions of power. In that way, it’s not unlike camp. Camp is, after all, simultaneously a bulwark and pillar of a culture under siege. Maybe contradiction is simply the regional flavor of that resistance—something befitting a city that since Katrina has existed in the public imagination with one foot firmly planted in both destruction and rebirth.

Nobby’s actions notwithstanding, one sees elements of contradiction culture throughout Freedia’s memoir (and, to a lesser extent on the show). It appears to be a structural element of a larger New Orleans milieu that inhabits the intersection of blackness, queerness, and poverty (forces which also inform the Bounce sound Freedia has helped to popularize). “Sexuality in New Orleans isn’t like any other place in the world,” Freedia writes. “Straight boys sleep with men. And it’s not down low or bisexuality…. People from the outside are always confused about that, but the thing is, when dealing with all the heavy shit—racism, drugs, and poverty—that we are slammed with here, sometimes we just have to let the minor titles roll off us.” Ease with contradiction, then, would appear to be a kind of puckish response to systemic disenfranchisement. And while decoupling sexuality from sex, for instance, may initially seem anathema to a broader queer cultural legacy that has largely been structured by insisting on binaries, Freedia’s ease with the contradiction of straight boys who sleep with men offers a way of forging alliances within a construct that seeks to suppress the ability of subjects to build coalitions of power. In that way, it’s not unlike camp. Camp is, after all, simultaneously a bulwark and pillar of a culture under siege. Maybe contradiction is simply the regional flavor of that resistance—something befitting a city that since Katrina has existed in the public imagination with one foot firmly planted in both destruction and rebirth.

Whether or not contradiction culture operates in the Big Easy as a variant of camp is up for debate, but at least for Freedia (who answers to both male and female pronouns) being adroit at navigating contradictions, particularly in regards to gender and sexuality, has played a critical role in building her career, and thus providing an avenue out of poverty for her, her family, and her community. She credits her self-defined sissiness with helping attract young fans. “I’ve come to realize that kids today look at sexuality on a continuum,” Freedia writes. “I think the fact that I’m feminine without being a drag queen or transsexual draws them to me.” We live in a culture where cisgendered black men and transgendered black women bear the cruel brunt of an assault on personal sovereignty while a black man sits in the Oval Office advancing, among other things, the causes of racial, sexual, and gendered liberty. In his book, Between the World and Me, Ta-Nehisi Coates acknowledges the consuming contradiction inherent to black life, instructing his son following the death of Michael Brown, “that this is your country…this is your body, and you must find some way to live within the all of it.” Contradiction is life. Reconciling that reality offers a mechanism by which a citizen can cope with the everyday realities of existence in 21st Century America. Places like New Orleans and artists like Big Freedia are among the vanguard delivering that message to the masses.

Freedia has always found salvation in her music. Bounce may not be the gospel music that she sung at Pressing Onward and that held a special draw for Ms. Vera, but it delivers a powerful message of liberation all the same. When Freedia rapid fire chants “azz everywhere, azz everywhere / bendova like I told ya” over a blaring Triggerman beat to a club full of diverse revelers she’s talking about liberating the booty and the mind. That’s a message that can go a long way towards mending our deep racial wounds. “Bounce is for everyone,” Freedia tells Lambda. “Its for young, old, black and white. It’s really about letting loose and healing and we all need that.”

God Save the Queen Diva!

By Big Freedia and Nicole Bain

Gallery Books

Hardcover, 9781501101243, 272 pp.

July 2015