‘Erebus’ by Jane Summer and ‘Fanny Says’ by Nickole Brown

Author: Julie R. Enszer

May 3, 2015

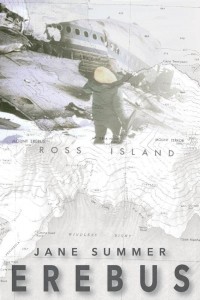

Two recent collections express documentary impulses in contemporary poetry. Jane Summer’s Erebus assembles the story of a plane crash in Antarctica in 1979, then opens into a deeper meditation on grief, loss, what remains and how to uncover it. In Fanny Says, Nickole Brown creates a biography of her grandmother, Frances Lee Cox, evoking Southern grit and glamour. Both collections mobilize their shared documentary style in different ways to achieve their power.

Erebus is a mountain in Antarctica. It is also site of the deadly crash of an Air New Zealand flight. Summer’s girlfriend was one of the 257 people on the flight; all passengers died. Part book-length meditation on the plane crash, part scrapbook of research seeking to understand the crash, part evocation of New York City in the late ‘70s and Summer’s life as a young woman then, Erebus is haunted. People, images, facts—Summer literally assembles them all. She includes newspaper headlines, dental records, photographs, maps and documents from air traffic control. What emerges is a narrative collage of language, some organized as poems, exploring the story of a single plane crash. The loss of the friend Kay weaves throughout the book. Summer writes:

New Zealand police and mountain

rescue team are flown to Antarctica.In my ignorance my image of the disaster

in the locket of my memoryremains pristine: Kay vanishing

in boundless, eternal Antarctic white.

Erebus gathers power by the layering of information from disparate news sources, from the authors personal circumstances and reflections, and from the gathering and juxtaposition of materials. Erebus is reminiscent of Claudia Rankin’s Citizen and Don’t Let Me Be Lonely. On the contrary, Rankin draws many of her visual and verbal images from popular culture; Summer’s images and documentary montage are drawn from visual languages of travel, air traffic and personal family narratives.

Brown’s Fanny Says explores the life of Fanny, a Southern grandmother dispensing advice and judgment in equal measures. Fanny Says delights and dazzles at every turn. In these poems, Brown finds the space and time to explore her own family and the South as an imagined location. In the tradition of great lesbian writers such as Dorothy Allison, Fannie Flagg, June Arnold and Rita Mae Brown, Nickole Brown spins a yarn that is at once fantastical and believable, one that leaves us, as readers, yearning for more.

Brown slips seamlessly among multiple voices in Fanny Says—Fanny’s voice, her voice, the voice of family members, and a collective voice of the south calling its children back into its tradition. While Fanny Says is a biography of Brown’s grandmother, it also feels like autobiography, memoir and tall tale all mixed together. Brown captures the voice of Fanny through a series of poems interwoven throughout the collection titled “Fanny Linguistics.” In these poems, she interrogates language with such a keen eye and such an exacting ear that I simply marveled at her perspicacity. Many other poems begin “Fanny Says” and offer a modern-day etiquette guide to readers with a blend of both earnestness and irony. Ultimately, one of the most striking aspects of Fanny Says is how deftly Brown presents binaries as paradoxes: Southern femininity with Southern masculinity, Southern hospitality with Southern cruelty, Southern politeness with Southern plain speech. In the end, I was as charmed by these poems as I was provoked, and that is an extraordinary combination.

What is striking about both Erebus and Fanny Says is how each poet locates lesbianism in the nautilus of these narratives. Lesbianism never reaches the center chamber yet dwells in the outer parts of the shell. Never announced in the pearly exterior, it lives within to be discovered as a secret delight. Fanny never seems to quite make peace with Nickole’s lesbianism, but she is a practical woman, so it never seems to bother her, either. In one of the epigraphs, Fanny tells her granddaughter, “You didn’t have time for a man. You don’t need no husband. You need to be doing what you worked so hard all these years to do. You need to write yourself a book.” Similarly, the fact that the lost friend is a lesbian seems almost incidental in Summer’s Erebus. For the past forty years, the gay and lesbian community has been telling the narrative that being such is a regular, normal, even incidental part of our lives. This narrative has taken hold. The fact of lesbianism is thus incidental in both of these books.

Yet, lesbianism is also central to both of these collections—if not narratively, then at least aesthetically. Brown could only render the view of her grandmother—the Southern woman driving the big white Cadillac, sitting in the round white wicker chair—through her lesbian eye, through the eye of a woman with both a particular intimacy and a particular distance; a woman who, like Dorothy Allison, could cast her eye upon a Southern woman and feel love, affection and even desire, and then render the character real, honest and informed yet unspoiled by Southern mythos.

Similarly, Summer’s decades-long obsession with this plane crash—evident in her return to the accident, the obsessive account of what happened, the detailed examination of the facts, and the creation of a bond with a person and an event across years—seems unique to a lesbian sensibility. Perhaps lesbian aesthetics include devotion to making a tragedy into art, to making the tragic apprehensible to others outside its scope. The icy world of Antarctica has been a fertile space for a number of other contemporary writers: Lucy Jane Bledsoe’s The Big Bang Symphony is set there; as is Gretchen Legler’s creative nonfiction narrative On the Ice, her account of time spent at McMurdo Station; and Elizabeth Bradfield’s Approaching Ice, a collection of poems about the exploration of Antarctica. Certainly, grant programs supporting artists’ travel to McMurdo have contributed to this sub-genre of lesbian literature, but exploration of extreme spaces and concern with the natural world, particularly at this moment of increasingly visible evidence of catastrophic climate change, all emerge as important aesthetic gestures that may relate to lesbianism—as identity, as material practice and as imagined community.

In Erebus and Fanny Says, Summer and Brown respectively gather language and images from a world much greater than their individual selves. Neither engage in the confessional or personal tendencies found in other strains of modern poetry. Rather, they gather and document material and stories to construct narrative. Further, although the narrative impulse may drive storytelling in both collections, both books—and their authors—insist on meandering as the primary mode of movement. Both are rich and complex poetry collections that will delight readers. Brown delivers poetic mastery with extraordinary craft and control of language, images, line and diction; and Summer creates an expansive assembled text in which poetry tells stories of large-scale human tragedies. Both are exciting contemporary poetic engagements.

Erebus

By Jane Summer

Sibling Rivalry Press

Paperback, 9781937420901, 186 pp.

March 2015

Fanny Says: Poems

By Nickole Brown

BOA Editions

Paperback, 9781938160578, 136 pp.

Paperback, 9781938160578, 136 pp

April 2015