Editing Huey P. Newton: Reflections on The Black Panther Party

Author: Donald Weise

September 21, 2013

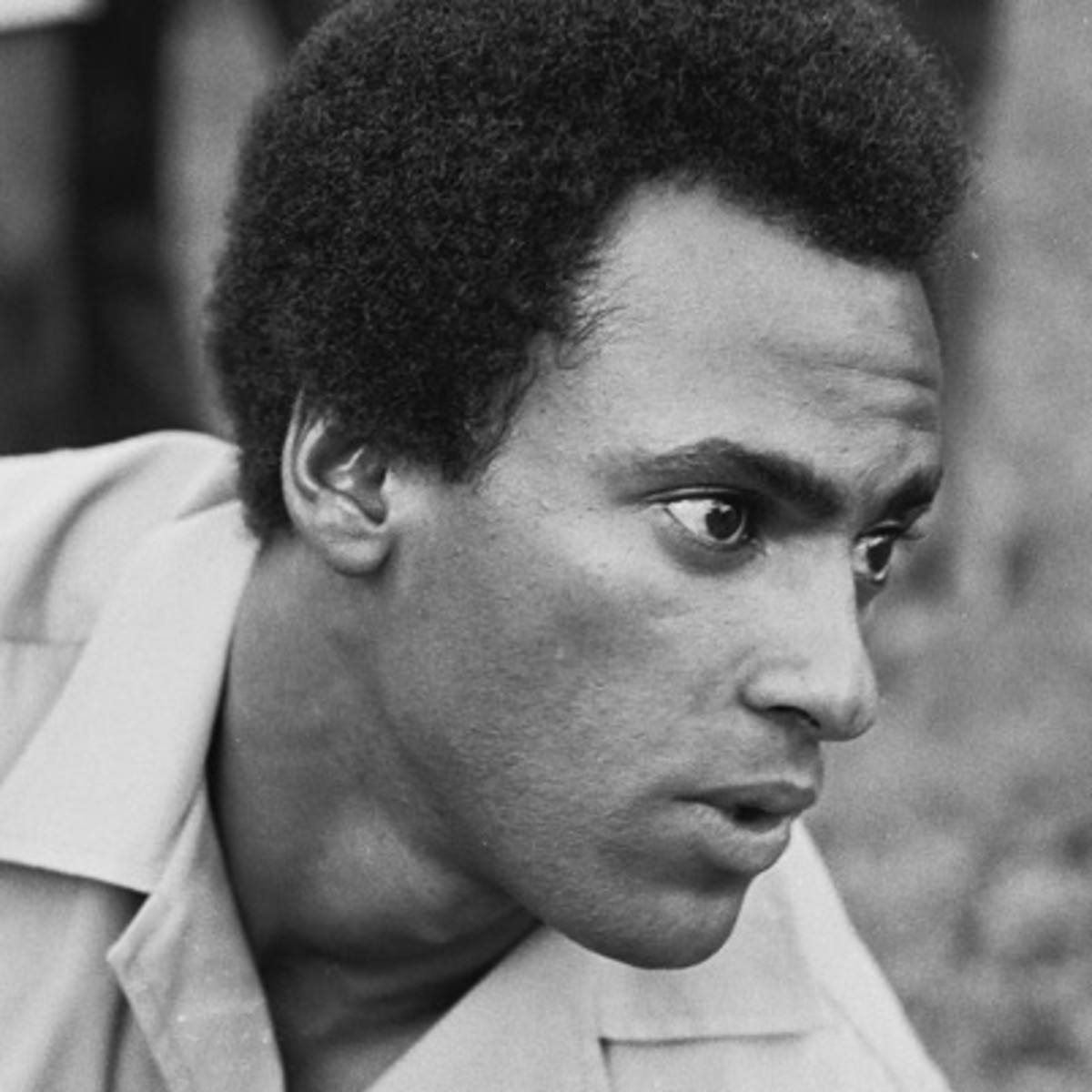

“The racist dog policemen must withdraw from our communities, cease their wanton murder and brutality and torture of black people, or face the wrath of the armed people.” That’s Huey P. Newton. He was cofounder and leader of the Black Panther Party, the largest black liberation movement in US history. You can tell the quote comes early in Party history because Huey’s fiery rhetoric owes an obvious debt to Malcolm X, the spiritual father of the Party when it was established in 1966. But as Huey grew intellectually and became a world-renowned black liberation leader himself—the biggest, in fact, in his moment in time—that rhetorical influence became less apparent, the language still provocative but more academic, more sophisticated, less outright inflammatory.

Huey was the first person I ever edited. It’s about the most unlikely beginning for a gay book editor that I can think of, but the experience helped shape my work. Among other things it gave me a new appreciation for language. I have a special fondness for Huey’s early rhetoric—he says exactly what he means in the most unambiguous, if admittedly colorful, language imaginable. Black people with guns, if provoked, will shoot and presumably kill policemen in self-defense. I sometimes think I’ve carried this influence of and preference for direct speaking into my work as an editor, even if unconsciously, when I ask writers to tell me more clearly what they mean. Forget the lyrical turns, if they cloud the message or storytelling. In Huey’s case, his colorful language is essential to the message, and it’s hard to imagine him expressing himself in a less incendiary way. After all, African-Americans around that time were rioting in cities across the nation.

Although I don’t like guns, I see this quote about “the wrath of the armed people” every day. It’s captioned in a framed lithograph of Huey that hangs over my desk at home. In it, he sits famously in a wicker chair, a spear in one hand, a rifle in the other. It’s one of the most iconic images from the 1960s protest era, and I like to think that Huey, who died in 1989 before I could ever meet him, at least figuratively watches over my work.

The poster was a gift from David Hilliard, one of the founding members of the Black Panthers and their first chief of staff. David became my mentor in 1993 when I met him in Oakland, California, where the Party originated the year I was born. The poster was a gesture of appreciation for serving unofficially as his assistant for ten years. Under the auspices of the Huey P. Newton Foundation, a nonprofit organization dedicated to preserving the Party’s legacy, David and I did everything from giving away free books at public housing complexes and organizing a Black Panther history tour to teaching a college course on the Party and writing the blueprint for the Black Panther Party curriculum in Oakland’s public schools.

You could say that David was giving me gifts from the beginning, in the form of political teachings I couldn’t have gotten through books. I learned, for example, the real-world differences between radical and revolutionary, as well as the true meaning of well-worn expressions such as “all power to the people.” Through David I also came to see that feeding poor school children was as revolutionary as standing down the police. In short, what I’d learned in books about the Black Panthers (and political protest in general) was only the start of a political education. It took going with David into poor neighborhoods, black churches, public schools that were still racially segregated in the 1990s, and meeting former Party members—ones I’d read about and ones I hadn’t— to come to a more profound understanding. A personal understanding, if you will. Because for anyone to talk or write about the Party meant talking or writing about David and his old comrades.

When I first met David I’d just started in publishing. I’d gone to an author appearance for his new Black Panther photo book, and when I introduced myself and said that I worked with books, he asked if I could help him find a publisher to reissue Huey’s long out of print book-length conversation with psychologist Erik Erikson, In Search of Common Ground. At that time the Black Panthers were the hottest they’d been since the Party’s demise around 1980. David had published an autobiography, This Side of Glory, the year before, as had former Black Panther Chairman Elaine Brown with A Taste of Power. There was also the feature-length movie Panther in theaters about this time, and two of Huey’s books—his autobiography, Revolutionary Suicide, and book of essays, To Die for the People, edited by Toni Morrison—were released in new editions. As it turned out, I wasn’t able to find a publisher for In Search of Common Ground. Instead David invited me to read Huey’s unpublished writings with an eye towards a new book.

For someone who wasn’t principally a writer, Huey had a lot of unpublished material. From the first few essays it was clear that he’d come a long way from the rhetoric of “the racist dog policemen.” These were writings from the 1970s and 80s, and they were often intellectually dense, philosophical pieces written in later years, after Huey had earned a PhD from the University of Santa Cruz in the History of Consciousness. There were also hours of audio recordings no one but David had heard, long conversations that, I was told, went late into the night because once Huey got started there was no stopping him. Some of the material was over my head, but listening to Huey, even when he spoke at length about Nietzsche and Kant, was fascinating because he was so clearly passionate about ideas that you could almost see him, animated, speaking to the listener, whoever he was. But months later, David and I decided the project would be stronger if it were more accessible, a collection of Huey’s published and unpublished writings gathered together for the first time. Years later, after a long delay with a publisher that finally went out of business, The Huey P. Newton Reader was published by Seven Stories Press in 2003.

In the meantime, I’d become David’s right hand person in the day-to-day operations of the Huey P. Newton Foundation, of which he served as Executive Director. I can’t recall how exactly I went to work with him or when—I can tell you he never asked me to serve in that capacity, it just happened—but soon I was going over to his place evenings and weekends to help write letters, articles, book proposals, anything, really. Back then David had more energy than anyone I’d ever known. Although he was my father’s age, he went about his day as if he were mine. He seemed to be everywhere, making appearances, giving talks, sitting on panels, meeting with elected officials, writing editorials, all while running the Foundation. His tireless political commitment was such an example to me that I felt I had to match his stamina by being there for him anytime he needed me. Besides it was a lot of fun.

Even in the months when I was brand new to publishing and had not yet met David, books were political for me. For example, I started a free new book program with friends that was inspired in part by the Black Panther free grocery program for the poor. I’d gotten the idea from educator Jonathan Kozol, who said publishers should donate overstock to poor and working-class communities. The company I worked for had pallets of books of this nature—titles where more were printed than ever would be sold; biographies, cookbooks, children’s books, novels, histories—and there were enough in our enormous warehouse to fill at least ten empty bookstores. I was given a donation that we then took out to the Lockwood Gardens public housing complex where I knew someone. We put up folding tables on the lawn in front of the community health clinic, set out all the books, and invited residents to take as many books as they could carry. Watching all those people with their free books is still the most beautiful moment I’ve had in twenty years of publishing. After I was given another donation the following month, we went back and set out more books, and then again the month after that, every month, hundreds of books each month, for several years. I’d guess we gave away as many as 10,000 free books. All because Jonathan Kozol suggested the idea, publishers were generous enough to make donations, and the Party showed me a way to pull it off—just bring books to the people and let them choose.

Shortly after I’d met David I invited him to speak at one such gathering, and from then on the program became an extension of the Huey P. Newton Foundation, with the Black Panther logo now printed on our free book fliers. We handed out those fliers all over the city, too—libraries, shops, schools, take-out restaurants, even going door-to-door, which was more “hands-on” than I was used to. One time David drove up in front of an apartment complex in one of the poorest neighborhoods in town. I was no stranger to Oakland’s poor neighborhoods and was alright with the ones I knew, like East Oakland where we gave away free books, but poor neighborhoods that were new to me were another story. A group of five or six black teenage boys was sitting on a truck that was parked on a burned out lawn. David asked me to give them fliers. I looked over at the truck and said apprehensively, “I don’t know, Mr. Hilliard…” Looking straight ahead, he said, as a challenge, “Well, Don, if you’re scared…” Yes, I was afraid—afraid that they’d think I was a cop. What else would they think about a white stranger in a black BMW offering them a Black Panther flier announcing free books? That had to look suspicious. But I did go over to them, handing each guy a flier. As they dutifully took and read them, one kid asked, “So what kinds of books are you giving away?” So much for them thinking I was a cop!

Working with David had no regular or predictable hours—he might, for example, invite you to Christmas then ask you to help write an op-ed piece before dinner, and it would feel rewarding and in no way unusual to be writing an op-ed piece on Christmas as everyone else opened gifts in the next room. Working weekends was a given, including early hours. One Sunday while driving through Berkeley on our way to breakfast, we stopped at a traffic light. Out of the blue David asked, “You want to meet Eldridge Cleaver?” Then he said, pointing to a table at sidewalk café, “There he is.” Cleaver had on a bright green turtleneck sweater and an elaborate white necklace that looked like it was made of animal teeth. I’d never seen—much less been introduced to—him in person before, and even today I can’t say exactly how deep David’s dislike of “El Rage,” as Cleaver was once known, went. What I knew for certain was that Cleaver was infamous and former Party members I’d met detested him. As the Black Panther’s Minister of Information, he was first an enemy of the right then later the left after he broke with Huey in 1973 and became a Republican, born again Christian, and alleged government informant. David continued, “You should go over to him and say, ‘Mr. Cleaver, I’d like to shake your hand.’” I knew he wasn’t serious, because not only did David know that I shared his low opinion of Cleaver but he was aware of his homophobia, including Cleaver’s public attack on James Baldwin for being frustrated, along with many “Negro homosexuals,” because “in their sickness they are unable to have a baby by a white man.” Sitting at that table, Cleaver more than anything just looked old, and it was hard to imagine he once frightened people.

Cleaver’s homophobia wasn’t unique in the Party. I wasn’t there back in the day, so I can’t speak to how widespread it might have been or what it looked like. However, homophobia among the Black Panthers was pronounced enough for the gay French novelist and playwright Jean Genet to object to it vociferously when he came to America in 1969 to speak out in defense of Party leaders Bobby Seale and Ericka Huggins when they were on trial for conspiracy to commit murder in New Haven, Connecticut. Genet protested to David, who was his escort while in the US, and word was sent to Huey in California, who in response issued the following statement in 1970, just one year after the Stonewall Rebellion:

Whatever your personal opinions and your insecurities about homosexuality and women (and I speak of homosexuals and women as oppressed groups), we should try to unite with them in a revolutionary fashion…We must gain security in ourselves and therefore have respect and feelings for all oppressed people…We have not said much about the homosexual at all, but we must relate to the homosexual movement because it is a real thing. And I know through reading, and through my life experience and observations that homosexuals are not given freedom and liberty by anyone in society. They might be the most oppressed people in society… [T]here is nothing to say that a homosexual cannot also be a revolutionary…[M]aybe a homosexual could be the most revolutionary…We should be careful about using those terms that might turn our friends off. The terms “faggot” and “punk” should be deleted from our vocabulary…We should try to form a working coalition with the gay liberation and women’s liberation groups.

I’m unaware of any leader of a non-gay political protest group of that period, much less an organization of the magnitude of the Black Panthers, then at its zenith, coming out so publicly on behalf of the gay rights movement in such outspoken terms. As for my experience with David personally, he was as supportive of me as an openly queer person as any PFLAG parent. In fact, David was great on this count. How you defined your sexuality didn’t matter to him—but your politics did. As he told me any number of times, “When the police come breaking down your door in the middle of the night, you’re not worried about the sexual orientation of your bodyguard.”

But what about gay people in the Black Panther Party? Who were they? I met and spoke over the phone with former Party members who I thought or knew were gay, though whether they were—or were open about it—was another story. The most notable in my experience was David DuBois, son of the iconic (even that word doesn’t do justice) black civil rights leader W.E.B. DuBois and Shirley Graham DuBois, a political powerhouse in her own right. David was a writer who Huey personally invited to edit the Party’s newspaper. Huey knew David was gay, as did others in the Party, but wanted him on the paper anyway, and it was a wise choice. When you look at old issues of The Black Panther today, you can see an important shift towards an international outlook that was very much in step with Huey’s own political evolution at the time towards globalism, or “Intercommunalism” as he called it.

I didn’t have the chance to meet David DuBois in person before he died in 2005, though I once spoke with him by phone about participating in a gay and lesbian literary festival in San Francisco; I wanted him to talk about being a gay man in the Party. Considering I was stranger to him, David was cordial as he listened to my pitch. When I finished he began speaking about his “situation,” which at first I didn’t understand. But after he said it a few times I understood, so when he finally asked, “Do you know what I’m trying to say?” I said, “Yes, you’re gay.” “That’s right,” he said, sounding relieved. I liked him. I asked about his dad, who, among other towering accomplishments, cofounded the NAACP in 1909, and it felt surreal speaking about our fathers; his, a civil rights giant, and mine, a security guard in Sacramento. At least we had being gay in common.

Until now I’ve not spoken publicly about working with David or my involvement with the Foundation or my editorial beginnings as Huey’s editor. Somehow all this has felt too personal, too close to me emotionally and politically, to share. Besides I couldn’t trust that people would relate. When I have mentioned David to gay men, I’ve often been asked if he’s gay—because presumably no black man would work with an openly gay man unless he were too; never mind the historic working relationship between labor leader A. Philip Randolph and gay civil rights trailblazer Bayard Rustin. I’ve also been asked if David and I were romantically involved, a question so crazy that I began speaking, even in private conversations, about my work with him and the Foundation less and less. But after I’d given a talk last month at the annual American Library Association convention about my origins as an editor, I began thinking about my career and the ways in which it is not rooted entirely in LGBT literature—no matter that to everyone else it looks exactly like that, and I can’t blame anyone for drawing this conclusion. Suddenly it felt especially meaningful for me to share this story, if only to show where I come from as a book editor.

When I decided to leave San Francisco and move to New York in 2003, David and his girlfriend, Fredrika, hosted a small farewell dinner in downtown Oakland that was attended by my ex-boyfriend and ex-girlfriend and my ex-boyfriend’s new boyfriend (fairly sophisticated even by San Francisco Bay Area standards). I’d worked with David since 1993 and saying good-bye, I couldn’t help but feel that I’d met him for a reason. I suppose in a nutshell you could say he expanded my consciousness, political and otherwise, over a period when I needed for that to happen, but also over a period when it could in fact happen because I was still young and impressionable. There are some experiences, like going to college or living abroad, that change forever how you look at the world. My time with David is akin to that, only more precious because it’s an experience no one else I know has had. Writing about it now and recalling our time together only underscores that fact. I left California with that poster of Huey in the wicker chair to remember David by. And right now, sitting at my desk, if I turn to my right, there’s Huey still talking about “the racist dog policemen” facing “the wrath of the armed people.” Still watching over me.