Splitting from the Spectrum: Comics and Alternative Sexuality Get Legs of Their Own

Author: Charline Tetiyevsky

July 7, 2013

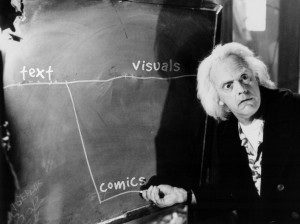

“Comics aren’t text and visuals mushed together any more than my sexuality simply combines homo- and heterosexual tendencies.”

Hi, I’m Charline and I am addicted to contradictions (and nicotine, adrenaline, endorphins, hard cheeses). There’s something inherently exciting about combining two things that seem to make little sense together; that’s partly why I became interested in studying comics. I write a theory on the medium for my comics site the Sunday Syndicate, mainly exploring how text and writing can come together to create an entirely new form of art. Comics aren’t the sum of their two parts, but rather completely new creations that transform the way that visuals and text are used to tell stories. The two elements interact with and change one another, giving comics an identity of their own.

That’s a difficult concept to explain, the fact that combining two ends of one artistic spectrum results in something in its own sphere of existence. It kind of makes me feel like Doc Brown from Back to the Future, like I have to draw a figure on a blackboard. Actually, you know what? Here:

It’s hard to explain to people who haven’t really read comics, but the space in the middle of text and visuals can be more accurately defined as illustration, which is the actual combination of the two. The reason that I put comics on their own plane is that the text and visuals function differently when the text isn’t simply used as a descriptor for the image. When it comes to illustration text is almost incidental in the sense that a caption only contextualizes the image without transforming its meaning. Illustrations clarify already presented material, while comics tell stories unto themselves.

The transformation is an important point, since there’s active thought being given to the way that the two elements of comics are combined. The medium acts in a way that either element could not function alone. There’s something new created here, something that takes the normal relations between text and images and links them in symbiosis to make an active medium that demands the reader constantly consider those two means of storytelling at once.

Sequential art is, as it turns out, quite a complicated medium to explain. The books were treated as purely pulp for ages, partly because of the surge of superhero comics in the mid-20th century but also because it was uncomfortable and difficult to think of the reasons why combining two separate media would result in anything less than a clusterfuck–or, somewhat more kindly, a children’s book. Truly understanding comics requires first understanding the way that text and visuals are transformed when they come to depend upon one another to create a narrative. The mind is forced to learn how to accept limits on its imagination (that is, we’re used to reading and creating our own visuals, or seeing visuals and imagining what is going on) and focus instead on interpretation of what is given. This often results in greater attention being given to meta-narrative, namely to the way that panels transition from one another and what these unspoken spaces in the middle mean. That’s where the imagination really comes in: in the ambiguous transitions from one event to another, the places where you’re given nothing but a small strip of white space.

It all seems to come back to that transition, to the act of considering where one thing becomes another. I’ve had that very issue with my sexuality for as long as I can remember being aware of such desires or interests. I came out as bisexual at 16 but the label always felt uncomfortable and forced,[1] like it didn’t quite get at the specificities of what I was feeling. I liked (and like) both men and women, sure, but I’m not nestled in this comfortable place where gender isn’t an issue. I actively prefer women, but my sexual history doesn’t necessarily match up with such preferences for a number of reasons (e.g. having been closeted and self-loathing for many years, feeling discomfort with what I felt was the “awkwardness” of my specific sexual preferences). And so while I’d usually just give a person my number on the Kinsey Scale (probably somewhere in the 4-5 range)[2] to make matters simpler, I can’t ignore that the scale is classically defined by “behavior” and not by desire.

The scale is flawed, but only because it’s dated in its understanding of sexuality (I mean, obviously, since Kinsey was quantifying sexuality for the first time). Someone can be a 6–exclusively homosexual–and still have never acted upon that for any number of reasons (being closeted and uncomfortable, of course, often leading that list). Does that make them any less homosexual? No. It makes them a normal human, grappling with established social mores and whatever personal mishegas they have going on. We have to admit that humans have the capacity to be very self-destructive, especially when faced with self-awareness regarding something as crucial to an individual as sexuality. And so to define our sexuality by “incidental” or “more than incidental” forays into either homo- or heterosexual relations doesn’t really get at the core of the way that we think about ourselves.

I was never really concerned about labels or justifying my actions when I was younger and I’m sure that if I read this as a sixteen-year-old I would be frustrated with what seems like a call to decode my own inner workings solely for the benefit of others (whether that be an individual or a collective). But I’ve learned two major things since then: first of all, that we have a responsibility to explain to others things that they do not understand, and secondly that pushing yourself to get this explanation is really most immediately beneficial to you. I know that the first point is contentious, but I’m not using it simply in the discussion of sexuality. In order to increase public awareness and understanding of non-standard issues, we have to talk about them openly and honestly. No one is going to change others’ frames of mind if we just shrug and walk away from the confrontation.

Now, I don’t mean to imply that just because you happen to have non-heteronormative sexuality you must talk about it to others. The burden of social change is heavy and I don’t want people to think that they have to stop every bigot they speak with to break down the way they feel and why. But it’s undoubtedly a responsible action, and a brave one, let alone a basic building block to establishing a more conscious society.

This isn’t just the case with sexuality; it’s relevant with anything that the public at large hasn’t been exposed to or spoken to about. I get similarly biased and ignorant responses when I tell people that I work in comics. Many people’s brains tend to shut down when something becomes less than black-and-white, and I find myself having to push to get them to understand that no, comics are not just for kids and yes, they’re a legitimate medium with a growing presence in high art. Comics are still in the sphere of communication (again, that scale capped on one side by text and by visuals on the other) just the way that preferences outside the basic hetero-/bi-/homosexual categories are still in the realm of sexuality. But just because comics and sexuality fall under the umbrella of their respective disciplines (for lack of a better word) doesn’t mean that they sit in the middle of the overarching scale. Comics aren’t text and visuals mushed together any more than my sexuality simply combines homo- and heterosexual tendencies. That sort of simplistic explanation hurts more than social understanding of non-normative objects and interests: it hurts the person who has those interests and preferences by distilling the two into simple mid-points on a line.

My sexuality, like almost everyone else’s, involves a complex set of interactions between desire and action, between homosexual and heterosexual urges, between resistance and acceptance. There’s no word for the way that I feel; “lesbian” seems disingenuous and “bisexual” seems too vague. But pulling myself under the blanket term “queer” does nothing to help my own, still developing, understanding of the way that I feel. It might be a convenient method of explaining to others within the non-hetero community that I am in some sort of indefinable space, but by not coming up with a more complex–and accurate–way of identifying myself I do both myself and the community at large a disservice.

There’s no catchall term for the way that I feel, but even if there were it wouldn’t even remotely do justice to a person’s sexuality the way that a longer explanation (really, even just more than one word) would. The danger of misunderstanding looms large, which is something that I realized when using the term “comics.” Even in that case, where there is one word to describe what I’m talking about, the preconceptions and buried prejudices make the word essentially worthless since it alone doesn’t communicate what I really mean.

When it comes to sexuality such explanations seem daunting, but the more that I speak about my own feelings with my friends and the other wonderfully open-minded people that surround me the more I realize that accuracy isn’t the point in such discussions, at least not in the beginning. The discussion itself is important because it leads to complex thought and personal revelations about elements of ourselves and of external objects that cannot be neatly explained away in a few words. The point of such self-analysis isn’t to get to The Way to Summarize Everything, it’s to work through the intricacies of how you feel so that you realize that there is no way to neatly summarize everything, that the complexities and contradictions of human desires and interests are what make our experiences so unbearably beautiful.

—

[1] I was teased mercilessly as a kid for being a “lesbian” and a “dyke,” and at the time coming out seemed like both an admission and a way to get kids to leave me alone. It was basically going up to a big bully and saying, “Yeah, what of it?”

[2] The Kinsey scale, as I’m sure most of you know, runs from 0 (“exclusively heterosexual behavior”) to 6 (“exclusively homosexual behavior”). In the middle are bits labeled as “incidental homo/heterosexual behavior” and “more than incidental homo/heterosexual behavior” (3, of course, is defined by equal amounts of gay/straight “behavior”).