‘Postage Due’ by Julie Marie Wade

Author: Sarah Sarai

June 13, 2013

A collection of straight-ahead poems is a good thing, but equally good and also refreshing is a poetry collection diverse as a sound financial portfolio, with poems, prose, prose poems, epistles, and postcards revealing versatility and offering preventative action against dread humdrum.

Julie Marie Wade’s Postage Due (White Pine Press) makes use of the mixer-in-er approach to create an autobiographic collection at times rhythmic, at times fragile, and always eventful. She escorts us to and out of the airbrushed suburbia of her conservative childhood in West Seattle.

There are four sections: “Lent” “Pentecost” “Advent” “Epiphany.” I don’t necessarily associate the poems in each section as being apropos to the Christian cycle, but doing so is not a requirement—headings are often more useful to the poet as an organizing principle than they are to the reader who delights in finding meaning where and as she will. So whether or not poems in “Lent” address renunciation and preparation, they unveil the beginning of a life. Literally. “I remember being born” Wade writes in “Aubade”—Postage Due’s first poem. “In Pittsburgh, the men carry heavy lunch boxes; / then there is a sadness to their stoop & swagger / I can’t believe the paradox: heat rises as light falls— / uncanny / Pool cue Mood light Magic eight ball // I remember being born.” The assertion is thrown out like a challenge. It’s a universal beginning to a collection often choosing the precision of the personal to elucidate the greater world.

Complications of gender and sexuality are never far off. “A woman is a grave, my father warned me. // I walk dead before God & men” (from “Arthur Dimmesdale, Alone in the Closet With a Bloody Scourge”). Dimmesdale was the secret lover of Hester “A” Prynne; he’d whip himself in that weird belief that self-hurt helps the soul. At any rate, the love that dare not speak its name is often simply love, and other times, simply lust. Love or lust, straight or gay, it isn’t easy being corporeal. But it’s also a joy, as are love and lust, both of which Wade extols in their lady business permutations, “. . . the grease of thighs at the point where they come together—delta of heat, of fragrant fire.” If only Nathaniel Hawthorne’s characters had been free to romp and celebrate. Wonderful writing.

Of the “prose pieces,” which in our title-mad world of writing could also be considered creative nonfiction or memoir, I was especially struck by “Nocturne for Family Fun Night.” The title sets the scene—a family outing during which things work, an idyll in which kids from school appear “less sinister & more believable as friends.” And there’s a rare, fleeting moment of father-daughter connection.

Because what I wanted more than anything was not to be the only child & not the only one on whom everything was riding for my parents & my grandmother & my aunt who was also godmother—a whole family of fledglings desperate for a swan. And because my father had been a traveling salesman like his father before him . . .

Wade rolls words like they are hoops: “& my selfishness & his submissiveness were no longer under scrutiny the way they were when he became divided by my mother, & since. . .”

The poet’s rhythmic sense and facility are a joy. Her use of ampersands mimes a style of logic I transliterate thusly: & because a & b happened, then c was likely). The ampersand’s sly female squiggle is an expression and amplification of a girl’s twisting reach for something great, or at least more fantastical than is normative. Perhaps influenced by the geography of her West Seattle childhood, West Seattle being sort-of beachy, a sort-of promontory on the Puget Sound, Wade knows to allow the words and rhythms to roll on in her vast paragraphs, as a westerner should.

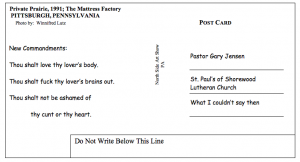

As for the postcards that dot this book, they offer shorthand of what already is a short hand (poetry). Certainly they have quick messages, each a fuck-you conveying an unwritten dispatch: I’m having a great time, glad you’re not here. To wit:

“Extinction of Useless Light” is an ekphrastic response to the Yves Tanguy painting at New York’s MoMA. The stripped-down lines and telegraphed verbal images serve as synthesis of the surrealist painting’s eerie authority, with a hint of “insinuation.”

Slow gradient of gray, ascending.

The unkempt woman ragged in the wind.

Pastiche is just a softer word for paranoia.

The Wolf acquires another county seat.

That wolf rips out my heart, while showing Wade’s hand. It is her inclination to interpret space and uncertainty as harsh and “ragged” without denying the beauty of, say, the slow gradient, even of gray. Reading wolves as rapacious creatures rather than misunderstand and wondrous animals—another fair perception, I suggest they are devouring the public trust everywhere we look, rendering the land as empty as in the painting. I suggest that’s Wade’s intent.

On the issue of the great Mary Tyler Moore, Wade includes letters addressed to Laura Petrie and Mary Richards, two characters famously played by the actress. The letters are, perhaps, a bit disingenuous, referring to Laura Petri’s “capri pants & smile” as if the adult Wade were pretending to be Sandra Dee in a cardigan and saddle shoes, scribbling on her bed. But she’s writing about Mary Tyler Moore, a comedic pioneer and genius from an era when there were fewer comedic women than we have now. Mary Tyler Moore was and is a resistance movement, an embodied struggle against the wife-in-high heels era, a performer who embraces the stifling phenomenon like a cross-dresser belting out a Liza medley, makes it her own—and wicked.

Julie Marie Wade has written a provocative poetic autobiography, which, whether or not it’s true or accurate to fact, is true and accurate to art, sexuality, and life in general, and highly readable.

Postage Due

By Julie Marie Wade

White Pines Press (Marie Alexander Poetry Series)

Paperback, 9781935210443, 108 pp.

April 2013