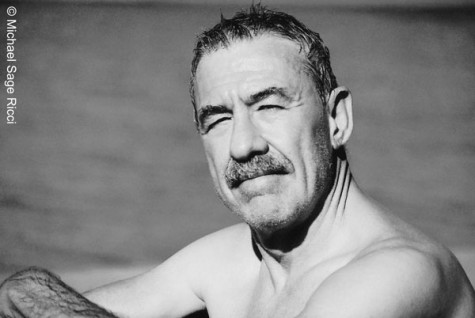

Interview: Tom Spanbauer

Author: Cathy Camper

June 1, 2006

Tom Spanbauer’s books include Faraway Places, The Man Who Fell in Love with the Moon, and In the City of Shy Hunters. Although his books consistently show up on writers’ and readers’ lists of favorite books and best gay fiction, he’s often labeled a cult writer by the literary establishment. I interviewed him this spring about his writing, and his latest book, Now is the Hour.

This book is about bullies: parents, classmates, the Catholic Church, and occasionally even your protagonist Rigby John. What drove you to make this a focus of your book? Do you feel bullying is an element that will always exist in the context of growing up gay?

I think there’s always going to be bullies. It just seems so inherent at that age: you don’t know who you are, you’re not like other kids, it’s so important to be like other kids or to be cool, and of course your body’s grotesque, so you have all this horrible self-opinion. What you need at this time is a good opinion of yourself, but that’s exactly the time you don’t have it. And there’s this bid for power, and “I’m not my father,” and “I’m as strong as my father.” And really the other side of the bully is, he’s terrified. He has learned to, instead of internalize it, externalize it. So he’s got a problem too.

…

In my own life, I was always the mark for the bully. I was a kid standing at the side of the road, waiting for the bus, my hair parted on the left, in my Catholic school uniform with my books, ready to love Jesus and try and turn the other cheek. And you know, every kid on that bus would look at me and go, “There he is, let’s beat the crap out of him!”

…

I think specifically as far as gay people and gay teenagers go, if somehow we can get to them and say, “Yeah, you’re gonna get bullied because you’re queer,” when it’s happening in the lunchroom, that queer boy or girl can go yeah, this is bullying, this is abuse, and there it is. If you can get that message out .

Writers from the Midwest, the south, and the west are often perceived as “regional” by the east coast literary world. Can you talk about where your writing fits in, in writing about gay culture that’s not always urban.

There’s that thing they always say about me, “the cult writer.”The first thing I think of is, “Way to marginalize me.” So I’ve got a bunch of people who love to read me, my books sell, so I must be “cult.” But on the other side, there’s a whole bunch of people who love the book, and so I should just say, “Yeah, cult, that’s cool!” You can look at it negatively or positively. But really, the arrogance of New York sometimes drives me nuts.

…

I don’t think of myself as a western writer, a mountain writer, or an ex-New York writer, or as a queer writer, although all those things fit. I know there are places in me that need investigation. I’m going to these sad, sore places where I feel I need some awareness, and I’m going to go there and investigate them. So I think of myself as someone who’s really involved in his own consciousness in trying to seek out my own homophobia, my own racism, my own gender shit that I have.

All of your books involve a kind of spiritual transformation of the gay male protagonist, often under the guidance of a non-white mentor. Why do you feel this change is so crucial, and why are the catalysts these particular teachers?

In the typical hero myth there’s all levels of hell the hero has to go through to come to an understanding or awareness. That’s inherent in the story. There’s something about the “other” in my stuff that comes up a lot. I was so different from my father, my mother, the Catholic Church, and everybody else. There was a certain point when I started to eroticize the “other,” more than just eroticize, romanticize too. Generally my character is innocent, unaware, and full of all kinds of Christian crap, racism, homophobia. When he does meet the “other,” what happens is, awareness begins.

…

The traditional Native American way of looking at the world is such an antidote to our American way. Everything is alive, we should treat the Earth as a lover, we’re caretakers of the Earth. It’s just so smart. I have a Native American brother, Clyde Hall, he’s a quite famous spiritual person. We became blood brothers in 1968, we cut our wrists, all that. Here we are 38 years later still as close as ever.

Was it difficult to write a book so close to your own life story, and how did you cope with “outing,” as in exposing, people other than yourself?

In a way this book is drawing a circle around myself. I believe that you have to find a place where it’s just you. I have the permission to talk about myself. I can’t think about mother, sister, father, I just have to think about me and how this all came down on me. If it were mean-spirited, or I was trying to show what assholes these people were, I don’t think it would work. Instead, we see very complicated people with lots of layers.

Why did this book take so long to write? While writing a long novel, how do you maintain a consistent voice, over the time it takes to write the thing, and especially confronting life events that change you as a writer?

I don’t think four and a half years is a long time to take on a book, at least for me. For example, I’ve assembled all my African stuff in a little altar, because I want to start writing about Africa. So my process is investigate, investigate, investigate. You got to nose down everything, you got to smell everything, you gotta pick it up, you gotta look at it, you gotta turn it over. That’s just my process. In that process, it takes time. It’s an act of love. You’re loving your objects, you’re creating an entire universe, so how the light comes in a room right now, how your hair is cut… it’s the details, the devil is in the details.

You use repetition of words and phrases, but also their deeper concepts, through out your book. Why is this a part of your storytelling?

I like choruses, repetitions. When I was a super in New York, five women walked past me, all talking about this pizza parlor. By the time they’d past me, they’d said “pizza” maybe ten, fifteen times. Creative writing classes say, you can’t do that. If you really listen to people, they repeat themselves; they say the same word in the same paragraph ten times. It’s my attempt to make it sound spoken instead of written. The choruses and the lists all have a sense of poetry, and music to them.

How does music influence your writing, and this book in particular?

I’ve always been so influenced by music, probably because in the early days, my mother played the piano and that was the one place we all could find solace. Some of the most wonderful times were her playing the piano with relatives over, with coffee and chocolate cake and red Jello. My mother learned to play by ear. I didn’t inherit that talent, but often when I’m sitting and typing, I’ll think, it’s very similar, so, I’m making music.

How do you write about “the other” – whatever characters feel outside your realm of experience, for example, characters and personalities not intrinsic to you? Also, how do you approach representing other races, women, classes, ethnicities? What quality in you helps you do that?

Beneath our skin, our sexuality, our gender and how it does or doesn’t fit, and our journey to make it fit, we’re all bewildered human beings. We’re all confused, none of us has any answers; anybody who says they have an answer is lying. A great Zen saying is “When you meet another person look them closely in the eye, because within those eyes there’s a great battle going on.” If we’re all just sitting down here bewildered with this huge battle going on, all you have to do is scrape the surface a little bit.

…

The African American battle may be different from that of the white Catholic kid from Idaho, but really we all have to face sex, without any clues, and face death, nobody knows about that, so I try to concentrate on our similarities. It’s really risky to write from these different cultural and racial characters in my books, but what if I just wrote about white people from Idaho?

——

Cathy Camper has written for Women’s Review of Books, Giant Robot, Cicada, Boy Trouble, Kirkus, and Wired. From 2000-2005, she served as a board member of Mizna, an Arab-American literary journal in Minneapolis, MN.