‘There Was a Sense of Family: The Friends of Mark Morrisroe’ by Teresa Philo Gruber

Author: Philip Clark

September 10, 2013

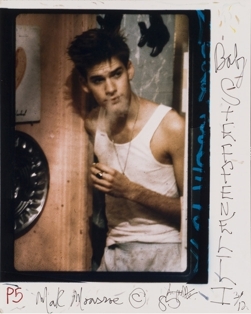

“You know, I’m going to be really famous, so you’re lucky to be meeting me.” – Mark Morrisroe, as quoted by Jack Pierson

Like its subject, “There was a sense of family…”: The Friends of Mark Morrisroe is conniving. It seems really modest—for a book about a photographer, there’s not even a photograph on the cover—but it wants to seduce you, to screw with you. It’ll assault your sensibilities, but you’ll love it anyway. It’s funny and appalling. It asks to photograph you but waits until you’re in the room to say that you’ll be naked while it happens. Its work is beautiful, but cloudy, rough around the edges (exposed binding, glued-and-stitched, looking all DIY). It’s going to be famous, and you’re going to help it get there.

Like the man himself wrote in his diary, “I, Mark Morrisroe pledge to coldly use and manipulate everyone who can help my career. No matter how much I hate them I will pretend that I love them. I will fuck anyone who can help me no matter how aesthetically unpleasing they are to me.” July 13, 1985; you can look it up. Of course, with that kind of ambition, there’s going to be a certain amount of myth-making. With Morrisroe, who died from AIDS at age 30 in 1989 and can no longer clear up misconceptions (not that he’d want to), what was myth and what was reality?

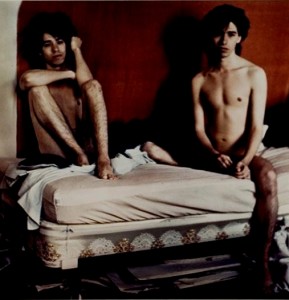

That’s one of the questions Teresa Philo Gruber of the Fotomuseum Winterthur, which holds Morrisroe’s estate, tries to answer by tracking down and interviewing Morrisroe’s surviving friends and artistic colleagues. (That’s redundant, because all his friends were artists, even if not all matched his genius.) Not everyone who could or should be interviewed was available: notably absent are Pat Hearn, a NYC gallery owner and Morrisroe’s initial executor, dead from cancer; and Nan Goldin, the best known of the so-called “Boston School” of photographers of which Morrisroe was part and whose name arises throughout the book without seeming to have been a close friend. But those who sit down with Gruber—represented in each interview, then-and-now style, by a Morrisroe photograph and by several Gruber pictures—all acknowledge Morrisroe’s roles as l’enfant terrible photographer, obsessive fame-seeker, and general shit-disturber.

Sometimes literally. Laurie Olinder remembers the time their art class had the assignment to bring or do something that no one would ever forget and Morrisroe carried in a bag of dog shit, smearing it over his chest and sending classmates running for cover. There’s the funniest story ever recorded about swastikas, as told by his longtime best friend and partner-in-crime, Lynelle White. Lourdes Sanchez recalls Morrisroe offering to cook dinner for her, but instead, high on heroin, devouring raw hamburger meat in order to disgust her. There are tales of his slashing himself in the hospital and writing messages with the blood or, in the midst of AIDS dementia, collecting his pus and broken-off scabs next to his bed. Gruber’s natural question to many interviewees—whether they visited Morrisroe as he grew sicker and sicker in a Jersey City apartment—grows increasingly uncomfortable as it becomes clear that many friends ran, alienated and unable to cope with his behavior, which was often rude or cruel, even at the best of times.

This is leavened by memories of Morrisroe’s genuine kindness and thoughtfulness. Sanchez recalls, “And if someone had bought him a really great French fashion magazine, he would give it to me as a gift. He would pick things for you. To me the thing about Mark was: if he cut the crap, he had a real social intelligence; he could really get you.” Giving away magazines, photographs, or a dress to cheer up a fellow artist who failed to win a fellowship, Morrisroe was capable of impromptu acts of generosity, an unscripted sweetness that friend after friend obviously misses. A refrain: despite any bad behavior, he was charismatic and compelling—people wanted to know and spend time with him. A second one: as John Stefanelli says, “Mark could be a really caustic person, very sharp-tongued…but it was almost always tongue-in-cheek. He didn’t really mean to be mean.”

But he meant to be famous. To that end, Morrisroe constructed a biography of himself that everyone agrees seemed like a kind of performance art, designed to shock and intrigue. There was a sense of family… sorts through much of this biography, but owing to its interviews’ Rashomon-like kaleidoscope of memories, it can’t always reach conclusions. Yes, he definitely hustled for rent money. Yes, he was definitely shot in the chest by a john, causing a permanent limp, although the details of the incident changed in its tellings. No, there’s no way to know whether he was the illegitimate son of the Boston Strangler. Lynelle White saw him being half-kept by one client who he said was a Mafia hit-man, but when everyone agrees that Morrisroe lied frequently, is this the truth? Questions of literal truth, emotional truth, photographic truth, and how truth so often cannot be determined litter the interviews. Morrisroe asked Ramsey McPhillips, his last boyfriend, to be his biographer, but McPhillips has never been able to finish the book, and he flat-out states that his draft is an intentional mix of truth and fabrication. Maybe that’s the best, or only, way to create one.

What’s certain is that the life is so compelling that it has often overshadowed Morrisroe’s undeniable photographic talent.

Gruber and Rafael Sanchez worry about this in his interview; as he says, “the truth, in itself, is quite remarkable. So once you get through all this spicy biography, the work is still there haunting you with blossoms of truth.” Morrisroe’s photographs in There was a sense of family… are reproduced only in mugshot size, so no one should approach this book without first looking at his photographs online, or better yet, in Mark Morrisroe (Twin Palms Publishers, 1999; out-of-print) or Mark Morrisroe (Ringier, 2011). His polaroids, C-prints, “sandwich” prints, and photograms—of friends in Boston, where he started out, and New York City, where he moved in 1985; of collaged physique magazines and other scraps of image and print; of himself, from his sexy early days to the x-rays and hospital photographs that exhibited his own failing body as AIDS consumed him—haunt in their murky, only deceptively-offhand complexity.

It’s impossible to see a Morrisroe photograph clearly. Try it. Something is always in shadow, painted-over, scratched, composed so that it is just off-screen, taunting you. In even the simplest portrait, there’s something that insists on being seen but that resists easy understanding. The photographs, this book of interviews, though, they’re what remain to try to make sense of Mark Morrisroe. A legacy, one photograph, one memory at a time.

There Was a Sense of Family: The Friends of Mark Morrisroe

By Teresa Philo Gruber

Moderne Kunst Nürnberg

Paperback, 9783869843797, 144 pp.

March 2013

Photos: Mark Morrisroe, There Was a Sense of Family: The Friends of Mark Morrisroe