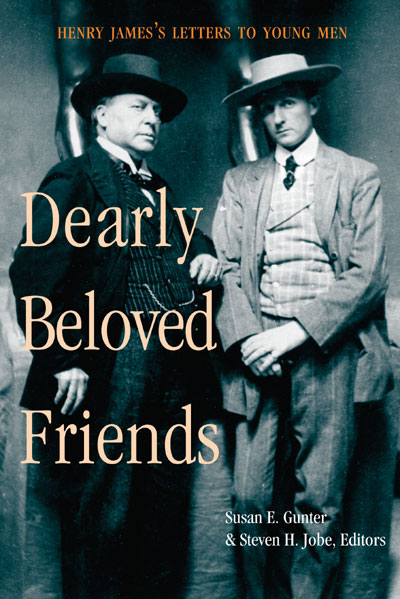

‘Dearly Beloved Friends: Henry James’s Letters to Younger Men’ Edited by Susan E. Gunter and Steven H. Jobe

Author: Randall Ivey

May 14, 2010

THE KIND AND GENTLER MASTER. For many years the seeming austerity of his private life stood in stark contrast to the baroque richness of Henry James’s prose. James never married. He never courted. He conducted no love affairs that have attained literary renown or notoriety. He was a confirmed bachelor, apparently happy with the fact and compensating for lack of conjugal communion with his many friends, acquaintances, and admirers.

Interest in James’s love life, or lack thereof, intensified in the 1960’s or thereabouts, when the private lives of many authors, both living and dead, became open to psychological speculation as keys to the meaning of poems, novels, stories, etc. Once again the question arose: what accounted for Henry James’ sterile erotic life? Did his natural puritan inclinations prohibit him from such? Had he received an injury from a pump handle during a house fire that rendered him erotically-incapable? Or was James’s true sexual preference considered so dreadfully shameful in his own time, so unspeakable even, in polite nineteenth century society that he had no choice but to keep it guarded, hidden away like one of the secrets that often preoccupy his aloof characters?

In other words, was Henry James homosexual?

The standard life of James, Leon Edel’s five-volume biography, was published in a time, primarily the 1950’s and 1960’s, when rational treatment of homosexuality was still considered non-circumspect, so Edel is nearly mum on the subject. In his revised, abridged version of the same work, published in the 1980’s, he finally acknowledges the possibility of James’s homosexuality but does so with obvious reticence. Still Edel was sufficiently fascinated by James’s sex life to commend an article by gay writer and critic Richard Hall in The New Republic which dealt with James’s sexuality and that drew the conclusion that James harbored an intense fixation on his older brother William which bordered on the erotic.

The 1970’s and 1980’s, of course, brought about much more open consideration and inquiry into the private lives of significant figures. The first reference I recall to James’s erotic life was in A.L. Rowse’s idiosyncratic, bibliography-free, but very entertaining Homosexuals in History: A Study of Ambivalence in Society, Literature, and The Arts (1977), whose title pretty much says it all. Among the “paramours” Rowse discusses in connection with James are Hendrik Anderson, the sculptor, and society maven Jocelyn Persse (a man, by the way), both of whom figure significantly in the book presently under review. More carefully researched and considered studies have followed in the more than two decades since Rowse’s book. Among them are John Bradley’s Henry James and Homo-Erotic Desire (1998) and Eric Haralson’s Henry James and Queer Modernity (2003).

The above books, and others, study the way homosexuality fits into both James’s life and his work. The present book, Dearly Beloved Friends: Henry James’s Letters to Younger Men, takes a different, more personal approach to the subject. It is, obviously, a compendium of letters to four younger men with whom James had undeniably great emotional, if not physical, attachments: the aforementioned Anderson (1872-1940) and Persse (1873-1943), as well as the American-born British writer Howard Overing Sturgis (1855-1920) and the British novelist Hugh Walpole (1884-1941). Sturgis was forty-seven at the time James met him, which makes him a “younger” man, if not quite a young man; Walpole was nineteen when he sent the elder James a fan letter. One of the (perhaps unavoidable) drawbacks of the book comes in the short section of illustrations, in which the recipients of James’s letters are all pictured well into middle or old age. James himself was fifty-six at the time he began the first of these relationships with Anderson.

The editors have hit upon an interesting concept with Dearly Beloved Friends, but I am not sure what exactly we learn from these letters about James, if anything. There are no salacious revelations a la Roger Casement; so those who might come to these pages looking for scatological details of James’s sex life would do best just to stay home. James was, in his fiction and non-fiction alike, a guarded man, a true Victorian when it came to matters of sex, and these letters show no deviation in that pattern. With Anderson, we do see what a physical man James could be and how much he seemed to crave physical contact, a thing from which he was apparently deprived all his preceding years. The letters to Anderson are filled to brimming with his desire to take Anderson into his arms, to lay his hands on the Norwegian giant, etc. “I hold you close and am ever your affectionate old friend” is a common closing line (and one of the more restrained) to these Anderson missives. Here, more than anywhere else in the book, we get a sense of how passionate James could be. We also get a sense of James’s great disappointment in Anderson’s artistic sensibility. Anderson was a sculptor of some repute whose grand dream was to construct an entire city, a World Centre of Communication, that would somehow unite the peoples of the world. The idea left the more practical James cold. He implored Anderson to engage in more modest and commercially viable works, such as the bust he made of the Master himself; such smaller pieces, James argued, would give Anderson the credibility and, more importantly, the money to pursue his larger creations. Anderson did not heed his admonitions. Today, one can safely argue, Hendrik Anderson is better known as an intimate of Henry James’s than he is a sculptor.

Art figures to some degree in the other letters, especially those to Horace Walpole, who was coming to maturation as a novelist when his friendship with James commenced; and again James pulled no punches, despite his personal affection for Walpole, in criticizing what he felt were flaws in his work. The same goes for Sturgis, the author of Belchamber and other works. In both writers James found a need for greater focus of point of view and expansion of detail and material. Still there is not enough insight into James’s views on art or his own work habits (although I suppose both are readily enough available elsewhere to where this cannot be counted as a flaw). What we do learn from the letters is how peripatetic James and his younger friends were and also how lonely James was when he was not traveling and how much he craved the company of these men. He envied Walpole’s inexhaustible vitality and energy and encouraged his activity as fodder for novels. He encouraged the social rotations of Walpole, Sturgis, and, especially, Persse. More than anything else, however, he extended frequent invitations for all these younger men to visit him at Lamb House, his residence in Rye; there is almost a plaintive note to his invitations, if not desperation.

It is unclear just how far James’s relationships with these men went, whether or not they truly crossed the bounds into the homosexual. His physical attraction to Anderson has already been noted. His letters to Persse make casual references to “intimacies” and “intercourse”, and at one point he tells Sturgis that “I could live with you.” Still one must keep in mind the conventions of the time, when florid declarations of affection between men were accepted as common totems of friendship. Walpole apparently made an advance upon The Master but was rebuked: “I can’t, I can’t,” he moaned as he turned from his pursuer. The letters themselves, of course, make no mention of this aborted seduction.

So, one leaves the letters with one’s earlier ideas about James and sex intact: his physical relations were probably limited, if extant at all. While he may have been homo-erotically oriented, his greatest love no doubt remained his work. Relations with others, no matter how genuinely rooted, provided material for the engine of creativity. And the greatest pleasure one takes from reading his letters to “younger men” is, as always, his unfailing mastery of English, his complete control of language.

It is enough to recommend the book.

——

DEARLY BELOVED FRIENDS

Henry James’s Letters to Younger Men

Edited by Susan E. Gunter and Steven H. Jobe

The University of Michigan Press

ISBN: 9780472030002

Paperback, 282p