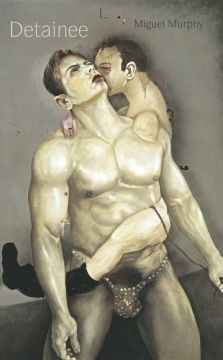

‘Detainee’ by Miguel Murphy

Author: Walter Holland

November 16, 2016

Miguel Murphy’s Detainee, a follow-up to his debut collection of poems A Book Called Rats, defies recent trends in contemporary American poetry. Murphy instead reaches back to the Spanish tradition of Federico Garcia Lorca and the drama of Jean Genet, two gay poets who wrote their work with a theatrical eye for the emotional and the erotic. He also embraces French surrealism and the work of Breton, Eluard, and Artaud, which relied heavily upon mixed metaphor and the free association of the subconscious mind.

With his streams of rich imagery, Murphy reflects the “cante jondo” or “deep song” style (found in flamenco music of Spain) that Lorca so admired and tried to integrate into his poetry. This was a style of earthiness and passion, of the body and struggle.

Murphy’s are dark poems, drawing on dramatic juxtapositions of beauty to ugliness, the sublime to the demonic, and the grotesque to the familiar; assaulting the senses as they bring a brutality of language to the page. Murphy’s is the world of the gay painter Caravaggio, of Baroque art, which was characterized by great drama, rich, deep color, and intense light and dark shadows. As in “chiaroscuro,” a painting technique of the Baroque era, light and dark are boldly contrasted to create dramatic imagery. Murphy plays with a palette of sharply clashing images.

Like Genet, he plunges us into a world of sex and the violence. The male body and its desire are behind this explosive fury of language. In this, he is a descendant of Lorca, Genet, and Arenas, whose deeply sensual works took us to the shadow lands of homoerotic desire. It is a daring move. One that risks a laceration of the poems with operatic verismo. These are poems not for the faint of heart and may strike the modern ear as indulgent and overwrought, accustomed as we are to less stridency in our poetry.

The animalistic contrasted to the human is one constant in these poems as each poem is a maelstrom of primitive emotions. From the beginning of the collection, “Thorn” is addressed to a dog, an animal, which has harmed itself (?) and is now held in a hospital for animals. The “I” and “you” of the poem seems somewhat fluid alternating between beast and master, but the language is raw and sharp:

My eye never filled with blood.

I never asked why

I was drugged and held down. Mesmerized.

I wasn’t a two-headed dog: two faces

biting a squeal

in the University Hospital for Animals.

I never transformed daylight

dismembering doctors along dark nails.

I never growled

like you–never crouched in fear.

Tail, teeth, mouth eye, spine.

I never had power

when I was awake to flee.

In “Enjoy Flesh!” the second poem of the collection, we have:

If we want to embrace

absence, a cocktail

party will do. Fat olives. The dark sparkling

cherries dipped in rum. Drinks

splashing their brains

against the cold, blue-violet velvet

sky. Our loves, our loves never

come back & that is why in our sicknesses we don’t

know how to live with the dying

windows. Here is the last

tangerine light, its rind.

And later:

hold him in our arms & shave his head in our hands,

lying the fragile

collapsed husk of his body down

in the cool white sheets like our beloved

signing our curses upon his chest.

This is a theatrical language from another time but bridges seamlessly with the present. “We enjoy/our eyes dissolving like aspirin…” A pastiche of different vernaculars:

after lovemaking

the darknesses in the bodies we have known

O pale flickering

embrace. O Synapse of our deathsleep, unscathed.

Like countless gay artists before him, Murphy perfects an affectation that branded gay men as effete, drama queens. Men that knew their art history like the back of their hand and found in the melodramatic and the mannered a masque for their own gay voices.

But there is a sense of the confessional at work here, too. Murphy reveals glimpses of his childhood and family history. In “Summer of the Hatchet,” he tells us about “the mines in Colorado/ where they pulled my father & my father’s father/ from the pits, their lungs/ soaked with coal like wings of wet black gothic/ velvet.”

And in “Whose Hands He Worked” Murphy tells us:

________My grandfather

touched my cock.

I’m not about to tell

it was o.k., but it

was one way I learnedan urge can make the reasonable

person inside

disappear–it was the way

I learned.

Contemporary language and events wend their way in and out of his work. In “Like Beauty” Murphy writes:

Admit it in the videogame

of the government’s boyish wars

the arcade blue crosshatch

of Tomahawks into Baghdad

unburies the moon’s neon thorns

its empty theatre of skulls

& the red black tatters of war. Nightmare

like Beauty admit it–The TV

muted because we wanted torture admit it…

This repetition of the phrase “admit it” throughout the remainder of the poem acts as a dramatic refrain and resonates with our own American denial of the horrors of the Iraq War.

who hasn’t yet softly

crushed his wife’s pink nipple

the face of his newborn

daughter or the bullet

sighing into his life like

horror & liberation admit it admit it…

The excessiveness, the intoxication, the Baroque ferocity in this work will not be to everyone’s taste. But no one can deny Murphy’s unique voice and supple lines, surprising as they are tortured, self-involved as they are expansive. These are dark interiors Murphy describes, caves of the heart, “That red/inner lining of the self, that stream/ shot through the skull, red jet/through a bullet’s/ hole.”

Detainee

By Miguel Murphy

Barrow Street Press

Paperback, 9780907318401, 72 pp.

April 2016