‘Mark Dirt’ edited by Nicole Katz, Mathew Swenson, and James Brundage with Ramsey McPhillips

Author: Philip Clark

November 11, 2013

These days, even bands without much in the way of A-sides have seen fit to release an album of B-sides. For any musician with enough fame or longevity, the record company clears the vaults, intriguing fans with unreleased songs, alternate takes, live performances, and demo recordings. At their best, these albums can provide a stronger sense of a musician’s artistic development and occasionally reveal a should’ve-been-a-hit song buried amid the outtakes.

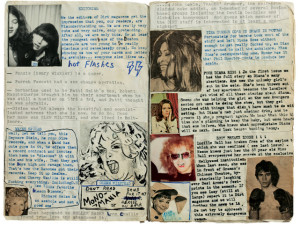

Following such recent books as Mark Morrisroe (2010), an extensive catalog raisonne, and There was a sense of family…: The Friends of Mark Morrisroe (2013), Mark Dirt is Mark Morrisroe’s B-sides album. Morrisroe didn’t have the longevity, dying from AIDS at age 30, but he had the fame and notoriety to justify the release of his ephemera: letters, song lyrics, hospital records, art school reviews, exhibition advertisements, and excerpts from his collaborative Boston punk-scene ‘zine, Dirt. These are mixed with stray photographs, sometimes of people mentioned in the ephemera, including Pat Hearn, Stephen Tashjian (Tabboo!), Philip Taaffe, Gail Thacker, and Morrisroe himself.

So does the collection of these objects add up to anything? Loving Morrisroe’s photography as much as I do, and being as intrigued by his fast, intense, talented life as I am, I regret having to say: no, not particularly. Ramsey McPhillips, Morrisroe’s surviving partner, writes, “Interviews, hospital records, police records, school files and periodical research are merely an addendum to oral histories that are partially fabricated, partially the truth….Those unwilling to suspend their disbelief are missing a great show.” But herein lies the problem with Mark Dirt. Anyone who is willing to suspend disbelief and go along for the Morrisroe ride has probably already seen the photographs in previous publications and has the option of reading There was a sense of family…for those revelatory oral histories. What’s here is, at most, the addendum that McPhillips indicates.

Despite this, dedicated Morrisroe fans will probably still want the book. There is intrigue, for example, in seeing the actual documents from Morrisroe’s time at Boston’s School of the Museum of Fine Arts, some of which have been much-quoted in the literature surrounding his life and career. The editors begin with the school’s acceptance of Morrisroe’s application in 1977 and a 1982 letter where the board of trustees awards him a $10,000 traveling scholarship. The next dozen pages, though, detail how the intervening years had their share of drama, with several professors at the school viewing Morrisroe as less-than-talented and unteachable.

Their criticisms early in 1978 called Morrisroe and his work “superficial,’ “juvenile and ill-considered,” “sloppy,” and “shallow”; one, Donn Moulton, wrote, “In my opinion, this student should never have been admitted. The faculty of this school are not prepared to deal with a ‘disturbed’ student of this sort.” A passionate, five-page, hand-scrawled letter from Morrisroe responds to these professors’ attempt to have him

denied credit and possibly expelled, arguing, “I need a place to work where I can do what I want, and have it criticized—not me. I want to be told how I can make it better—not me” and “I can’t pretend I’m not upset or offended by this show of narrowmindedness. Moulton could be a Nazi from what his attitude shows.” The letter goes on the offensive at times, but it also shows Morrisroe as a wounded boy, capable of hurt, a side not always seen in writing about him. Better-known is the Morrisroe who, in reviewing a fellow student’s art, wrote, “My advice to Joanne is that perhaps she should consider doing pastel portraits at tourist attractions or maybe Woolworths. You can’t make good art unless you have something to say.” At the least, items like the letter to his professors, or the painstakingly hand-copied lyrics to popular songs of romantic despair, show his other, more vulnerable side.

It is moments like these that make Mark Dirt worthwhile for those who are already familiar with his photography and with the now-growing body of literature surrounding him. Understand going in that the book is a grab-bag of only occasionally revelatory materials and it is much easier to appreciate the show that McPhillips promises.

Mark Dirt

Edited by Nicole Katz, Mathew Swenson, and James Brundage with Ramsey McPhillips

Paper Chase Press

Paperpack, 9780985204419, 170 pp.

September 2013