Gore Vidal Writing As Edgar Box

Author: Drewey Wayne Gunn

February 28, 2011

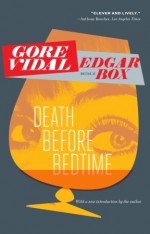

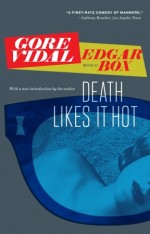

Fans of Gore Vidal will not want to miss the Vintage Crime, Black Lizard reissue of his three Edgar Box mysteries, originally published in the early 1950s. Even under a pseudonym, they are vintage Vidal. Readers looking for a gay mystery, however, should search elsewhere.

Peter Cutler Sargeant II, their hero and first-person narrator, is the consummate womanizer. Always on the prowl for attractive women, invariably he is successful in quickly having his way with each one he sets out to bed—though in Vidal’s portrayal of current mores, it is a toss-up on who actually seduces whom.

A number of gay characters do appear in the first novel, Death in the Fifth Position (1952), set in the world of New York City ballet. But Sargeant’s several encounters with them lead to such exchanges as this, with a French dancer:

“Such good boy,” said Louis, holding my arm for a minute in a vise-like grip. “Some muscle!”

“I got it from beating up faggots in Central Park,” I said slowly; he doesn’t understand if you talk fast.

The hero allows himself to spend an evening on the town in Louis’s company. Summing up their visit to a gay bar in the Village, Sargeant says:

I thought I knew a great deal about our feathered friends, the shy, sensitive dancers and so on that I’ve met these last few years in New York, but that night with Louis was an eye-opener … it was like those last chapters in Proust when everybody around starts turning into boy-lovers until there isn’t a womanizer left on deck.

Gays do not show up at all in the second novel and for only a brief glimpse in the third, where they are again identified by the code word “sensitive,” along with the observation that they are “tender with sibilants.” Such comments pander to straight attitudes of the time, but their gratuity somehow seems all the more unpleasant coming from a character in a Vidal novel. It is easy to forget that he drew far more vicious portraits of homosexuals in The City and the Pillar (1948) and The Judgment of Paris (1952).

The mysteries as mysteries hold up quite well. All entertaining cozies with a small cast of suspects and clues fairly presented to the reader, they are worthy descendants of the golden age of detective fiction. Vidal credits Agatha Christie as his model. Our amateur sleuth is Harvard educated and has served three years in World War II. After a stint as an undervalued journalist on a New York newspaper, he has created his own one-man public relations firm. That occupation gets him invited into the various social worlds in which the mysteries are set.

Having identified the killer who cut a cable and sent a ballerina plunging to her death, Sargeant is next summoned to Washington, D.C., to help with a Senator’s presidential run in Death Before Bedtime (1953). He arrives only shortly before the Senator meets his death in a mysterious explosion in his own home.

The third mystery—the best executed of the lot—finds him taking on a more mundane task of handling the publicity for a party to take place in the near fashionable world of the Hamptons. This time he must wind his way through an ingenious plot in order to discover what really happened when his hostess’s niece drowns in plain sight of her husband and the rest of the guests, four sleeping tablets in her digestive system.

This novel, Death Likes It Hot (1954), lays the premise for a fourth novel to be set in a circus milieu—unless this is just Vidal having fun with the genre’s conventions. In the set of new introductions that he has written for the reissue of the three novels, he repeatedly stresses his editor’s advice, “Write what you know,” and I can find no evidence that he was intimate with circus performers.

Vidal’s skill at creating memorable characters did not desert him even as he wrote at high speed. Members of the ballet company and various houseguests at the Hamptons in particular remain vivid in my mind: the choreographer, the gay dancer, a Russian director, a somewhat sexually unsettling brother, a ditsy writer for children, a Harvard student down for the weekend. Each of the police detectives assigned to the case has a distinctively different personality, and none seems a cliché. Other than the sleuth, only three recurring characters appear, all in minor roles.

The three books were written during the same period he published The Judgment of Paris, his bildungsroman set among expatriates in Italy and Egypt, and Messiah (1954), his satire about a media-fueled religious cult. There also appeared in the same period an adventure story set in Egypt, Thieves Fall Out (1953), published under the pseudonym “Cameron Kay.” (Earlier, in 1950, he published his first pseudonymous novel, the Hollywood melodrama, A Star’s Progress, “by Katherine Everard.” No gay critic fails to see this as a sly allusion to the Everard Baths.) These would be his last completed novels for ten years, while he turned instead to the more profitable world of writing scripts for television, Hollywood, and Broadway.

The time frame of the novels is during the heyday of McCarthyism. One of the more unlikeable characters in Death in the Fifth Position brags, “Mister, we have spent close to a hundred thousand in the last year to root Reds and other perverts out of our way of life, in government, entertainment and the life of everyday … and we’re doing it.”

Unless he revised the text after the fact (I have not seen the first printing), Vidal’s portrait of the choreographer Jeb Wilbur provides an absolutely uncanny prophecy of Jerome Robbins’s damaging testimony before the House Committee on Un-American Activities the spring following the book’s publication. Little is made, however, of the Wisconsin Senator’s hypocritical hatred of homosexuals. Vidal seems more fascinated by Huey Long (and, for some reason, Margaret Truman) than by Joseph McCarthy.

The Box novels were apparently well reviewed. I don’t know whether anyone tried to guess who this new author was. But Vidal’s distinctive voice, which found its clearest and greatest expression in his essays, can already be heard. Speaking through the mask of his amateur detective, he describes the Senator thus:

He was […] a near-idiot with a perfect Senate record of obstruction. He regarded the administration of Chester A. Arthur as the high point of American history and he felt it his duty to check as much as possible the subsequent national decline from that high level.

Vidal gets in a marvelous ironic barb when he has an unsavory character state, “In a true democracy there is no place for a difference of opinion on great issues.” And one can hear the emergence of the patrician stylist in one of Peter Sargeant’s asides:

“Did they tell you who he was going to arrest?” (I would rather say “whom” but

my countrymen dislike such fine points of grammar.)

Vidal’s introductions to the series credit Victor Weybright, one of the creators of the New American Library paperback series, for suggesting “Edgar,” in honor of the once famous British mystery writer Edgar Wallace. Vidal goes on to say that “Box” came about as a result of their attending a publisher’s party in honor of a couple (obviously script writers Muriel and Sydney Box). In his 1995 memoirs, Palimpsest, however, Vidal asserts that “Edgar” honors Poe, saying, “If I was going to whore, I might just as well follow in a master’s footsteps.” He never mentions one of Poe’s more obscure mystery stories, “The Oblong Box.”

After each being reprinted several times in their NAL-Signet incarnations (“Spillane in mink” shows up as a blurb on some printings), the three novels were united between hard covers by Random House in 1978 as Three by Box: The Complete Mysteries of Edgar Box. Vidal’s name is found nowhere within the book itself, not even on the copyright page, but the dust jacket revealed the identity of the author—which was already pretty much an open secret.

From the advance copy that the publisher sent out to reviewers, it would appear that the new three-volume edition, “by Gore Vidal writing as Edgar Box,” will use the same plates as this omnibus volume. I hope some editor will look them over carefully before they are printed. The once fine art of proofreading was obviously already becoming lost by the end of the 1970s.

——

Death in the Fifth Position

9780307741424

Death Before Bedtime

9780307741431

Death Likes It Hot

9780307741448

Vintage Crime / Black Lizard

$14.95 each