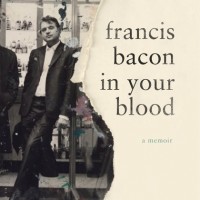

‘Francis Bacon in Your Blood: A Memoir’ by Michael Peppiatt

Author: Jennie Rathbun

January 17, 2016

In 1791 Boswell published his Life of Samuel Johnson, launching a literary genre that remains our most entertaining species of memoir, the tale of friendship between two people, written by the pair’s less famous member. The keen pleasure afforded readers of such books derives in large part from the high concentration and quality of the gossip they contain. There is no shame in our curiosity about the table talk, bad marriages and moral lapses of cultural icons. Anecdotes and even quotes from these books lodge like cockle burrs in the memory. While reading Michael Peppiatt’s wonderfully indiscreet memoir of his thirty-year friendship with the celebrated British painter Francis Bacon, I was reminded of Sir Vidia’s Shadow, Paul Theroux’s 1998 account of his scary friendship with V.S. Naipaul.

This chatty memoir embodies a double portrait of the younger narrator and his older subject. As readers we identify most easily with the narrator. Here it’s more than an incidental pleasure to watch Peppiatt, under Bacon’s loose protection, growing up and establishing himself as an art critic. The friendship began in 1963 when the author was 21. Michael Peppiatt was at Cambridge, editing the student magazine when he decided to devote an issue to British art, a subject he knew nothing about. He had the great good fortune to obtain an introduction to Bacon, then 53, and conducted his first interview with him over oysters and Chablis in a Soho restaurant called French House. (They were introduced by the gay Vogue photographer John Deakin who would later call Peppiatt “Bacon’s Boswell.”) Peppiatt and Bacon became friends immediately and stayed on remarkably good terms for the next three decades, as the younger man accompanied Bacon on nightly hard-drinking tours of Soho’s demimonde.“My gilded, gutter life” was the painter’s summarizing phrase for it, and Peppiatt is an ideal narrator, candid about his own inner conflicts, setbacks and rare terrifying moments when Bacon turned on him in anger. He knows what Bacon was like, probably better than anyone else living, having written the definitive biography of the painter, Francis Bacon:Anatomy of an Enigma, as well as several other books on him. He sets out his intention in the Preface:

This is the subjective story of two lives, focusing on the complex, volatile relationship that bound Bacon and me together over those three decades. Drawn from diaries and records I kept at the time, it presents an intimate, revealing portrait of the artist as friend and mentor. Bacon comes across here in ways that no formal biography could convey: close up and unguarded, grand and petty, tender and treacherous by turn, and often quite unlike the legend that has grown up around him.

One of the memoir’s greatest strengths is the sense it conveys of Bacon as a social animal, gregarious and full of contradictions. He loved gambling, good food and good wine, and could be generous and funny with the people he liked, while coldly dismissive of his fellow artists, a trait he shared with Naipaul, who was given to murmuring about other writers that he didn’t “think there was much there.” Bacon had little use for the work of Jackson Pollock, Willem De Kooning, or Robert Rauschenberg, and he preferred Andy Warhol’s films to his art. There’s a funny scene when David Hockney enters a Paris restaurant and “comes over to kiss Francis affectionately on either cheek. As David moves on, Francis takes out a handkerchief and wipes his cheeks very elaborately.

‘Now I wonder why he did that?’ Francis says to me. ‘I suppose he must have some ghastly disease.’”

When Peppiatt first met Bacon, the artist had reached a peak of popular acclaim, coming off a retrospective the previous year at the Tate Gallery in London. He would have a second Tate retrospective in 1985, an unheard-of honor for a living artist. He died in Madrid in 1992, leaving an estate valued at eleven million pounds to John Edwards, his lover during the last twenty years of his life. In 2013 his triptych, Three Studies of Lucian Freud sold for over a hundred and forty million pounds, setting a world’s record for art auction prices. For any reader whose only knowledge of Bacon comes from his paintings of screaming popes, this convivial memoir will humanize the artist behind the work. His friends included celebrities, bar owners, criminals and royalty. Peppiatt knew all of Bacon’s inner circle, most of whom seem to have accepted his presence, with the glaring exception of George Orwell’s widow, Sonia whose persistent dislike is shudderingly funny. We get to know Lucian Freud, Michel Leiris, and Muriel Belcher, the formidable lesbian proprietress of The Colony Room in Soho, a private drinking club.

Apart from Peppiatt who is straight, the most important men in Bacon’s life were his three lovers, Peter Lacy, George Dyer and John Edwards. Tragedy shadowed the artist’s romantic liaisons, beginning with his relationship with Lacy, a handsome alcoholic ex-RAF fighter pilot whom he met at Muriel’s. His description of falling in love for the first time after the age of forty is as coldly funny as anything out of Beckett:

Well, what Peter himself liked was young boys. He was actually younger than me, but for some reason he didn’t seem to realize it. It was the most total disaster right from the start. Being in love in that extreme way—being utterly obsessed by someone as I was–it’s like having some dreadful disease. I wouldn’t wish it on my worst enemy. And we had these four years of continuous horror, with nothing but violent rows.

Word of Lacy’s death reached Bacon just as his 1962 Tate retrospective was opening. Next was George Dyer, a petty thief from Soho who would become Bacon’s muse and model. History would repeat itself in the most macabre fashion, when in 1972 Dyer committed suicide in Bacon’s Paris hotel room on the eve of the artist’s exhibition at the Palais Royale. After that Bacon swore off intimate relationships but he soon began seeing John Edwards, who was kind and markedly stable compared with Lacy and Dyer.

Above all, Bacon was a witty and amusing companion. By the middle of the book, most readers will find themselves envying the author’s unique access to a man often hailed as the most important painter of the twentieth century. We are fortunate to have this record of his conversations on art, life, sex, success, aging, guilt and heartbreak. Peppiatt gives us the man in full, wisely leaving in Bacon’s repetitions on various subjects. There is also the devastating one-off remark. Strolling past police cars at the scene of a murder-suicide in a Soho flat, Bacon says, “‘Well, I suppose it’s a gesture. But it’s a gesture one can make only once.’”

Francis Bacon in Your Blood: A Memoir

By Michael Peppiatt

Bloomsbury

Hardcover, 9781632863447, 401 pp.

December 2015