Wrestling with Gods and Monsters: In Conversation with Michael Thomas Ford

Author: Vince Liaguno

December 6, 2016

“The best horror stories, in my opinion, takes characters and somehow makes their secure worlds suddenly insecure, even deadly. Unfortunately, this is something many queer people can relate to from personal experience.”

Michael Thomas Ford’s impressive literary catalog speaks of a chameleon-like muse who has inspired the scribe’s journey from an award-winning essayist and humorist to an acclaimed young adult author to the award-winning author of a successful line of gay-themed adult novels for Kensington Books that captured what it meant to be an everyday gay man living at certain points in modern history.

Lambda Literary recently sat down with the affable Ford who, at 48, is exploring the weightier themes of spirituality and self-actualization that come with middle age in his latest novel, Lily.

From the publisher:

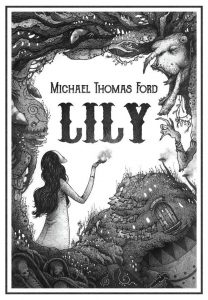

Lily is a girl who discovers she has the ability to see how others will die simply by touching them. Only she doesn’t want this gift, and takes extreme measure to protect herself from it. When her mother–because every fairy tale has to have a wicked (step) mother – sells Lily’s services to an evangelical preacher and his wildly popular travelling tent revival, Lily is torn away from the idyllic place she’s always known as home and thrust into a world of greed and manipulation that threatens to destroy her unless she can find a way back….if she survives the quest the old witch Baba Yaga has given her…or the attention of the tent revivalist who promises to save her soul.

Where did you draw the inspiration for Lily?

I started writing the book more than 20 years ago. I was unhappy with what I’d been working on at the time, and I decided to take the old advice of writing the book I’d always wanted to read. I wrote about things I’ve always loved: magic, traveling carnivals, Baba Yaga, curses, changelings, devils, clowns. I threw in everything I found interesting, and let the story go where it wanted to go. But I didn’t know what it was all really about, so I eventually stopped and put it away for a long time. I pulled it out a couple of years ago, read what I’d written, and thought, “Oh, so that’s what it’s about.” I realized I was writing about queerness, and having something inside of you that you’re afraid of and that other people tell you that you should be afraid of. Once I realized that, I was able to finish it. Sometimes I don’t always know what the real story of a book is for a little while. In this case, it took longer than usual.

Spirituality is a recurrent theme in both your fiction and non-fiction work. How does spirituality factor in to Lily’s journey in the new book?

One of the things I wanted to write about was how the promises of evangelical Christianity might be viewed by someone whose worldview is completely different. My childhood was defined by Christianity. My mother became a born-again Christian when we were very young, and that became her, and therefore our, entire world. It’s all I knew, and because we lived in a fairly isolated place without much diversity, I didn’t really know that not everyone lived like this. It wasn’t until I was an adult and would tell people stories about how I grew up, and they’d look at me like this was absolutely insane, that I thought, “Oh. Maybe this wasn’t all that normal after all.” I wanted to write about what this world I grew up in might look and feel like to someone dropped into it with absolutely no frame of reference, which is what happens to Lily. She comes from a place where no one has heard about big-G God or encountered Christianity, and suddenly she’s told (as I was) that this God has all the answers, and that she needs to believe this and that and do this and that to be happy. And just as I did, she finds out that this isn’t true, and learns that she has to forge her own path. I also put the fairy-tale witch Baba Yaga in there as someone who views Christianity from a perspective of having encountered lots of different gods and beings that think they’re gods, and can comment on what’s going on in a way that a child such as Lily can’t due to her lack of experience. My own spirituality now is more or less pagan in nature, and this story is, at least in part, about my wrestling with what I was brought up with when I found it didn’t fit my reality.

The publication of Lily brings you back full circle (pardon the literary pun) to where it all began for you in the young adult market. Do you see Lily as the culmination of your YA efforts that preceded it?

I’m probably more known for my adult books, but I’ve actually always considered myself primarily a YA writer. I wrote 25 novels for young readers before I wrote my first novel for adults. I really started writing novels for adult readers almost by accident, and ended up staying there far longer than I expected to. We didn’t position Lily as either a YA or an adult book, so it’s been interesting to see who reviews it as YA and who reviews it as an adult book. I don’t think it matters either way, as those lines have become so blurred, and I really didn’t think about a specific audience while writing it. I think younger readers will relate to Lily’s experience of discovering her sexuality and feeling like an outsider, while older readers will connect with both that theme and the other themes in a slightly different way based on their own experiences, so it works on multiple levels and for multiple audiences.

In chatting earlier about the book, you mentioned the unique differences in the way the book has been received from the various genres in which it falls – young adult, horror, LGBTQ. What’s surprised you most about those different critical and/or reader receptions?

I had no idea what to expect from this book as far as reader response. It’s such an odd book, and in many ways doesn’t fit neatly into any category whatsoever. But you have to call it something, and we decided to go with dark fantasy. Then it unexpectedly gained traction in the horror world, thanks largely to the enthusiastic support of writer Livia Llewellyn and Monica Kuebler of RUE MORGUE magazine, and now that’s where it seems to be getting the most attention. The YA world has also been very welcoming, as have queer readers, I suspect mostly because they already know my name and are willing to take a chance on something different from me. But I’m a new name to a lot of horror readers, which might make it easier for them to approach Lily with no expectations. Everyone seems to find something different in the book to connect with, which of course is enormously gratifying to me as a writer.

I had no idea what to expect from this book as far as reader response. It’s such an odd book, and in many ways doesn’t fit neatly into any category whatsoever. But you have to call it something, and we decided to go with dark fantasy. Then it unexpectedly gained traction in the horror world, thanks largely to the enthusiastic support of writer Livia Llewellyn and Monica Kuebler of RUE MORGUE magazine, and now that’s where it seems to be getting the most attention. The YA world has also been very welcoming, as have queer readers, I suspect mostly because they already know my name and are willing to take a chance on something different from me. But I’m a new name to a lot of horror readers, which might make it easier for them to approach Lily with no expectations. Everyone seems to find something different in the book to connect with, which of course is enormously gratifying to me as a writer.

Lily is a return of sorts for you, dipping your toes back into the adult horror genre. What is it about horror that appeals to you– both as a writer and a reader?

I’ve always loved dark stories. When I was little, I often sympathized more with the so-called monsters in stories than with the good guys: Jadis in the Narnia books, Mombi in the Oz stories, Hel in the Norse myths. I rooted for the wolf in “Little Red Riding Hood,” and found endings where everyone lived happily ever after irritating. I find the motivations of “evil” characters much more interesting to explore, because generally they come from a place of being deeply damaged, and damaged things of all kinds appeal to me more than shiny, perfect ones. I also love reading stories where a seemingly safe world proves to be anything but, and I like writing those stories because they’re simply more fun. I grew up reading dime store paperback horror novels and watching creature features on Saturday afternoon TV. I always wanted to be a horror writer, and my first novels for young readers were all supernatural-themed. I was even a finalist for the Horror Writers Association’s Bram Stoker Award in the Work for Young Readers category in its first year. But then publishing made one of its cyclical changes, and suddenly horror was out and nobody wanted to publish it. So I switched gears. Now, 25 years later, horror is big again, so maybe I’ll get a second chance.

What is it that lends the LGBTQ experience so readily to horror?

The experience of being an outsider and of potentially being subjected to forces that want to harm you because of your difference. The best horror stories, in my opinion, takes characters and somehow makes their secure worlds suddenly insecure, even deadly. Unfortunately, this is something many queer people can relate to from personal experience. What I think is interesting, though, is that because as queer people we’re often used to confronting and dealing with these kinds of threats, it can make queer characters more successful at combating whatever it is they’re fighting. Characters who haven’t encountered much that threatens their existence are more easily upset or overwhelmed, but a character who has faced adversity is more likely to say, “Soul-sucking zombie werewolf from outer space? Pfft. If I can take down those idiots who didn’t think I deserved the same rights that they had, I can handle this.”

I’ve debated this with other queer writers, but is queer horror still a viable sub-genre that’s necessary to carve out? Or have our gains as a community overall erased the need for such specificity?

People will always want to read stories that contain characters who reflect their own experiences. When we have some kind of personal connection to the characters in a story, it makes it easier to care about what happens to them. Queerness is one of those things that can make readers go, “Okay, this person and I have something in common. I can imagine myself in this situation too.” It’s a kind of shorthand that helps develop a reader/character relationship. As to whether or not queerness itself is something that can inherently be the subject of horror writing, that’s trickier. In the past, subjects like AIDS and gay-bashing have been themes of what was termed “queer horror,” and I think it sometimes worked as a way of commenting on social issues of a particular time. I think we’ve moved beyond that, and horror stories centered around those things seem dated. But are there other aspects to queerness still to be explored? I think so.

The question really becomes what about this character’s queerness lends itself to the horror of this situation? I’m working on a novel right now about a family who find themselves caught up in a fight for survival against both supernatural elements and their own community. I wrote the first draft with the couple being a mother and a father. Then I asked myself how the story might be different if, instead, there were two fathers. Would their motivations be different? Would their reactions to the situation be different? Would the theme of the novel change, or be better amplified, if the couple is queer? I do know that in some ways it’s easier for me to write the characters as queer men, and perhaps I even care a little more about what happens to them. But does it change the story? And would it change how readers react to it? Curiously, I think a lot of people assume horror writers and readers are much more conservative than they are. There’s been a lot of very nasty infighting over the past few years in the related fantasy and science fiction communities, where conservative voices have decried what they think is a trend of championing diverse voices in the name of political correctness. I haven’t seen any of that grumbling in the horror world, although I’m sure it exists to some degree because people are people. But in general I think today’s horror audience is much more willing to read about characters who aren’t like them. In the past, the fear was that having any queer content at all would make it difficult to sell a book to wider audiences. And I think that was a valid fear. I don’t know how true it is today. I think a lot of us who have been doing this for a long time still tend to worry about things we no longer need to worry about.

We’re both men of a certain age–specifically, middle age. We came of sexual age during the advent of the AIDS crisis and the plague affected us in a unique way, one that you touch upon–at least symbolically–in Lily. And it’s not one that’s been widely explored in fiction in terms of the gay male experience. Care to elaborate on this a bit?

Somewhere in the middle of writing Lily, I realized that I was in part writing about how I felt as someone who came of age during the height of the AIDS crisis. I grew up in a rural area, then went to a Christian college that was also a very closed environment. In 1989, a few months before I turned 21, I graduated and moved to New York, as I’d gotten a job in publishing. AIDS was, of course, the dominant factor in gay life at the time. So there I was, finally in a place with other gay people and desperate to live as an out gay person, and yet I was absolutely terrified of becoming a sexually active gay man. Not only did I have no frame of reference for how to do it (apart from having read Gordon Merrick novels, which terrified me), I was afraid that getting close to another man would be a death sentence. It was also a very strange experience for me as someone who wanted to be a writer. There I was, in arguably the most literary city in America, experiencing the single greatest event that will probably ever affect gay men, and I was strangely removed from it.

Everyone seemed to be occupied with watching their friends die, with being ill themselves, or with documenting this experience they were having. My experience, by comparison, seemed unimportant. Here there was an entire generation of gay artists (and gay men in general) being wiped out, and I was afraid to have sex for the first time because I might get sick. It seemed insignificant in comparison to having all your friends taken away or being sick yourself. I went to ACT-UP meetings, and marched, and got involved, but at the same time, I felt like an impostor in a way because I felt like my own fears and experiences were self-indulgent compared to what was happening to the people around me. It wasn’t until years later that I realized that this experience of mine really was something unique and worth documenting, and that those of us who essentially put off living our lives out of fear were also casualties of the plague. It was Felice Picano who said to me, “You have to write about this.” But I still didn’t know how. It wasn’t until I was writing the character of Lily that I realized I was writing about how I felt in those days. She feels burdened by her gift/curse, which happens to be an invisible one in the way that being queer is and which is also very much connected to her awakening sexuality. And although she longs to be loved, she’s terrified to touch anyone or be touched by them because that’s how she sees their deaths and she finds it overwhelmingly sad. She’s also afraid that she might somehow pass along what’s inside her. It’s such an obvious metaphor, and I can’t believe I didn’t see what I was doing, but sometimes the subconscious knows things long before the conscious mind does.

Who are some of your favorite horror writers and works in the genre that have informed your own?

I will give what seems to be the answer everyone who writes speculative fiction says lately and say that Shirley Jackson was the earliest and strongest influence on me. We read her short stories “Charles” and “The Lottery” in my 7th grade English class, and they changed my life. I’d never read anything like them. The Haunting of Hill House is one of the few books I can read every year and still enjoy. I also reread Frankenstein every couple of years, and continue to love Shelley’s storytelling and use of language. As far as contemporary writers, Ramsey Campbell’s The Darkest Part of the Woods is a favorite, as is Adam Neville’s The Ritual, Thomas Tryon’s Harvest Home, and all of Angela Carter. I’ll read anything by Ian Rogers, Gemma Files, and David Nickle. I also try to read a short story a day by someone I’ve never read before, which is a great way to discover new voices. I frequent sites such as The Dark, Uncanny, Nightmare Magazine, Lightspeed, Gamut Magazine, and Tor.com and pick things at random, and I’ve found a lot of good things that way.

It’s been nearly seven years since your last–for lack of a better term–commercial adult fiction, with 2010’s The Road Home (which was a finalist for the Lambda Literary Award for Gay Men’s Romance). I remember early praise for your first Kensington title, Last Summer, and more than one reviewer likening it to Armistead Maupin’s seminal Tales Of The City. Any plans to revisit any of the gents from those six novels and perhaps continue their stories?

Yeah, it’s been a while since I’ve put out a gay-themed novel. The publishing world really changed for writers of gay-themed books with the closing of most of the gay bookstores, the demise of Borders, and especially the loss of the InsightOut book club. Those were the main outlets for our books, and without them, sales dropped alarmingly, literally to almost nothing. I don’t think most people really realize the enormous impact the loss of our queer spaces has had on our artistic community. It made me a little depressed, so I took a break from publishing. I also started caring full-time for my mother, who has late-stage Alzheimer’s, which takes up a lot of time and energy. All of which is to say, I’m often asked when my next gay-themed novel for adults will come out, and I don’t have an answer for that right now. And yes, I’m often asked if I’ll write a sequel to Last Summer. I actually have one outlined, but I don’t know if I’ll ever write it. I kind of like leaving those characters in that time and place. There are certain characters who have stuck with me–Billy from my novel What We Remember, for instance, and Jeff from my YA novel Suicide Notes – and I sometimes wonder what happened to them later on and think about writing about them. But readers often have very distinct ideas about what they want to happen to characters after a book is finished, and I think whatever you write will disappoint someone. It might be best to let people have their own sequels in their minds.

What are you working on next?

I currently have a queer-themed YA novel making the rounds with editors, which I’m really excited about. It’s quirky and odd, filled with magical realism, and I absolutely love the characters in it and their story. Also, as I mentioned earlier, I have a horror novel in the works. Right now, I’m finishing what I consider the follow-up to Lily, although it has nothing to do with the characters from that book. It’s about a boy and a mermaid, and it too is about queerness and identity and how those of us who don’t fit in one place or another end up making our own lives and communities out of what we find around us. And for the past little while I’ve been working on a really fun project, a series of novellas starring some of the favorite contestants from RuPaul’s Drag Race. The first book I did, with Sharon Needles, is already out, and there are more on the way shortly. Anyone who would like to keep up with what I’m doing can add me on Facebook, follow me on Twitter at @AuthorMTFord, or visit my website at www.michaelthomasford.com.