Tanith Lee: Channeling Queer Authors

Author: Craig Gidney

September 13, 2010

The prolific author Tanith Lee—almost 300 short stories, over 90 novels—is something of a legend in genre fiction. Her vast output includes science fiction, fantasy, horror, young adult, historical and mystery. She has won major awards, including the World Fantasy Award (twice) and her fiction has been widely anthologized. She is known for her lyrical style and strange plots.

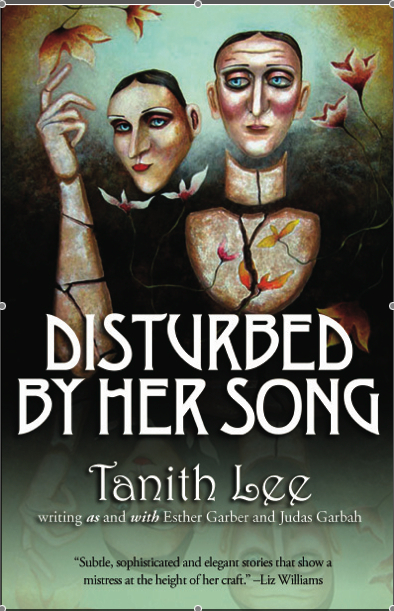

She has just published one of the strangest books yet. Disturbed By Her Song (Lethe Press) collects the magical realist, quasi-historical short fiction of half-siblings Esther and Judas Garber—a lesbian and a gay man—that the heterosexual Lee channeled. Lee has featured gay, lesbian, bisexual and transgender characters throughout all of her fiction—particularly in her now reissued classic fantasy Flat Earth series, which was partially influenced by Oscar Wilde’s fairy tales. (The first volume, Night’s Master (Taleka) is out; the second volume, Death’s Master, will be out at year’s end).

Can you speak about how you met Esther and Judas?

Tanith Lee: The first way Esther made herself known to be was by showing me a grave. Friendships have foundered on less—but then, of course, I wouldn’t presume to call Esther a friend. Nor indeed have I ever met her—or her brother Judas—physically. They are both, I must guess, creatures of my imagination, along with thousands of others. Yet, though my characters always seem entirely real to me, the Garbers (even the evasive, mostly off-stage Anna) have a reality and a communicative presence unique to them. The grave, by the way, appeared in a dream. It was nice clean marble, engraved with only the number “34”—and it triggered Esther’s initial novel via me. From line one of which, Esther was there. Again, not unusual. But somehow she, and he, when they are, are there in a mostly indescribable but insistent, nearly omnipresent way. Judas arrived later than Esther, in fact. He simply made himself known, rather as if standing behind me and to one side of my brain, elegant, laid-back, and demanding of immediate attention. Which naturally he received. It’s always an event to get a Judas transmission. And equally galvanizing with Esther, who so far is also apparently more prolific. (I still await her other known-of novel, Cleopatra at the Blue Hotel).

How is this channeled fiction different from your other fiction?

TL: Essentially, and self-evidently, Esther and Judas both know a lot more than I about some very different things—and I don’t necessarily mean sexual matters; obviously, I’ve written gay fiction elsewhere that is incorporated in my general work. They seem to know, for example, a lot about Egypt, France, even Russia, etc., which, given (where accurate) personal histories, is not odd. It is always however, we find, especially in Esther’s case, a peculiar, time-floating, anachronistic and idiosyncratic take on wherever, and whenever they choose to set their stories—which are, I at least assume, both largely and unsparingly autobiographical, and at the same moment capable of great camouflages and downright lies. Given this, and the particular ease with which I seem able to access their narration, I can progress as a rule very fast and with few halts or internal questionings. I mean, I’m not making it up, am I? And if they are half the time, I really enjoy the exoticness of their falsehoods. Writing a Garber piece from either she or he, although they have, for me, a distinct unlikeness to each other, is a fast ride, all caution thrown to the winds. I trust them (I sense Judas, at least, laughing)—I’ll say then I trust them artistically and creatively—all the way. And here is the biggest difference, then. Elsewhere I have struggled with a few books/stories in which I could not get “The Truth” out of my characters. When I felt them solidly withhold, prevaricate, it blocked the work, until we had it all sorted out. As for outright, let alone Garberesque lying—elsewhere that has sometimes killed a book entire. So, it seems I can’t handle characters who lie—not to others or themselves—but to me. After all, I’m supposed to be the reporter, their scribe. Yet in the case of the definitely dishonest Garber, it seems their flights of fantasy enhance for me their performance. Curious.

Who do you see as Esther’s literary influences? How about Judas’s?

TL: I haven’t any idea as to who/what in literature has influenced Esther, let alone Judas. (She is uninformative there, and he elusive.) I do detect, I think, she prefers short stories. Conversely I am aware she likes some—again shorter—classical music. Debussy. Ravel and Satie come to mind: notably Satie’s Gnossiennes. I, too, like all the above, including orchestral interpretations, but I sense her rather turn her shoulder to my great loves, Rachmaninov, Prokofiev and Shostakovich. We share a taste in painters such as Mondrian, Renoir and Monet. But while we both love the early Picasso, she is decidedly fascinated by his abstracts—to only a few of which, while seeing his genius, I can’t respond. Meanwhile, given your question, I have tried to learn something about Judas’ preferred writing, art and music. But it is like sending a letter to a long-distance acquaintance who simply fails to reply to that specialized inquiry. There is the odd hint in the stories, maybe…I’m not sure.

Your classic series, The Flat Earth, is currently being reissued. It’s a cycle of fairy tales and legends where sexuality is fluid. What can you tell us about that series?

TL: Less fairytales than demon-tales, surely; mythos meets Arabian Nights, etc.: like most of my stuff it came from an instantaneous idea, a moment of sidelong thought—on this occasion a phrase in a word game: “Go nowhere fast on a horse that fades.” The first book flew forth with no pause. And again, as with most of what I do, the first book and its followers came with their own environment and ethos, and aspect of which happens to include the premise that almost all Flat-Earthians are bisexual, if perhaps with some individual biases in one or more directions. Of course, the Flat Earth isn’t the only venue in which multi-sexuality has flavored the works of Lee.

Have you received negative feedback from readers or critics, in respect to the sexually mature and diverse themes in your adult fiction?

TL: Perhaps strangely, no—or nothing I personally encountered and recall. I suppose that I don’t read that many reviews, and though I enjoy enormously the favorable ones, the ones that hate my work have every right to hate it, but their hatred is irrelevant to me. I only inwardly gripe a bit when they completely misunderstand what the book was saying or meant to do. I don’t mean by this if they do know what was intended, and merely think I haven’t managed to achieve it—again, that’s their opinion, and fair enough. The problem is where they decidedly reckon, and go into print to say so, that I was, as it were, aiming to hit the red target, while I know I was aiming for the green. One other gripe is where my work is misquoted, using word combinations I would not have penned. It has happened. Readers who write or speak to me normally do so with courtesy, and often praise, and where a reader has liked my work I’m frankly thrilled. I revel in my trade, and if someone gets something from my storytelling, and lets me know, it’s a beautiful bonus really beyond my deserving. I suspect readers who loathe my various takes on life, the universe and all that, just very sensibly avoid them, and me.

While you are not explicitly a “political” writer, many themes do emerge from your—and, indeed Esther’s—work. (Sexism, anti-semitism, aging, and racism all are addressed in “Disturbed By Her Song.”) What are your social/political passions?

TL: Indeed, as already said, I’m not political. Except sometimes on a page (i.e., the French Revolution) the political arena is to me, as someone once said, usually a false theater parading false wrath, false joy, false truth and false lies. I don’t have social/political passions, as such. Of course, I enragedly shout at the radio or TV—have always done so, even when young. And I detest all the evil things you have listed. But primarily I am a storyteller, and one who is eternally intrigued by and enamored of the human animal. Free of all chains (for good or ill) when I write, I am willing to take on almost anything head-and-heart first. Even hidden under contrary character carapace (as when writing of a happy or—worse—righteous mass murderer), my preferences must always be there. To me, all the blind and ignorant cruelty that wanders the world in so many petty and powerful guises, is one of the biggest wasters of human time known to Man—except, inevitably, for the use it offers most creative artists. Esther and Judas, however… I think she spends very little time on this, even in her work. Racism and sexism appear often, without much if any added comment. They are seen as facts. She herself accepts the gibes about her race, and she accepts the male rape of her—only in order to survive, or simply to get on with her own assorted tasks and obsessions, then dismissing any rubbish, it seems, carelessly and at once. Esther really isn’t going to make a stand—or she hasn’t yet. Only her characters review the horrors, sometimes, briefly (as in [the story] Death and Maiden). As for Judas—heaven knows. I predict he’d just walk out if one tried to inspire him to a proper passionate political enthusiasm. “Change will never really happen. People are always the same. Let’s get on—” would be my instinctive paraphrase of his reaction.

Back in the 70s, you were a part of the brigade of female authors—including Ursula LeGuin and Marion Zimmer Bradley–who broke the glass ceiling of genre (SF/F/H) publishing. What do you see as the differences between now and then? Has progress been made?

TL: The politics of the world, let alone the publishing world, have never been that clear to me—I can be impatient. I do obviously know that women have always had trouble getting ahead in any important field, literature included. I wasn’t, myself, aware of breaking through a glass ceiling—and anyway the justly prestigious LeGuin and Bradley were some years ahead of me in publishing fame. All I knew was that, after almost a decade of indifferent rejection, finally in 1974/5 I could write for a living instead of all the alternative deadly things I’d felt forced to do. Recently, alas, with today’s climate, I have apparently been outlawed by those large “major” companies through whom, for over thirty years, I’ve previously had quantities of work. I don’t entirely understand that, either. But naturally I hope that things will improve, and that all the very good young and new writers I have glimpsed around me will prosper, female and male together.

Photo: John Kaiine