Michael Klein: Still Living

Author: Tony Leuzzi

April 7, 2011

“…. Writing should never be mawkish or sentimental! Why bother?”

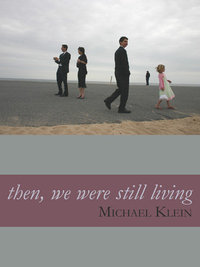

Poet Tony Leuzzi interviews current Lambda Literary Award finalist Michael Klein about his latest collection, then, we were still living (GenPop). Among other things, they discuss what Klein calls the “hypocrisy of death glorification,” 9-11, and the difference between older and younger poets.

TONY LEUZZI: Congratulations on your being named one of the finalists for the 23rd Annual Lambda Literary Award for Poetry! then, we were still living is a fascinating book that deserves the recognition it is getting. I was wondering if you could talk first about the significance of the title.

MICHAEL KLEIN: I really wanted to name a book with a phrase that could be put in a sentence somewhere but not necessarily in the beginning—to give a sense of this dangerous and transitory world of the last 20 or so years and signal, too, the collective—the “we” as opposed to the “I”—which I have been, it occurs to me too long in the grips of. It’s a title that acknowledges collective survival but also a kind of awe at that survival.

I also wanted a title that didn’t sound like a title—to quiet it down—because this is a book that deals with a lot of sad things and I didn’t want to shine the harsh light of the obvious on it. And, of course, it’s a line from one of the poems, as well, which (and I’m a traditionalist here) is where I think any title of a manuscript really is. Try to find at least one line that sounds smart!

TL: This is your second book of poetry in 17 years. 1990 tied with James Schulyer’s Collected Poems for the 6th Annual Lambda Poetry Prize in 1994. What are some significant ways in which then, we were still living differs from that earlier work?

MK: And, once again, I am a finalist with James Schulyer who is still dead! 1990 was my MFA thesis, first of all, so it’s young and it’s almost entirely autobiographical. then, we were still living touches here and there on the story of my real life, but many of the poems were channeled (and for a few of the poems, I mean that literally) and, like the “we” in the title, it was really time for me to look out and see and report on the much larger world and where I live in that world.

Also, it is a book informed directly from the events of 9/11 and looking at a world that is more and more somewhat fixated on gazing into the abyss. And, of course, the way the poems in the new book fall on the page is very different. I wasn’t nearly as concerned with making stanzas (though those kinds of poems are there) as much as I was in making these sort of fragments that go in and out of the imagined and the real. In many of the poems, I heard two voices as opposed to one.

TL: In the interim, you wrote two memoirs—Track Conditions (1997) and The End of Being Known (2003). Do you see yourself primarily as a poet or as a writer who writes, among other things, poetry?

MK: I’m a poet. Everything I write is informed by that impulse to stare language down. Poetry is how I came to the art of writing and the books of prose were written only because I had nothing to say that seemed like it was going to be said or had to be said in poetry.

Track Conditions and The End of Being Known are books of prose because I didn’t want to write poems about horses or poems about how confused and lonely I was at not being in a committed intimate relationship. Those subjects, in a way, just seemed too—what, obvious?—for poetry.

And I wanted to teach myself to write prose because I don’t have the patience or stamina for poetry all the time. I write many things—critical things as well as poems and these short lyric essays—and they all come from the fact that I decided a long time ago to take on poetry. It has always been more of a challenge to me than prose, even given the fact that I basically taught myself how to write prose.

TL: In what ways does your approach to writing memoir differ from your approach to writing poems?

MK: The inhabitance, or haunting, is different. Memoir is fixed at a reckoning point of one’s own being in a way that poetry doesn’t necessarily have to be. And what I see in my mind when I am writing one or the other is very different. I actually see language with poems and place with prose. Also, when I attempt a poem, I think away from my life as much as I think from my life, if that makes sense.

TL: In many of the poems in then, we were still living, you explore the politics of love and loss, as well as the suffering that comes from loneliness, desperation, and violence. Yet the poems are never mawkish or sentimental. In fact, the control and detachment with which the voice recalls and explores emotional turbulence lends these poems their power. I see this particularly in “The Ranges” and “My Brother’s Suitcase.” Can you discuss your narrative control and detachment with regards to these poems?

MK: First of all, writing should never be mawkish or sentimental! Why bother? There’s enough of that in the world. I’m always sort of amazed that any of that kind of writing actually exists. It’s like bravery— although bravery is at least a better word.

People used to tell me after readings about how brave I was and to me, it’s not even a choice. You don’t say, if you’re an artist, I’m going to be a brave artist— i.e., the act itself, of any art, is bravery. One enters completely alone into a void with a mixture of terror, faith and urgency.

As for detachment: it really is the only way to see a real truth, which is why in memoir, for example, it makes no sense to write one about something that just happened to you—no matter how tragic: which always just screams, write me, write me anyway.

I’m reading Darin Strauss’s amazing Half A Life, about an incident that happened when he was 18, in which the car he was driving struck a girl on a bicycle and killed her. That book took him, well, half a life to even approach. I’m a romantic, so anything with which I’m intimately involved is always skewed because of it and the distance makes you see it in the world—i.e., why it’s important to you—beyond the simple fact that it happened to you or is, objectively, a story worth telling.

Those two poems in particular, “The Ranges” and “My Brother’s Suitcase” are about, obviously, my brother’s death and my father’s death and they are poems about the weight of absence—not their not in the world anymore absence—but, in “The Ranges”—the absence of not being willing to love something or someone because there’s only one kind of loving and in “My Brother’s Suitcase”—the physical absence of something inside that suitcase that makes it even heavier to carry.

My cat—a leap, but bear with me— Caleb had to be put down last year and my boyfriend, Andrew and I were just destroyed by it for a few months. He was—like every animal that lives in a human household–extraordinary and funny and beyond adorable. When he was put down and Andrew walked home after leaving the vet’s office and Caleb dead on a table, the carrier he had brought him into the office with had to be carried home without anything inside it. There was a whole life in that emptiness that had just been taken away. And so, it is/it was with my brother’s suitcase: his whole life is in there, in a way, so it will never belong to anyone else.

“The Ranges” is really a very strictly narrative poem and I wanted to talk about how dumb a father can be toward his own queer, tow-headed, sports-hating kid—but in a way that was as fragile as love is or pretends to be. I never want to turn people in my own life or past life into characters. Even if they drive me crazy in some way, I want to see them as whole people and reveal them with a sense of wonder, too.

TL: A good number of the poems in then, we were still living reference 9-11 and the war in the Middle East. What drew you to these subjects and how do they relate to the larger themes of the work?

MK: What drew me to those subjects is the same thing, I suppose that draws the world to those subjects: its reality and conspiracy all at once. But, more importantly, I think this is the story of living at this moment and has been for many years. The world is on fire and I’m very surprised, in a way, that it’s still even here. So I’m drawn to those subjects because I want to live against the incredible amount of death glorification and hypocrisy I see all around—in this country and in the world. We’re here to live and it sounds so simplistic when you put it that way but life, actually, is a pretty simple thing when you take people out of the equation!

TL: A poem-by-poem reading of the book also reveals your concentration on certain words. I’d like to mention a few of these words and have you respond associatively to each of them:

World – Point

Always – Horizon

Life (and its cognates) – Duende

Then – Entry

TL: In a prior conversation, you told me your poem, “Five Places for Sex” has drawn more comment from readers than any of the other poems in the book. Can you talk about this poem and why, ironically, you were not going to include it?

MK: I wasn’t going to include it because it’s funnier than anything else and it’s in a totally different sounding voice. O’Hara and Tim Dlugos a bit and some other poets I love are very much influences here. I was going to write a book—and I always say this at readings before I read the poem, it’s become a kind of shtick, forgive me—called “50 Places For Sex”, but I could only come up with five.

And I wasn’t going to include it—in all honesty—because Chase Twichell told me not to. Then, after about another year of revision I saw that if I placed it in the right way—in the middle, basically—the front half and the back half of the book could act as wings and then it just worked. It’s the happy, nostalgic, STILL LIVING part of the book, in a way.

TL: “Vaudeville” is one of my favorite poems in the book. Can you discuss this poem as well?

MK: Interesting. It’s probably the newest poem in the book, and completely weird how it came to me. My grandfather was a somewhat well known vaudevillian (he really did make the song “The Red, Red Robin comes Bob Bob Bobbin’ Along” famous and he played the Palace, etc., etc.).

He was also a raging drunk and died from the disease before he hit 40, in Atlantic City. And, I knew that Alfred Hitchcock (my mother told me this, so maybe it isn’t true) wanted to make a story about his life, starring Jack Carson.

That’s all I had going into the poem. And then, as it is with most everything I write, what I thought I wanted to say took a left turn and I just followed along with some language that would still keep the poem interesting to me.

TL: Overall, I was surprised by the formal variety here. You are quite versatile with lineation, and some of your lines are deliciously long, while others are tersely short. Who are some of your influences in terms of lineation and line shape?

MK: I never think of actually being influenced by someone’s form, or how a voice dictates a design because I am always listening to line which, if it’s a line I wrote/am writing, has a life of not being influenced at all. I try for that and I am always willing to have content dictate form. The only pleasure I get from form dictating content is with music.

But when I write I really want the subject to move the syntax and regulate the breathing. It’s only when I go and read people like Wayne Koestenbaum and of course, C.K. Williams, who have both really excited me when I am inside those long, rhapsodic lines or Creeley with those perfect short lines that were invented, in a way, by William Carlos Williams, that I realize something—some relationship to the actual measure of a line—has entered me, even when I resist it.

And so, it always feels unconscious. Frank Bidart’s lines are incredible, but I could never write like that. I don’t think like that—the almost interrupting line and the typography which is so visceral and scary in a way.

TL: I was really impressed with how you exploit punctuation for interesting effects. Your use of the dash in “The Movies,” for instance, really guides and transforms one’s reading of that text in surprising ways.

MK: Alan Dugan once told me when he read 1990 in manuscript form that the dash was “sentimental” and I have not been taking his advice ever since.

TL: 1990 was dedicated to your friend, Jean Valentine. There’s no question that her influence can be found in some of your work, especially in the more concise poems like “What We Look For” and “Anyone’s Child.” In what ways do you feel you have absorbed her as an influence? In what ways, however, do you feel your work marks a significant departure from hers?

MK: Well, it departs from Jean’s work in a lot of ways. I’m influenced much more by the sound of her poems than I am by their subject matter—even though, of course, I completely adore her subject matter: that dream world, her acknowledgment that language fails with the first syllable, that poetry is always, always an attempt at something and never the thing itself, the world itself.

We also have very different concerns, I think, as writers, but we also have a very similar sense of the power of mystery (or so I like to think). Funnily enough, I’m rarely compared to Jean—nobody is ever really compared to Jean because—and of course, this is her genius—nobody sounds remotely like her, even when they try to sound like her.

TL: You are nominated for an award alongside two long-deceased poets of considerable stature (Schulyer and James White). You yourself are not of their generation, which might be called the first wave of Post-Stonewall “gay” literature, but you are also not in the vital crop of younger gay-identified poets beginning their careers. In what ways do you see yourself situated between these two groups?

MK: Well, there are some vital crop middle-aged poets, too!! Mark Doty, Henri Cole, David Groff, David Trinidad…

TL: I didn’t mean it that way! Of course there are many exciting and important gay poets who have been writing professionally for the past 20-30 years! (Laughs)

MK: I know. The sad fact is that a lot of them are dead: Tim Dlugos, David Craig Austin, Melvin Dixon, my own brother who was a poet as well—all those guys are of my generation. And, most importantly, I’m still of the generation of poets who didn’t think and still don’t think so much about having a “career”.

A lot of younger poets I think want to be known for who they are as agents of ambition rather than poets who are really on to something complex and game changing. It’s easy to blame the commoditization of art, of writing, on MFA programs, but I think it’s more than that. It’s the world at large: what can I get as opposed to what can I give.

I’m invested in an art form, not a product. And, as you can see, it takes me a long time to write a book of poems or anything else. So, of course, I’m not getting a lot of return on my original investment!

TL: Finally, if you were asked to make a shortlist of the three most influential poets upon your work (excepting Valentine) who might they be and why?

MK: Impossible. Not just three. I have to give you six living and three dead poets, if that’s okay. That’s always such a hard question to answer because I’m easily influenced by the poems I like. The people who have lasted; who I keep reading, who I want to always be reading as long as they are writing poems and who I will probably always be influenced by because I am listening harder to what they have to say than what anybody else is saying would have to be the living Louise Gluck, Chase Twichell, Mary Ruefle, Bruce Smith, Frank Bidart and Claudia Rankine and dead poets would be James Schuyler, Frank O’Hara and Rilke.

And I love many non-Americans: Adelia Prado, Tomas Transtrommer, Miroslav Holub, Paul Durcan.

Claudia Rankine’s book, Don’t Let Me Be Lonely is so important to me and so is Frank’s In the Western Night and Louise’s Ararat and Mary Ruefle’s newly released Selected Poems which was the best book of poems I’ve read in about two or three years.

The interesting thing that distinguishes the living from the dead in this list, to me anyway, is the fact that I would consider the living poets to be more dialectic which, for me, is the cadence of living an examined life, while the dead poets are—I don’t know, less dialectic because of their humor (apart from Rilke)—but freer in a way with the line, influenced more by visual art—how they see form in the world.