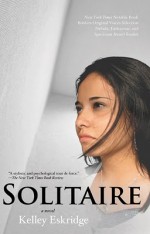

Kelley Eskridge: the Invention of ‘Solitaire’

Author: Diana Denza

March 10, 2011

“I’m fascinated by stories of identity, of choices and consequence and big feelings”

Novelist and short story writer Kelley Eskridge dishes about her reissued science fiction novel, Solitaire (Small Beer Press), what it’s like to live with another author (Nicola Griffith), and her ideal literary three-way.

What are you currently reading?

I’m about to dive into the advance reading copy of Queen of Kings by Maria Dahvana Headley (Dutton) (a friend’s first novel, which is always a happy occasion), and after that I’ll be reading the draft of my partner Nicola Griffith’s new novel (so excited!).

Solitaire was your first novel. What authors or books inspired the creation of Jackal’s world?

Pretty much every book I ever read and loved. They didn’t inspire me to construct this particular story: they inspired me to tell my own stories better. They still do.

Every character I’ve ever imagined myself being (or being with), every moment that’s made me laugh or cry or think, every story that has ever given me comfort or turned me inside out — those books and movies and TV shows inspire me to tell my own stories as deeply, and with as much power and truth and skill, as I can. I think all good writers inspire each other in this way.

It makes me want to shriek when putative writers tell me earnestly, “Oh, I don’t read. It gets in the way of my creativity.” That’s ridiculous and worse, it’s counterproductive. I have never met a real working writer who subscribes to it. We don’t just learn from each other, we feed each other’s desire to be part of the great ocean of human storytelling. We make each other better.

In the novel, main character Jackal is in a lesbian relationship with a woman named Snow. How important do you think it is for LGBT teens to read about loving gay and lesbian relationships?

It’s important for all human beings to read about loving relationships of the kind we might want to have someday (and to see them in the movies, and on TV, and in the coffee shop, and on the bus….).

Straight white folks get this kind of reinforcement a lot more than the rest of us in this culture, so loving queer relationships take on more freight. It’s essential that art include all of us.

If we don’t see ourselves reflected in the stories around us… well, that’s just one more way of being made marginal, invisible. On a particular level, culture is story, and if we aren’t in the stories, then we sure as hell aren’t in the culture either.

What was the first novel you read where the main characters were involved in a lesbian relationship?

Rubyfruit Jungle. Whatever gods there may be, bless Rita Mae Brown.

Jackal was trapped in virtual confinement for 6 years. For many of us, that’s a terrifying notion, especially in a world where we are connected to each other around the clock via social networking. Why did you decide to explore this theme and what do you think readers will take away from Jackal’s experience?

I’m fascinated by stories of identity, of choices and consequence and big feelings. Stories of how we become ourselves. I find those stories everywhere, and I have written many of them myself. What I don’t see as much is the exploration of solitude, and the examination of alone versus lonely, that is a conscious theme in Solitaire.

I wrote the novel in part because I wanted to read a story about that. I wrote fairly deeply about this recently for The Big Idea series at Whatever, and anyone who is interested can read more here.

Jackal’s time in VC was described hauntingly, but it in a relatively short chunk of space. Why did you devote so little time to her actual confinement?

Because less is more. Reading is interactive. As a reader, I bring my own experiences and values and feelings and questions about life to every book and movie, and I’m looking for a way to connect that’s meaningful to me.

There has to be space for me in the story for me to do that — to hook into that story and share that experience, for at least that moment in time. If I’m not engaged that way, I’m not interested. I set aside a lot of books for that reason. For me, the power of story is to experience different choices, different worldviews, different lives with all their moments of love, hope, fear, rage, joy.

If I’ve done a good job in Solitaire — if I’ve chosen the specific details that make Jackal’s experience clear, that fire the reader’s imagination and take her along for the emotional ride — then I don’t need to chronicle every minute of her confinement. The reader will do that herself, with the powerful engine of her own imagination, and she’ll feel it a lot more deeply that way.

Looking back, would you change anything in Solitaire? Why or why not?

Nope. It’s not perfect, but I don’t need it to be: I need it to be true, and I think it is.

Solitaire first came out in 2002. How has the queer literary landscape changed since then? Do you think it would have been more difficult for Solitaire to be published now than in the early 2000’s when major publishers sought to increase their output of gay books?

I find it amusing to consider Solitaire as part of some publishing initiative to “get more gay.” No, I don’t think I’d have any more trouble now. My editor bought the book because she loved the story; HarperCollins approved the deal because they thought it would do well critically, and they thought it would sell.

Frankly, no one gave a toss about the relationship. There is a lot less active homophobia in major publishing these days that there was when the afore-blessed Rita Mae Brown, for example, was out pitching Rubyfruit Jungle, or when Barbara Grier and Donna McBride were setting up Naiad Press because no one else would publish stories about loving lesbian relationships.

Major publishers do not care who your protagonist sleeps with, or whether her expression of self is genderqueer, as long as the book is good. Of course there are individual people in publishing who are homophobic and racist and misogynist and bedeviled by all kinds of other bias, and sometimes those people will be in a position to reject a queer book because it’s a sin, damn it, and it shouldn’t be allowed. That happens at the grocery store too.

Solitaire is being adapted into a movie. Who would you cast as Jackal and Snow in your ideal movie scenario?

Well, that’s tricky because the screen story is very different — as in, pretty much totally different — from the novel. I’m fine with that: I’m the lead writer on the screenplay now, and I love the story we are telling.

There are essential concepts of the novel in the film, of course (they wouldn’t need the book otherwise), and at their emotional core the book and the movie are definitely siblings. Besides, I find that the writer is often the last to know who is right to portray a character.

Remember the fuss Anne Rice made about Tom Cruise being cast as Lestat in Interview With the Vampire? And he was brilliant in the role.

You live with another author. Can you tell us what that’s like? Do you have writer’s block together? Do you have separate writing schedules? How do you both manage that relationship?

It’s a serious joy to live with Nicola Griffith. I don’t know how writers manage without a trusted reader and editor and truth-teller, and our work as writers is one of the deep foundations of our marriage.

We’re very different as writers in terms of process and product, so if we ever do come up against a wall at the same time, it’s just timing. It happens; when it does, we try to help each other, the same way we try to help and support each other’s work in every way we can. We are separate writing creatures, but there’s no doubt that we are inextricably bound to, and in, each other’s work.

I can go on at length about what it’s like to live this way, and in fact, I already have. Several years ago, Nicola and I were approached to contribute to an anthology called Bookmark Now (Basic Books). The editor, Kevin Smokler, was looking specifically for a joint essay from writer-partners about their relationship.

We were, I believe, the third couple he approached: the first two couples fled in terror at the thought of revealing the intricacies of such a thing. We just thought it would be fun, and it was (it was also, interestingly, our first collaboration). The essay is called “As We Mean To Go On” and is available on my website for anyone who wants the 5,000 word answer to the question.

If you could have a literary three-way with two other authors (sans your partner), who would you choose? Why?

Hah. I assume we’re talking about rolling around in the book-mud, as opposed to actual sexual congress accompanied by poignant metaphors and crackling dialogue…

I’m imagining a collaboration with Stephen King for sheer virtuoso storytelling and amazing expression of character, and Shirley Jackson for the precision and restraint, the consummate hand of less-is-more.

Me, I’ll be the big-feelings part of the mix, the exuberance, and the power and joy of being queer.

Photo: Jennifer Durham