How the Words of Nikky Finney Help Get Us Through Breaking Up & Breaking Down

Author: Candice Iloh

September 24, 2015

1

June 18th, 2015, you are almost finished packing what is left of your things, in the apartment you and your partner once shared, and prepare to leave for the last time. The walls, colored with the most vibrant hues of mustard yellow, mystic turquoise, and lavender blue are also clad with art the two of you had collectively acquired and family photographs picked up along the way before deciding to put both of your names on a lease. +The two of you built this. These close walls of your fourth floor walk-up studio apartment space were transformed from a cheap broken down flat to one of the most beautiful things you created together. The stale fumes remaining of a previously evicted tenant gave way to the recurring aroma of your fiancé’s unmatched skills in the kitchen. As you remove the pieces that were yours and stuff your books, shoes, and clothes into every bag, you can find you also remember that these walls are thin.

By now the neighbors can probably imitate each of you. The deep hum of your carrying voice and her soft outbursts in song. Your sounds had become the building’s norm: the ranging bellows of the late night, frequent slamming of the doors, or your cries for attention on any given day. In this Brooklyn apartment where you fucked and fought more times than you can remember, your voice has grown tired of begging to be something worthy of response. Weary of the same arguments and same requests, you are packing your things and moving on from the first woman you had ever considered spending the rest of your life with. No longer can you stay; only dead fumes remain where breath once was warm and alive.

I dress up as the woman I could never be

in real life, then walk the runway before our

(former) bed, slowing, near the sailor’s trunk,

at the church bench, one long curtsy near where

her soft owling mouth would ease into

the headboard, a waterfall of hands, ghost clap; (“Shaker” 22-27)

2

You walk onto the campus a new MFA student, your body aching from shifting all that you own to a new borough and now the four-hour bus ride to Boston. Prior to the trip, the faculty asked you to read so many things before arriving but finding a place to live had monopolized your time. You drop your bags in the room that will be your home for this week of residency and exhale. This is the first room after two and a half years you get to claim to yourself. You soon meet two women in your cohort who are new like you, one Korean, and the other Hispanic. Quickly you cling to them like the last piece of clothing you’ve preserved after the passing of a late cousin. You wonder if you will be the only queer black girl in your class. Of course, you are. You already know you were something peculiar and something of interest at the same time. Who could miss the bald brown girl who retreats to her dorm room every night instead of trying to fit in at the campus’ local bar after seminar?

You don’t feel so different and so in need of those two women until one of your first classes–one of the only two that would address poetry. Your language. Everyone in the class raves about a poem you think is complete shit and void of the world you exist within. But the author is an ancient dead white woman who had followed the instructions of a villanelle and therefore it must be brilliant. They call it classic. You immediately become the target of the class when you raise your hand and identify the poem’s lack of creativity and lack of challenge. Suddenly you become aware of the thing you were warned would happen: becoming the trouble-maker for disagreeing. For opening your mouth to push back against a thing the majority has already deemed more worthy of space and breath.

No. Not this time. This time she wants what she was once sent for left whole, just as it was pulled from the sea, everything born to it still in place. Not a girl any longer, she is capable of her own knife-work now. She understands sharpness & duty. She knows what a blade can reveal & destroy. She has come to use life’s points and edges to uncover life’s treasures. She would rather be the one deciding what she keeps and what she throws away. (Finney, 3)

3

You are back in New York and teaching a high school class on race, gender, and sexuality with a straight white woman and a gay black man and one of your students sees the word asexual on the board, smiles and screams, “That’s me!” Another asks to read something she has written in front of the class: the requirements for dating a girl like her, written after Junot Diaz’ How to Date a Brown Girl. The first requirement: that you, like her, must be a girl too. One finds the language to describe herself, where alienation once lived, and now has a new way to assert it. Both discover ways to own their personal experiences in this world that tells them they are powerless or simply other.

“The sight and sound of them does nothing to change her mind.” (Finney, 4)

4

This is the part of your life where you technically no longer have a home and technically are not working but have gotten on a bus to Philadelphia to be with your sisters. Most of them brown and queer, you all planned this because you said it is what was needed. To see each other. To embrace each other. To hear each other speak. You needed the space to walk the grounds of this Airbnb braless, bare, and shame-free without fear of censorship nor muzzle. The weight of the world dropped on the floors here and becoming vapor as you laughed together, cooked for each other, and held hands to affirm your past and present selves.

Unlike the two other times the group had done this, no actual plans were made before you arrive but everyone just begins talking to each other. You discover everyone’s life is in transition. Everyone needed the space to say what they wanted without it being deemed too much, too angry, too afraid. Sexual preferences, a conversation. Community work, a conversation. Boundaries a conversation. The weekend blooms into two days of 14 women using their voices to create the spaces unquenched elsewhere.

“The girl is still there, still breathing, still camped out/at the unbroken glass, with a toothpick-size shadow/of resistance balanced in the flush of her lips” (“Thunderbolt” 51-53)

5

Before all of this, you meet Nikky Finney for the first time. Several other women who look like you line the aisle to ask her do you think it’s possible to… and what can us black women do… and… how do I… and should I also be… After a while, she interrupts the avalanche of doubtful questions that mirror exhaustion–exhaustion from not being heard, from not being seen, from feeling that you must always be strong and carry everything silently and says, “Forgive me, sis, but we don’t have to carry everything. Your words are enough. Your words are enough if you work hard enough on them. What am I to do but go out into the world and open my mouth?” This time you stay to buy and have her sign the book.

Lily of my Valley, “odds ain’t the best they say”. Did you

hear ‘em talkin to me that way?

Dropping her voice down to a whisper, she stands like a

black beam against the wind, both arms akimbo; (“Time” 133-137)

6

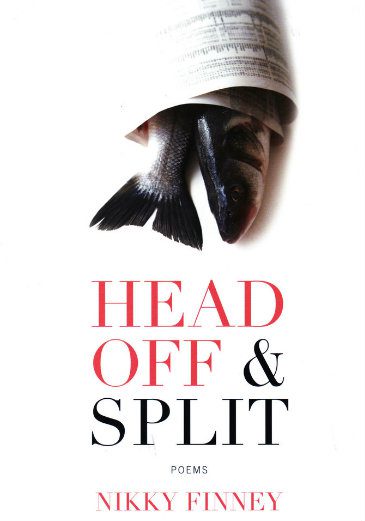

Finney’s Head Off & Split teaches us to identify things in ourselves and others, thus helping us decide how to navigate through the world. Our wants. Our beliefs. Our spirits. In each poem, you are experiencing the subject’s several identities. But the through-line is Finney’s voice. Her voice–your voice–becomes the most important thing. The thing that gives you permission to exert control and power over things that constantly challenge your existence, your peace, your confidence, and your ideas. You see that if you can truly examine these people–these experiences–and find yourself, find the importance of you talking back to your own. You can ultimately decide that it’s better to speak than to watch yourself be manipulated and crushed into silence.