Appreciations: Derrick Austin’s “Summertime”

Author: Thomas March

August 31, 2016

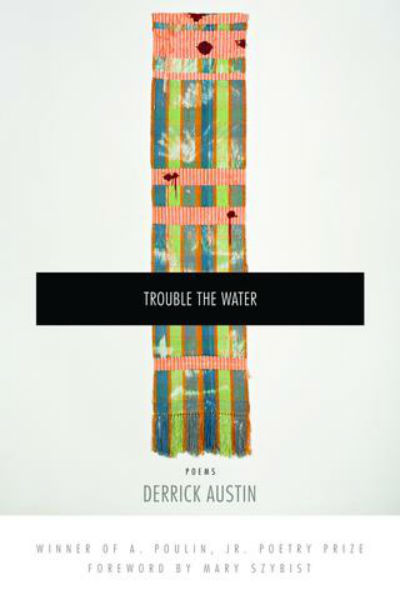

Every month, “Appreciations” looks closely at a poem or poems from recently-published books by LGBTQ poets. Each column celebrates new work by appreciating some of the figurative and formal achievements of these poems. This month’s poem is Derrick Austin’s “Summertime,” from his recent collection Trouble the Water (BOA Editions, 2016).

“Summertime”

A pipe burst somewhere. The record kept turning

Porgy and Bess. Granddad sang the old blues tune.

I told him my name. The water was burningwhen we went to the coast, green and churning

like collards in the kitchen. It was June.

A pipe burst somewhere. The record kept turning.He took worm-colored pills at ten in the morning,

sometimes he wandered off. I’d find him at noon,

streets away, calling my name. Water was burningfrom Gulf Breeze to Grand Isle, the Gulf swirling

like vinyl. Egrets blackened the bayou.

A pipe burst somewhere. The record kept turningwhen we watched the news in the nursing

home: men in white scanned the dunes.

I told him my name, that the water was burning.He looked through my eyes and sang fish are jumpin. . .

I said his name, washed his feet, left the room.

A pipe burst somewhere. The record kept turning.

I told him my name. The water was burning.

Derrick Austin’s “’Summertime,’” from his richly spiritual and sensual new collection, Trouble the Water, is a lovingly stark but gentle poem about the painful reality of a loved one’s dementia. The song that the poem’s title refers to is one whose repeated lyrics reinforce its sense of comfort and hopeful longing. Similarly, the form of Austin’s poem, the villanelle, is vigorously iterative and provides an especially effective means for puzzling over and through a challenging emotional reality. Although a villanelle can just as easily be playful, this poem’s repetitions and significant revisions to its refrains work to affirm and to stabilize as much as to describe. The poem is set during the speaker’s visit to his grandfather, who lives in a nursing home, and describes the paradoxes of a particular kind of dementia—the living outside of real time and yet so fixedly in another time. And in doing so, it embodies the grace of maintaining whatever connections can exist while someone you love loses contact with the world.

The poem’s first stanza establishes the grandfather’s limited connection to the world around him, as well as the speaker’s calm, determined presence within that reality. The stanza’s emphatic and deliberate pacing, with its three caesurae and one end-stopped line, helps to structure the stanza as an inventory of sorts. The momentary lingering that each stop enforces, along with the near absence of modifiers in these sentences, suggests a calm dispassionate documenting of the state of things as they are. This simple but stark reality is one in which the crisis of a bursting pipe is unremarkable. That the song keeps playing, as Granddad sings along, is an indication that Granddad’s awareness is limited and in at least some way impenetrable. When the speaker reports, “I told him my name,” the neutrality of his tone allows the painful irony of the scenario speak for itself. There is no weariness here, no lament, just a response to the grandfather’s real and present need for this simple but essential information. It is a response that closes the distance between them as much as possible; it demonstrates the speaker’s willingness to accept his grandfather’s reality as it is.

The enjambment between the first and second stanzas creates a fluid continuity between this moment in Granddad’s room and the speaker’s memories of earlier, if seemingly only slightly better times. Even as it describes a hot, tumultuous summertime sea, the simile in the memory of the water at the beach as “green and churning/like collards in the kitchen” evokes a domestic association that contrasts with the institutional setting of the nursing home. With only two repeated rhymes to work with in a villanelle, it is a challenge to choose rhymes that offer choices in diction that seem organic while also adhering to the scheme. In Austin’s poem, the rhymes (and slant rhymes) achieve that sense of unforced appropriateness, but even beyond that, they do the additional work of mirroring the contrast between action and stasis that permeates this poem. The poem’s “a” rhymes are mostly participles that suggest action (“turning,” “burning,” “churning,” “jumpin’”), while its “b” rhymes are static nouns that mostly describe circumstances, in space or time (“June,” “noon,” “bayou,” “dunes,” “room”). One of these rhymes marks the end of this memory, as the speaker recalls the simple fact that “[i]t was June,” after which the return of the first refrain, now end-stopped, emphatically reasserts the poem’s present moment, in which action prompts no reaction.

The more immersive return to the past in the next two stanzas swiftly traces Granddad’s decline. The “worm-colored pills” could not prevent him from “wander[ing] off.” This physical disappearance is the precursor of the more permanent one to come. From within this one, though, he can reach out for his grandson, whom he still knows by name. In reporting Granddad’s “calling [his] name,” the speaker lends his grandfather’s demeanor a heartbreaking helplessness. Not simply softer than similar words like “yelling” or “screaming,” “calling” implies an intended recipient. Even from within his confusion, he is searching with purpose just as much as his grandson is. The variation in this version of the refrain, with someone else saying the name and with different purpose, lends new significance to the other instances of the speaker’s reminding his grandfather of his name. Just as this act of literal searching and finding makes the later efforts to connect so poignant in their limitations, reminding Granddad of his name becomes more clearly an attempt not just to connect but to comfort. The transition into the next stanza symbolically reflects the very destruction happening in Granddad’s brain. Here the fact that “water was burning” has apocalyptic echoes, and the descriptions of the hurricane itself suggest danger and destruction. The water was “swirling,” and wildlife took cover, as “[e]grets blackened the bayou.” The return of a refrain in the stanza’s final line begins a transition back to the nursing home, where the grandson once again attempts to connect his grandfather to the rest of the world, as “the record [keeps] turning” in the background.

The transition into the fifth stanza is not only from the outdoors to indoors—there is a shift in Granddad’s relation to what happens outside his room. He and the speaker are “watch[ing] the news” together, observers of the hurricane’s aftermath, filtered through the medium of television news. Watching, of course, is not the same as seeing, as understanding. In this stanza’s refrain, the speaker is once again telling his grandfather his name, but he is also trying to describe for him what they are seeing on TV; here, the reference to the “burning” water becomes a way to explain the chaos and tumult of the storm. In its neutrality, it communicates an acceptance of that which is beyond his control, both the storm itself and his grandfather’s limited understanding.

The quatrain that concludes the poem embodies acceptance and grace. When he recalls, “He looked through my eyes,” the speaker is referring back to his own role in explaining this news to his grandfather but also suggesting, if “through” takes on another meaning, his grandfather’s non-comprehension, even his inability to recognize who either one of them is, as he continues to sing. The ellipsis that concludes that first line functions in several possible ways. It might simply stand in for the rest of the song’s lyrics. It could signal a shift in time—returning to the present and implying that the episode of watching the news together occurred in the recent past, not during this visit. Or it could be a simple interruption of the pattern. Whatever his grandfather has lost or become, the speaker’s saying his name demonstrates that it’s important to remember who he is. Before he leaves, the humble gesture of “wash[ing] his feet,” is a sign of both care and respect, regardless of whether either can be recognized for what they are.

The concluding refrains, appearing together now, recreate the emphatically deliberate cataloging of reality that is so remarkable in the first stanza. But there is a critical difference now. These lines occur as the speaker departs, leaving his grandfather to whatever comfort the record can provide in its continuing turning. The speaker can accept the reality that this visit presents. But the poem offers a reminder that regardless of whether love can be received if it isn’t recognized, it can, at least, still be given. Having been present with his grandfather to the extent that it’s possible now, the speaker in the end is free to feel the impact of his grandfather’s steady disappearance. The emotional response to seeing his grandfather is no longer deferred, and the burning water can now suggest the welling of tears.