Revisiting the Andrew Cunanan Mythology

Author: Edit Team

August 17, 2017

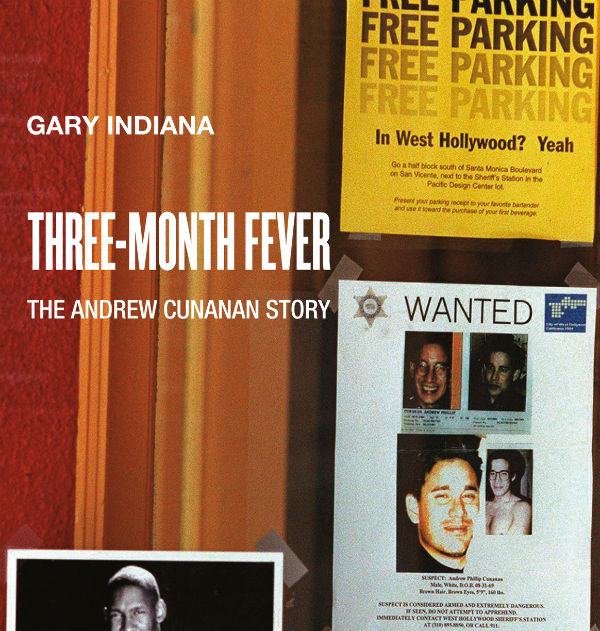

In May, Semiotext(e) republished the cult classic novel Three Month Fever, writer Gary Indiana’s riveting, pop culture-laced examination of the Andrew Cunanan murders. The reprint contains a new introduction by critic Christopher Glazek.

About the book:

First published in 1999, Gary Indiana’s Three Month Fever is the second volume of his famed crime trilogy, now being republished by Semiotext(e). (The first, Resentment, reissued in 2015, was set in a Menendez trial-era L.A.) In this brilliant and gripping hybrid of narrative and reflection, Indiana considers the way the media’s hypercoverage transformed Andrew Cunanan’s life “from the somewhat poignant and depressing but fairly ordinary thing it was into a narrative overripe with tabloid evil.”

Read an excerpt from Glazek’s introduction below.

Cunanan / Bovary

Every century has been seen its share of sodomy and mass murder, but in the twentieth century, butt-fucking and genocide reached an industrial apex, making them special objects of fascination. It’s the peculiar genius of Three Month Fever, Gary Indiana’s peerless encapsulation of the American fin-de-siecle, to gather the century’s major themes and knot them together in the figure of Andrew Cunanan, an insolvent social climber and homicidal sodomite who, in Indiana’s account, is thrillingly recast as an American everyman.

Writing from the turbulent vantage of early 2017, there’s an irresistible urge to revisit the pathologies of the late nineties—the pinnacle, in many ways, of the long Reaganite epoch now coming to an end. The murder of Gianni Versace, nuzzled between the worst years of the AIDS crisis and the rise of the Internet, prominent in a series of blockbuster deaths stretching from Nicole Brown Simpson and JonBenét Ramsey to Matthew Shepard and Princess Di, provided a febrile opportunity for journalists to workshop the era’s main theological scripts: the relentless focus on success and fame; the corresponding preoccupation with drugs and self-destruction; the siren song of easy credit; the cultural aggrandizement of travel and vacation; the urban renaissance; the triumph of liberalized marriage markets; the simultaneous worship of complexity and venality—scripts all doubly important for the gay community, which was settling into its first period of bourgeois normalcy. For Gary Indiana, Cunanan’s spree provided an opportunity to stress-test popular mythologies.

The great pleasure of reading Proust, a critic once asserted, is that he relieves you of the anxiety that you might be smarter than the author. Gary Indiana, whose writing sparkles with extravagant insight, pounding the reader with an endless succession of triple axels, affords the same pleasure: in his books, art dealers hawk work with “the mentality of pork butchers who keep both thumbs on the scale,” a reticent witness speaks to the FBI about a murder with a “serene detachment… as if an appliance he had once leased were now suspected of causing a warehouse fire.” No, you don’t write like this, whoever you are. Gary Indiana is the Eminem of American prose.

Despite his virtuosity, or perhaps because of it, Indiana has had the bad luck of being misidentified as an “experimental writer,” even though his most important work is formally conventional by the standards of the post-war avant-garde. Three Month Fever, his greatest novel, aspires to a kind of realism. Propelled by penetrating observation and telling details, the text is intermittently embellished by orthodox techniques that have been in wide use since the 19th century, like free indirect discourse and documentary collage. More accessible than experimental, the novel is also shriekingly pertinent, not only to a gay or niche or “downtown” audience—the kind that thrills to the slasher edginess of a writer like Dennis Cooper—but also to the wider “general reader” who has heard of Brett Easton Ellis, and who sustains corporate media and the mainstream elite. Saddled with an enthusiastic cult, Three Month Fever would have found its natural home in less delusional times among readers like Cunanan himself—that is, among conscientious disciples of general-interest magazines, which barely noticed the novel when it came out. On the other hand, if the world had been less delusional in 1999, Versace might never have been killed, and the book might never have been written.

“Major” American postwar fiction, the kind written by authors like John Updike and Richard Ford, and reviewed, sometimes by those same authors, in places like The New Yorker, tended to focus on suburban dads; its more recent practitioners, plying a diminished successor genre marketed as “literary fiction,” have dwelled on similar characters, though now the men are often childless and live in cities. Andrew Cunanan, parodied by journalists as a rakish SoCal psychopath, cuts a different figure. A steely cipher with moderately good looks and encyclopedic knowledge of useless worldly details, Cunanan emerges not as a postmodern reboot of Harry Angstrom but as something much larger and more portentous: an American reincarnation Emma Bovary.

Like Flaubert’s Norman housewife, Cunanan is a restless striver from the provinces (“credulous San Diego”) burdened by a writerly imagination and an unquenchable thirst to circulate in high society. Like Emma, he racks up enormous debts in his quest to project a golden aura, credit arrangements that gradually unwind in a paroxysm of mania and death. Both characters are preoccupied with fetish objects—Andrew with designer clothes and watches, Emma with bracelets and bangles—and mesmerized by the coded signals they believe such objects emit (“Andrew thought you could tell how someone voted,” Indiana writes, “by their choice of an olive or a beige refrigerator”). Like Emma, Andrew is simultaneously a fabulist and a compulsive consumer of fables, a “prosumer” sponge for media clichés and also a sensitive observer of things he cannot name, like the “pattern of flesh on a person’s hands” or the “grain of an uncooked steak.” Both Emma and Andrew stand in for their readers, their authors, and the psychic desperations of their eras.

Like Flaubert’s Norman housewife, Cunanan is a restless striver from the provinces (“credulous San Diego”) burdened by a writerly imagination and an unquenchable thirst to circulate in high society. Like Emma, he racks up enormous debts in his quest to project a golden aura, credit arrangements that gradually unwind in a paroxysm of mania and death. Both characters are preoccupied with fetish objects—Andrew with designer clothes and watches, Emma with bracelets and bangles—and mesmerized by the coded signals they believe such objects emit (“Andrew thought you could tell how someone voted,” Indiana writes, “by their choice of an olive or a beige refrigerator”). Like Emma, Andrew is simultaneously a fabulist and a compulsive consumer of fables, a “prosumer” sponge for media clichés and also a sensitive observer of things he cannot name, like the “pattern of flesh on a person’s hands” or the “grain of an uncooked steak.” Both Emma and Andrew stand in for their readers, their authors, and the psychic desperations of their eras.

As Indiana intuits, gay men, with their zeal for status-seeking and talent for false posturing, are the rightful heirs to Bovarysme. Given that the most admired heterosexual relationships in the United States are infected by austere moralism, prime-age gays are the closest thing we have to would-be courtesannes. In Three Month Fever, Andrew is not a “flaming queen,” but he does have “that hyperbolic theatricality, everything calculated to amuse or impress.” Everybody in society pretends to be richer and happier and more successful than they really are, Indiana seems to tell us, but gay men, still paradigmatic outsiders, perhaps most of all. Whether this is a consequence of years of practice at subterfuge, or, alternatively, of the intensity of intermale competition, where every rival is a potential lover, the novel doesn’t say. Three Month Fever features a gay world where solidarity has been replaced by a brutally enforced pecking order from which individual relationships are no refuge. Everyone belongs to “the community” more emphatically than they do to one another. Andrew’s paradox is that he is entirely public—“a sort of human special effect—a walking gay bar.” He exists only in the telling: the sum of his own lies, the lies told about him by acquaintances, and the fresh lies dreamed up by the press. Like Emma Bovary, he lacks true interiority.

The critic Peter Brooks once provocatively charged that Madame Bovary is “the one novel, of all novels, that deserves the label ‘realist.’” Brooks felt the novel had earned the label because Flaubert, ideologically committed to piercing popular illusions through withering description, had successfully conveyed that narrative was itself a lie and a dead end. Storytelling, in Flaubert’s famous formulation, depends utterly on the “cracked kettle” of “human speech… on which we tap crude rhythms for bears to dance to, while we long to make music that will melt the stars.” Brooks considered Flaubert an apocalyptic writer, a man so bereft of faith in the sovereignty of the imagination or the goodness of people that he wielded his pen as a world-destroyer, accumulating broken language and descriptive details as a brief against reality, which he considered irredeemably corrupted by cliche. Flaubert was put on trial for Madame Bovary’s alleged obscenity, but also for his poison-tipped promotion of “la littérature réaliste,” which Flaubert’s prosecutor called an affront to art and human decency.

Like Flaubert, Gary Indiana has a congenital urge to debunk. He practices what we might call “deflationary realism,” a craft distinct from the so-called “hysterical realism” of writers like David Foster Wallace and Zadie Smith, whose imaginations are more powerfully laced with sentimentality. Although Indiana’s novels have not led to any legal indictments, they have often led critics to accuse him of immorality or cynicism. The New York Times, for example, in reviewing Indiana’s earlier novel Resentment, a work of speculative fiction loosely based on the Menendez brothers trial, took Indiana to task for “his absurdist bleakness” and “alienating nihilism.” The novel’s “densely written pages are so relentlessly focused on the catastrophic side of human nature,” the Times wrote, “that one is driven to ask, what’s the point?” In 2015, the literary magazine n+1 complained that Indiana’s cynicism and “blasé knowingness” left no room for the “traumatic,” the “tragic,” the “romantic,” or “the revolutionary.”

Certainly Three Month Fever, like Madame Bovary, is too preoccupied with cliché to embrace the mawkishness demanded by critics. Trauma, tragedy, romance, and revolution might be themes that appeal to Bovary, but they are less relevant to Cunanan, who, instead of taking cues from novels, bathes in the secular clichés of magazine journalism. Far from a romantic, Indiana’s Cunanan is an incandescent source of “hot takes,” learning his best tricks from the fatuous storytellers of Vanity Fair. He is especially hot for “turning points.” As Indiana writes: “Andrew collected ‘turning points, recounted them gravely in heart-to-heart conversations—the real turning point for me was getting involved in AIDS prevention work, Andrew might say, or, I think Iran-Contra was a major turning point for a lot of people. In spells of fabulism it might be, The big turning point was when we left Israel.” Where Emma focuses on primping her appearance, “filing her nails with the care of a metalsmith,” Cunanan primps his backstory, embroidering his personal history with ever-more theatrical details: a wife and child left in San Francisco, a bisexual father working for Ferdinand Marcos, a career in the Navy. In letters to his ex-lover and eventual victim David Madsen, Andrew effectively publishes an epistolary issue of Vanity Fair, loading his dispatches with witty aperçus about bullfights and vomitoria and Corsican manners and Saint-Jean-Cap-Ferrat. When Cunanan closes his eyes and sinks into “reverie,” the phrases that fill his mind’s void are headlines: “Merger of Nynex and Bell Atlantic Clears U.S. Hurdle… Trial begins in the Oklahoma City Bombing Case.” Abjuring the labels “True Crime” or “Nonfiction Novel,” Indiana has declared Three Month Fever a weaponized “pastiche”—an attempt to dissolve those “unsatisfying modes” by reproducing an episode warped by journalistic nostrums and therefore “inextricable from its own hyperbole”. Holding the line against “fake news,” the novel embraces realism as an assault on the world’s unreality.

It’s tempting to believe that Indiana undertook the project of Three Month Fever as an enraged response to a very specific journalistic inaccuracy: the thoughtless canard, widely-circulated at the time of Versace’s murder, that Cunanan, who had physically ballooned in the weeks leading up to his killing spree—and whose credit card bills betray ravenous feasting at restaurants such as Denny’s—was in the throes of a crystal meth binge. “One indisputable characteristic of people on crystal meth is,” Indiana notes in pained exasperation, “is that they don’t eat.” But the average journalist, whose range of earthly experience turns out to be startlingly restricted, has no way of knowing this.

Indiana claims to have written Three Month Fever as “a propaedeutic lever with which to bury the consumer” in “indelible abjection,” And yet Indiana is plainly not oppressed by language or reality to the same dark extent as Flaubert, despite any cranky protestations. For one thing, he is palpably tickled by Americana, and especially by the stern officiousness with which names and concepts are paraded about (“the so-called Rumpus Room” in Resentment, the “trite decadeism of Joan Didion”). And while Three Month Fever might not contain enough of a moral to clear the considerable hurdle of Millennial gushiness, the novel does exalt a recognizable ethic: the ethic of “worldiliness” itself. As Indiana writes in his introduction to Three Month Fever:

I have, in my lifetime, known five murderers (that is, five that I know of), two of them documented serial killers. With one exception, I knew these people either before they killed or before their crimes were discovered—in other words, knew them as normal people in the world rather than as murderers, and although I have lived a rangier life than some, it’s my suspicion that this is not such a bizarre circumstance.

Of course, Indiana’s unusual closeness to mass murderers a very bizarre circumstance indeed. The function of his revelation is to hector the reader, as if Indiana can barely imagine how one could go through life without at least once crossing paths with a multiple murderer, or going on a meth binge, or selling one’s body for money. The complaint is justified. Why doesn’t the reader know any serial killers? What kind of lives have we been living? Not modern ones—not most of us.

Aside from looks and cold-hard cash, worldliness is the most valuable currency among homosexuals, conferring an aura of hard-boiled acuity that can substitute, if need be, for classical markers of masculinity. Just as Cunanan matter-of-factly glosses European capitals for non-initiates like David Madsen (and just as Flaubert, the son of a Norman doctor, pulled back the curtain on dreary Rouen for readers of the Revue de Paris) Indiana positions himself as a seasoned insider explaining the facts of life to the cloistered masses.

Indiana’s exaltation of worldliness and rage against naiveté has scandalized innocent reviewers, but hidden beneath his prose’s urbane exterior is a Proustian generosity. While Indiana’s literary method is to deflate the world he depicts, that world starts off considerably inflated, with ordinary people having thoughts and leading lives as complex and textured as Indiana’s own. The world that Indiana presents as fait accompli, is, in fact, a sci-fi of intelligence and erudition, a fantasy realm where sugar daddies riff on soybean futures at champagne-soaked soirees while their charges debate the aesthetic merits of To Die For. Such a scene has never occurred in recorded history—not in San Diego—but it suggests deep wells of magnanimity for Indiana to suggest that it might.

The world’s complexity is an astonishing thing to apprehend, and most people don’t apprehend it all, except to denounce it. At the moment, it looks like the populist revolt against complexity is perhaps the defining struggle of the coming new era. Gary Indiana, to an almost unique degree, is neither frightened of complexity nor seduced by it. His gift is to imagine a world where intricacy trickles down, not as a hysterical detail or an apocalyptic omen, but as a vector of empathy. Everyone’s life is complex, whether they realize it or not. Not everyone is a spree killer, but at some subterranean level everyone wants to be.

THREE-MONTH FEVER 2017. REPRINTED WITH THE PERMISSION OF THE PUBLISHER, SEMIOTEXT(E). ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.