Appreciations: Christina Hutchins’ “Vigil”

Author: Thomas March

May 24, 2016

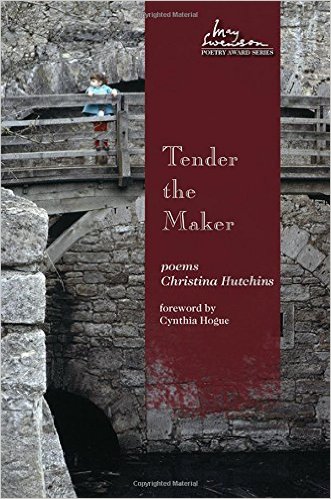

Every month, “Appreciations” looks closely at a poem or poems from recently-published books by LGBTQ poets. Each column celebrates new work by appreciating some of the figurative and formal achievements of these poems. This month’s poem is Christina Hutchins’ “Vigil,” from her recent collection Tender the Maker (Utah State University Press, 2015):

Vigil

We watched as a man came

______and took away the body

______to be burned.Shut for all

the days of my

father’s dyingin death

his left lid

would not stay closedbut opened alone

Wider than life

the blue eyegazed unflinching

directly at my mother

and me and my brotherwho groaned

a sob and turned

his face intomy chest where

I shielded him

not at all

The epigraph of Christina Hutchins’ “Vigil” identifies the transitional circumstances of the poem, in which a deathbed vigil yields to a vigil of witness. The epigraph’s neutral tone and anonymity—of the deceased, the remover, the speaker, and the other viewers—capture the astonishment of loss and gesture toward the universality of grief. In the more intimate moments of the poem itself, an extended synecdoche, the defiantly open eye of the departed father, signifies both his absence and his transformed presence. The poem’s concise tercets and Hutchins’ deft enjambment consistently create a sense of emphatic deliberateness, as the momentousness of this new absence expands moment by moment, observation by observation. Each new phrase completes or complicates what comes before, recreating the slow dawning of new truth that is so common to the first stunned moments of grief, in a room that is suddenly free of dying but full of absence.

From its first word, the poem asserts a finality that the remainder of the poem will investigate and transform. The terse participle “shut” suggests completion, in advance of lines that less abruptly describe the extent of the process of dying itself. The first three lines comprise a participial phrase modifying the sentence’s deferred subject, “his left lid.” This opening phrase subtly emphasizes the duration of the deathbed vigil, a time described as “father’s dying,” with the gerund “dying” indicating an ongoing process rather than, as “death” might suggest, an event. Identifying the duration only vaguely as “all/the days” can imply, in its imprecision, the exhaustion or even the impatient exasperation that can accompany vigilance. The second tercet begins with the phrase “in death,” which first seems to modify “dying,” reflexively emphasizing the fact of the death itself. By the next line, though, the phrase modifies “his left lid,” which, as it turns out “would not stay closed.” In its dual function, the phrase “in death” stands at the junction of two very different stillnesses—waiting for death, and waiting for the removal of the body. It also marks the dying as the beginning of something new.

The dramatic irony of the eyelid that “would not stay closed” in death inaugurates a symbolic defiance in and of the vacant body that the life it once contained could no longer muster. The transition to the third tercet elaborates on the uncanny persistence of the eyelid, which has now “opened alone.” The poem’s lack of punctuation becomes especially significant now. The first sentence of the poem could end grammatically with the word “alone.” But with only the capital “W” to indicate the beginning of a new main clause, the participial phrase “Wider than life” can modify both the verb phrase “opened alone” and the new subject, “the blue eye.” Symbolically mimicking the opening of an eye, the poem transitions here from a sentence whose subject is the “lid” to one whose subject is “the blue eye” itself, as the mention of the iris’ color echoes its liveliness. It is this lingering vividness that the next line reinforces, indicating that the eye “gazed unflinchingly”—empty, perhaps, but still powerful. “Unflinching” usually suggests determination, forcefulness, stalwart reliability—a word that is all the more powerful in its ironic distance from this new, unfamiliar cause of its unwavering intensity.

It is only now, as the objects of this “gaze,” that the speaker identifies the other mourners, their connection to the deceased, and their collective sense of powerlessness. Fixed by the directness of the eye—somehow staring “directly” at each of them simultaneously—their reactions appear in a series of subordinate clauses that redirect attention to the mourners just as the “the blue eye” and its attention remain the subject of the sentence itself. Treating “groaned” as a transitive verb and enjambing the first two lines of the fifth tercet—“who groaned/a sob”—allows for a nuanced expression of the brother’s grief, one that lingers meaningfully, if momentarily, in his initial agony before identifying the expression it produces.

The release of the tensions of vigilance allows the brother’s eruption of grief, but the poem ends with neither grief nor the comfort it seeks. In seeking comfort or solace by “turn[ing] his face into//[the speaker’s] chest,” the brother is also breaking contact with the father’s lingering gaze. The unclosed and unclosing eye of the father gestures forward indefinitely, in symbolic vigil of its own, as the ever-watchful presence of the parent-as-figure—whether from some imagined afterlife, or from within the minds of the living. No matter our age, we are always our parents’ children. Their deaths are always the deaths of our first all-knowing, all-seeing gods.

The final two lines of the poem cleverly embody the ambivalence of the speaker’s response: “I shielded him/ not at all.” The idea that the speaker has “shielded” the brother forms only to be contradicted by the poem’s final, obliterating line. It could be that the shock of speaker’s own grief has made it impossible to provide solace. But the choice of the verb “shielded” is an especially productive one. It allows for the possibility that comfort may have been offered and received, after all—comforting is not the same as shielding. Comforting prevents nothing. It protects from nothing. By invoking the power to protect only to deny it as the poem ends, the speaker confronts a fundamental sense of impotence in the face of death. And the final line and phrase of the poem, “not at all,” reinforces the very absence and emptiness that the poem explores.

In the collection’s endnotes, Hutchins reveals that “Vigil” is “in conversation with” Emily Dickinson’s “Sleep is supposed to be.” The conversation is an ironic, even darkly playful, one from the start. The final “sleep” here is not, as it is in Dickinson’s poem, “the shutting of an eye” at all. Dickinson’s poem ends with waking, in a turn toward metaphors of resurrection and eternity. Hutchins’ poem ends with the heavy ambivalence of grieving, in an emptied room that is full of afterward:

Sleep is supposed to be

Sleep is supposed to be

By souls of sanity

The shutting of the eye.Sleep is the station grand

Down wh’, on either hand

The hosts of witness stand!

Morn is supposed to be

By people of degree

The breaking of the Day.Morning has not occurred!

That shall aurora be–

East of eternity–

One with the banner gay–

One in the red array–

That is the break of Day!