Dirk Vanden: Pioneer Of Gay Literature

Author: Drewey Wayne Gunn

August 10, 2011

“There are those who believe that Gay Liberation started at the Stonewall Inn in Greenwich Village on June 28, 1969. That is like believing that a flower can blossom without having been planted…”

Before a series of landmark decisions by the U.S. Supreme Court concerning obscenity, beginning in 1957 and accelerating and changing direction throughout the 1960s, American book publishers worked under a common set of truisms, some based on fact and some simply assumed. Fact: Anything deemed obscene was prohibited from being sent through the U.S. postal service. Fact: Homosexuals, by their very nature, were considered obscene; therefore, any book with a homosexual as a main character could be considered obscene, banned from the mails, and any publisher violating that ban could be prosecuted.

Assumption based on some empirical evidence: Some ways around the ban were to show the intrinsic immorality of homosexuals by having them commit other crimes (Vidal’s The City and the Pillar); to have them repent of their base ways and either commit suicide (Blair’s Strange Brother) or convert to heterosexuality (de Forrest’s The Gay Year); or to have a manly straight guy take care of the menace by beating the homosexual up (Jackson’s The Fall of Valor) or wiping him out (Spillane’s Vengeance Is Mine).

Assumption based on no evidence whatsoever: Although straight men liked to read novels about lesbians, there was no lesbian or gay male audience large enough to support works of fiction aimed at such a narrow readership. Therefore, any novels with a significant gay content had to be aimed at a mixed audience of straights and gays.

Fact: Smut sells.

As the obscenity laws were loosened up and redefined, publishers — primarily of paperback originals — began moving hesitantly into the newly opened market. Dr. H. Lynn Womack’s Guild Press in Washington, DC, was the first gay press to have an all-gay catalog, but it suffered constant legal and financial woes despite having been the cause of a 1962 landmark Supreme Court decision and finally went bankrupt in 1974. Most of the publishers were on the West Coast and specialized in straight erotica. They were exclusively interested in economic gain and only remotely in patronage of gay writers. These presses began their first forays into the field in 1964-65. Their finding the gay novels sold well, the number of books published exploded in 1966, with Greenleaf Classics in San Diego quickly dominating the scene. Its 1966 novel Song of the Loon by Richard Amory was the first “gay best-seller.” By 1969, the year of the Stonewall Inn revolution, some six hundred gay pulp novels had joined their lesbian sisters.

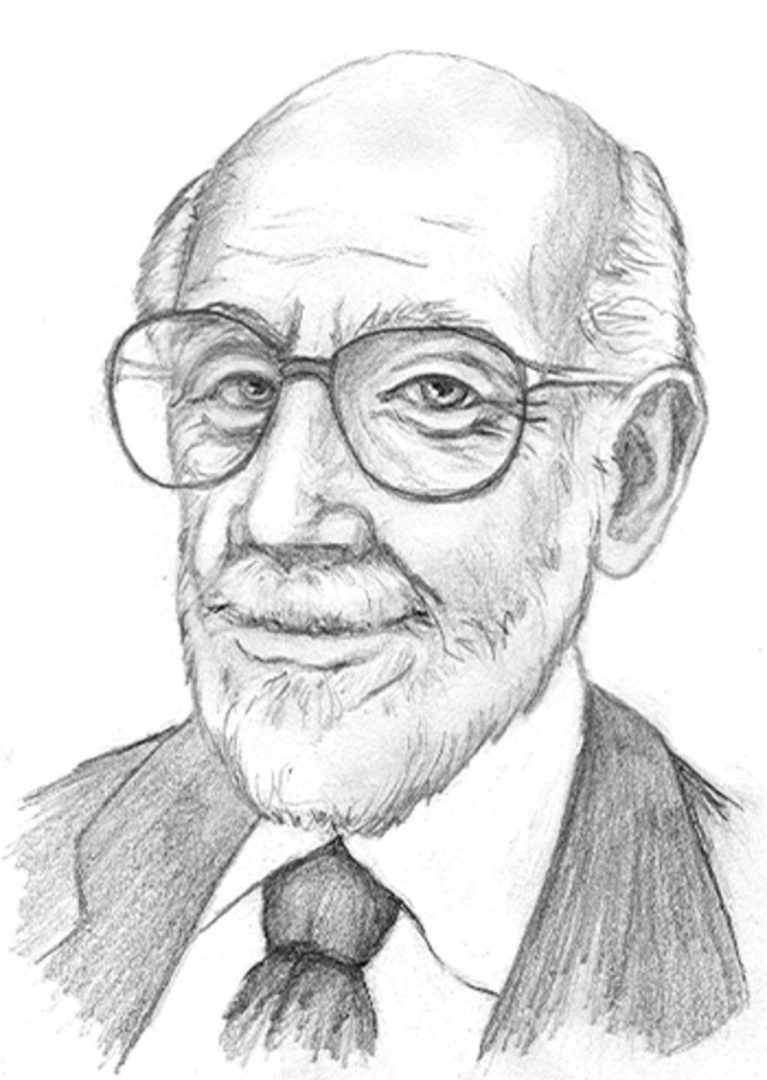

Richard Fullmer is one of that unfairly forgotten and largely misunderstood wave of pioneers who share the singular distinction of being the first significant group of gay authors to write for an almost exclusively gay readership. Using the pen name Dirk Vanden, between 1969 and 1971 he published seven novels with Greenleaf, Frenchy’s Gay Line, and Olympia Press. He is one of the few survivors from that rich period, most of his peers now lost to AIDS and old age. What he has to say is absolutely invaluable to establishing a full history of queer literature. The following interview took place via email the week of July 11, 2011.

DWG: Describe for readers who came of age after Stonewall what the literary scene was like when you came of age.

DV: I had my first overt homosexual experience at age seventeen, in 1950, during my last year of high school in the provincial town of Vernal, Utah. It was the most traumatic experience of my life, and it changed my life almost completely. It produced a crisis of faith which forced me to choose between religion and reality. Up to that point I had been the best-little-Mormon-boy-in-the-whole-wide-world, my faith unchallenged and unquestioned, but when I asked my bishop about meeting “a man who likes other men,” I was told, “Run from that man as you would run from a snake. He is an abomination in the sight of God!” I was forced to test my faith in God, and it failed miserably. But I couldn’t stop being Queer.

I had no one to talk to, no siblings or close friends, and nothing to read that would explain those mysterious and frightening feelings I was having. In 1950 the country had just been through World War II and was involved in Korea. Macho soldiers were the role models for young boys. Any references in the media to perverts or deviates were oblique and thoroughly negative. Starting college in Salt Lake City, I discovered a bookstore where I did find an unmarked Gay section: Michael de Forrest’s The Gay Year, Charles Jackson’s The Fall of Valor, Nial Kent’s The Divided Path, James Barr’s Quatrefoil, Fritz Peters’s Finistere, Truman Capote’s Other Voices, Other Rooms, Gore Vidal’s The City and the Pillar. Radclyffe Hall’s The Well of Loneliness was an enormous tome about the heartbreak of Lesbianism. All of the literature available – that I knew about – was negative and suicide-inspiring.

I had decided to go into theater as a profession, as an actor or director, so I knew about plays that were about homosexuality. Lillian Hellman’s The Children’s Hour and Robert Anderson’s Tea and Sympathy were both anti-Gay. Anderson’s propaganda preached that a sad, misguided young man can be cured of his homosexuality overnight by seduction by an older woman. Hellman’s story told how two women’s lives could be ruined by childish gossip that they were Lesbians – which happened to be true. All other theatrical references that I knew about were negative. Homosexuality was classified as a mental illness, a psychological dysfunction, a Freudian neurosis, and a criminal offence worldwide.

I once spent eighteen days without being charged, in the Mobile Alabama City Jail, because I had been in the company of a suspected homosexual who was arrested for passing bad checks. In popular consciousness, it was considered reason enough for murder, and any “real” man would be considered justified in killing a queer who propositioned him.

I wrote my books primarily for myself, to help me explore and understand myself. But I also wanted to share my experiences and insights with others like myself. One thing I found early on, and it has confounded me ever since, is “internalized homophobia.” It was worse then, but too many of us still tend to hate ourselves for being what we are. I wanted to mitigate that self-hatred. One of my reviewers called me “sage but incorrigibly idealistic.” I still plead guilty to that incorrigibility.

DWG: As you know, both The Golden Age of Gay Fiction, which I edited in 2009, and the collection 1960s Gay Pulps: The Misplaced Heritage, which Professor Jaime Harker and I are now co-editing, argue that one must not overlook the nearly six hundred gay pulp novels that were published by 1969 if one wants to understand the full scope of gay fiction in America. Though I came of age then, I’m still piecing together what you writers were trying to achieve in your novels. Tell me about it from your perspective. And explain to me a little why Richard Amory had such an impact on you.

DV: I started my first novel during my first year of college, 1951. To Themselves Unknown explored the life of a young Mormon boy in college discovering his homosexuality and questioning his religious faith. I wanted to tell “the truth” about homosexuality, what I had personally discovered: that it wasn’t evil and nasty and a mandate for suicide. Also, I wanted very much to expose Mormonism as a fraud; the closer I looked, the crazier it seemed. I had been amazed, as I started meeting other Gays and Lesbians, to discover that they were all nice, decent people, with respectable jobs, and not depraved, evil sociopaths determined to seduce everyone’s children and destroy the world. Sometimes, surprisingly, they seemed in fact better people than the “Good Mormons” I knew before leaving the church. The novel was more a philosophical and psychological examination than sexual. The only sex in the book was implied. I didn’t even wonder who might publish it, I wrote it simply because I felt compelled to write it. It was My Story.

I worked on To Themselves Unknown during the seven years it took me to graduate from the University of Utah with a BFA in Theater Arts in the summer of 1958. I entered the novel in a contest for a summer writer’s workshop at the university conducted by the then-famous novelist Albert Guerrard. To my surprise, I was given a tuition-scholarship to the workshop, and my novel was given to Mr. Guerrard for criticism. Nothing was said about my book until the last day of classes, when he spent ten minutes reading aloud one of the chapters – where the hero goes to his old home and tries to reconnect with his father, fails, and goes back where he had been. The class applauded when he finished. Mr. Guerrard told them: “That was from one of the best first novels I’ve ever read. Unfortunately, it’s about homosexuality and has almost no chance of ever getting published.”

In Hollywood, a year later, I worked with a writer who wrote screenplays, and he had me send TTU to his agent in New York, Martha Winston, with Curtis Brown, a well-known, respected agency at the time. She tried her best for a year to sell it for me, but couldn’t find a publisher.

As a result of publishing two short stories in ONE Magazine, I learned about Guild Press in Washington, DC, and early in 1966 I sent TTU to Lynn Womack (“I’m not a martyr. But if homosexuals want a literature, they have a right to it”). He very quickly bought it for $250 and promised that the book would be a best-seller and establish me as a major author whose subject happened to be homosexuality. Before he could do anything, vandals broke into the warehouse where Guild Press’ entire inventory was stored, along with my manuscript and others; everything was trashed and then burned. Guild Press was out of business, and all that was left of my book was a yellow onion-skin carbon copy in my files. Dr. Womack told me I should keep trying to find a publisher for TTU, that it was an important statement that needed to be published.

Shortly thereafter, on a Sunday afternoon in the summer of 1966, I went to the beer-bust at The Falcon’s Lair, one of Hollywood’s early Levi’s/Leather bars. The bartender knew me and put a book on the counter when he brought my beer, saying: “You have got to read this book! It’ll blow your fuckin’ mind!” Indeed it did. It was Richard Amory’s Song of the Loon. I had no idea about the literary form it was based on, a traditional Spanish romance, but it was the very first book I had ever read which celebrated homosexuality! Instead of Cowboys and Indians shooting and killing each other, his jubilant book is about Fur-Trappers and Indians fucking and sucking and loving each other, without a female in sight! They sing love songs to each other and recite love-poetry. The hero is taught to love himself, and other men in the process. And even though the book ends before “happily ever after,” that is clearly hinted.

With no idea of formalities involved, I retyped To Themselves Unknown and sent it to Greenleaf Classics, which had published Song of the Loon. The manuscript came back a few weeks later, along with four paperback novels and a letter from an editor thanking me for submitting TTU, which had a “literary quality” but was “not suitable” for Greanleaf’s Pleasure Reader line because of the lack of graphic sex in the narrative. He suggested rewriting the book with “hot sex on the first page,” then grafted into the story as often as possible. In the returned manuscript there were several places where someone had written in the margins in red ink: “Good spot for fag-hots.” As an example of what they were looking for, he sent The Story of O and Emmanuelle, both published by Olympia Press in New York. And he included two Gay novels. One was a Gay spoof of Mickey Spillane. I think the other was entitled Homo, Sweet Homo. They were awful, and I couldn’t finish either. I was certain that both had been written by someone straight pretending to be Gay, totally condescending and misinforming.

I was infuriated and insulted and challenged. Just the idea that my good novel could be turned down because it didn’t include graphic sex was infuriating. It was better without sex than any of the four books he’d sent as examples of what he wanted, but it wasn’t “stimulating.” Still, he had invited me to send my next book to him if I would follow his prescription: “hot sex on the first page and as often thereafter as the story permits.” I wrote Tom, Tom, the Piper’s Son trying to follow his formula, but without the flagrant homo-sex of those two he had sent me. I tried to be more poetic, more like Richard Amory. Greenleaf bought it for $800, all rights, no royalties. They invited me to write another, but to, please, use more graphic sex! It was Porn I was writing, not Great Literature!

My problem was, I couldn’t write smut. It had to be at least well-written – what has now become Gay Erotica. I told the stories of real men examining an unexpected sexual aspect of themselves, but nobody killed themselves; they all ended happily with the lovers moving in together in spite of the world. I planned to use the published Tom as a means of finding another publisher for TTU, one that would let me write about homosexuality without the emphasis on sex.

In the process, I realized that writing about sex was liberating and exciting. And fun. Like homosexuality, it was an escape from the constrictions placed on living by the conservative Christians who ran the country. I could use all those forbidden words to arouse my readers, as I was being aroused by writing them. I decided to use Dirk Vanden as my pseudonym for the “fag-hots,” and to keep Richard Fullmer for the more legitimate stuff.

In the next six months I wrote three books especially for Greenleaf, all of them very deliberately as “hot” and perverse as I could make them and still tell a believable Story. Tom, Tom, the Piper’s Son was about a married father discovering his homosexuality. Hatters and Hares examined Gay masochism; The Stag in the Tree looked at Gay sadism. Exile in Paradise was my fantasy answer to Amory’s Song of the Loon.

On January 15, 1969, Greenleaf sent me three copies of my first published Novel: Who Killed Queen Tom? The cover showed a man with a knife in his heart, though the novel was not in any way a murder mystery, but a coming-out story. The book had been printed upside-down and backward. The cover was actually on the last page of the book and was upside-down to the rest of the book, which started on what should have been the last page. It was the publisher’s seemingly homophobic inside joke: Going in the Back Way. Someone had gone through my novel and had added such phrases as “pulsating purple cockheads spurting volleys of creamy ambrosia!” to my poetic-sex, ruining it and the book as far as I was concerned. The typos were atrocious. It was nothing I could ever proudly show anyone. And now my name would be forever connected to a piece of badly-written “fag-hots.”

February 1, six more freebies arrived: The Leather Queens and Leather. There were not that many changes to Hatters and Hares and The Stag in the Tree, except to the titles. The Leather Queens was taken from a derogatory remark made by one of the minor characters: “They’re just a bunch of fucking leather-queens!” That put-down became the title of the book, which was not even about Leather except incidentally.

Twin Orbs (Greenleaf First Edition Cover)

My final book from Greenleaf arrived around Valentine’s Day: Exile in Paradise had become Twin Orbs. The new title came from a description of the narrator’s lover’s testicles on the first page. The cover was a woodcut of a naked man with spheres depicting identical planets superimposed on the cheeks of his ass. It did make you wonder what the hell it might be about. All four covers were nearly identical: red borders and phony woodcut figures of men in pain. My dismay was exceeded only when I went into Le Salon on Polk Street in San Francisco shortly afterwards and saw an entire wall filled with red-and-white books almost identical to mine, all with phony woodcuts and fag-hot titles. Mine were lost amongst the chaos.

DWG: But that was not the end of your writing career.

DV: When I moved to San Francisco in 1969 to live with my new lover, Herb Finger, I had decided to stop writing altogether. It had been endlessly frustrating, and the results were overwhelmingly disappointing. It seemed that nobody I knew had heard of my books or Dirk Vanden. There was a prejudice against “Gay dirty books.” Even the men who read and enjoyed them tended to treat the author as being less than a “real” author: “How can you be proud of writing dirty books?”

There was no way I could determine if my books were selling or not except by going into Le Salon, San Francisco’s premier dirty-book store, and asking the owner, “The Dirty Old Frenchman” (as he called himself), how they were selling. After a few visits, he told me of his plans to start a publishing company of his own, calling it Frenchy’s Gay Line, and asked if I was interested in writing his first book. He offered $500 and wanted something ASAP. I wrote I Want it All for him in two months, from April 22 to June 20. I based it on one of Herb’s favorite bath-house-sling acid fantasies: being gang-raped by cowboys.

About that time, I started finding very positive reviews of my books in the Gay bar newspapers and “underground” magazines, and I soon made the acquaintance of the owner/publisher/editor/head-writer of California Scene, who gave I Want it All a very good review and asked if I’d let him publish an interview in his magazine. I was thoroughly flattered and agreed, and the next Sunday, at the Speak-Easy bar, he tape-recorded an interview, which he published the next month. It detailed all of the problems I’d had with both Greenleaf and Frenchy’s.

I Want It All (Frenchy First Edition Cover)

A friend of Herb’s was on the board of SIR – The Society for Individual Rights, SF’s premier Gay Rights organization, which published a monthly magazine called Vector. He forwarded a letter to me from Richard Amory, who had read the interview in California Scene and wanted to get together and compare notes. He had an idea for Gay authors to start an all-Gay publishing company. He directed my attention to an article by him in the latest Vector called “The Real Name of the Game Is Screw You, Queer Boy!” He talked about having the same problems I had experienced with Greenleaf, the feeling that we were only just barely above contempt – just enough to use our talents to make money for them.

We got together for dinner several times and felt a mutual rapport. I was very excited about the prospect of working with him, and I wrote an “answer” to his article for Vector, calling it “The Time Has Come the Walrus Said…,” which ended with an invitation to anyone interested to a meeting at SIR to discuss the formation of an all-Gay publishing company to be tentatively called The Renaissance Group. Richard invited Larry Townsend from LA, Phil Andros (Sam Steward), Peter Tuesday Hughes, and Douglas Dean to take part in a discussion panel. None of us knew each other before then, but I was really looking forward to working with all those authors to start something new and audacious: an all-Gay company publishing all-Gay material for all-Gay readers.

We never did find anyone interested in financing our dream. Richard and I recorded a discussion about the meeting on June 15, 1970, and the frustrating non-results, calling it “Coming Together: The Beginning of What?” It was published in Gay, the monthly news magazine in NYC. Very shortly thereafter, each of us who had been part of the panel received an invitation from Frances Green, newly appointed editor for Olympia Press’s Gay Line: The Other Traveller. She invited us to send our next manuscripts to her for publication and distribution in the USA – and UK as well! I sent them All Is Well, and they sent me a contract for royalties after a certain break-even point. It looked as though our dream had come true, just not quite as we planned it. Richard sent them Willow Song. Larry sent The Sexual Adventures of Sherlock Holmes. I’m not sure what the others sent. Before any of us could collect any royalties, Olympia declared bankruptcy and stopped publishing anything.

We had burned our bridges and had no place to go. Townsend started his own publishing company in order to continue writing. Greenleaf had gone belly-up as well (its editor was in prison for having published The Illustrated Presidential Report on Pornography). Richard and I had no real resources. He was living on a teacher’s salary; I was depending on sales of my paintings and drawings, illustrating articles and annual report covers for American Express and Fireman’s Fund.

DWG: Other pulp writers, not just Townsend, continued to write to the end – Joseph Hansen and Samuel Steward – and William Maltese has never stopped. So there must be more to it than just having burned your bridges.

DV: Richard and I were both sick and tired of fighting with publishers, of being treated as though we and our books were trash and didn’t matter. The fight was too brutal and the rewards were actually painful. Herb and I took Richard to see the Grand Opening of the movie Song of the Loon in San Francisco. He had sold the book outright to Greenleaf, who sold the film rights without consulting him, giving him no further payment for anything. He’d had no input in the movie and had no idea what to expect. The movie was awful. It was badly acted soft porn: an excuse to show naked bodies. They only kept Richard’s plot-line to get from one simulated sex scene to the next, and even killed off the hero’s lover in the end. Richard was livid. He stood up in the theater as the credits rolled and yelled, “That was shit!” and stormed out. Herb and I started after him. The theater manager came running to find out what was going on. I said, “That was Richard Amory.” He said, “Who?”

Richard stopped writing when he had to take care of his lover, Matt, while he died of AIDS. Richard died shortly thereafter, in 1981, not of AIDS, but of liver failure from years of drinking. His son described him as “bitter and disillusioned” in the end.

DWG: I’m grateful that a number of pulp writers — you, Victor Banis, Jan Ewing, Roland Graeme, Vincent Lardo — have recently returned to writing fiction and memoirs. What brought you to write your unpublished memoir Pissing in the Ocean and your published murder mystery, All of Me?

DV: Bluntly speaking, I feel I deserve a little more credit than I’ve been given for my contributions to what we now consider Gay Life. My books helped define it, forty years ago, but nobody knows that. In The Gay and Lesbian Literary Heritage, Robert Nashak states that my All trilogy “helped pave the way for an entire industry of leatherman fiction and erotica.” Yet though I’m still alive, my name is dead. To most current Gay readers, Dirk Vanden is just an entry in a bibliography, classified under “pornography, homosexual.” Most of my fans died in the AIDS holocaust. Very few people alive know my books, but I think they would enjoy reading them, and I need the income! Besides which, there is more to my story than just dirty books!

After Herb died of AIDS in 1987, I decided, for no good reason, that my own end was coming soon and I needed to get ready. I realized that no one was ever going to write my story and tell my teeny-weeny part in Gay history, so if I wanted anyone to remember Dirk Vanden, I’d have to do it myself. I wrote my autobiography and called it Pissing in the Ocean, because that’s what my life seemed to have amounted to: pissing into fish piss – what’s the point? I sent a copy of it to Edmund Miller, who had done one of the pieces mentioning me in The Gay and Lesbian Literary Heritage, asking his opinion on its publishability. He replied that he found my life-story fascinating, but that it wasn’t quite ready for publishing. He never said why. He suggested instead using some of the high points of my own life in a fictionalized biography, a mystery perhaps.

It was a challenge that took over ten years to complete, and I had terrible problems finding a publisher, so I finally self-published it last year through Rosedog as All of Me (Can You Take All of Me?): A Gay Mystery. Just before Xmas last year, Rosedog put up a badly-formatted version on Kindle, which resulted in a scathing, 3-star review. As a result, the publisher and I split ways and the very few printed editions of All of Me instantly became “collector’s items.” I hope to find a new publisher soon.

DWG: And now you are reprinting some of your earlier books. I’ve seen Down the Rabbit Hole, and I hear the All trilogy is coming out in a new form. Please tell us about this project.

DV: I recently discovered that I have a new, completely unexpected kind of fan: professional, heterosexual women who read my books on their iPhones. I’ve been corresponding with a straight, professional, married woman in Australia who writes Gay mysteries as A.B. Gayle. She suggested loveyoudivine as a possible re-publisher for my classics and made that suggestion to the CEO at lyd, who thought it was a great idea and invited me to become the cornerstone of their new genre – what I call Retro-Queer: Classic Gay Erotica. Down the Rabbit Hole is the restored, original manuscript of Leather. I originally called it Hatters and Hares, but Rabbit Hole seemed a more appropriate title.

loveyoudivine has already produced each of the three separate All books as e-books, now becoming available on Amazon as Kindle and other e-book formats, every other week. In September they will publish an e-book and a print version of the All trilogy in one volume, All Together, which will feature a special free bonus: a “mental movie” of I Want it All – the next step in the evolution of my best-known story. It’s “Gay 1969 on DVD.” Depending on sales, they may or may not do the other Greenleaf novels.

DWG: What would you hope will be said about you and other gay pulp writers when a history of queer literature is written in twenty years’ time?

DV: One of my sayings in The Gospel According to Dirk Vanden (unpublished) is: “There are those who believe that Gay Liberation started at the Stonewall Inn in Greenwich Village on June 28, 1969. That is like believing that a flower can blossom without having been planted.” Most of Richard’s and my books were published before Stonewall. I would like to think that all those Gay dirty books were the fertilizer to make the Gay flowers grow. Stonewall was the first blossom of many. I would like to believe that I had a hand in defining the national Gay Spirit of which Stonewall was only the first manifestation.

In All Is Well (1971), my Author’s Note says: “There is a tremendously exciting reformation going on all over the world, and I feel that gay people are going to wake up and find themselves in the vanguard of that reformation. But in order to ‘wake up,’ we must first understand ourselves – and that, more than anything else, is what All Is Well is all about.”

I am now convinced more than ever of that prophesy’s validity. I would like to be remembered as one of the first authors to say, “It’s okay to be Gay!” I wasn’t the first. Sam Steward would probably qualify with his Phil Andros stories. Then Richard Amory. Then a whole bunch of us, including me and Larry Townsend and Douglas Dean and Peter Tuesday Hughes and, you say, six hundred other “fag-hots” authors.

I think of 1969 as The Gay Year. In retrospect I see it as a gargantuan “cumming out” party — six hundred novels saying “Cum! Cum! Cum!” Erupting all over everybody! Yes, it was definitely the Seminal Gay Year, in which the New Gay Spirit was born. I’d like to be remembered as a contributor to that birth.