Kelly Cogswell: My Life as a Lesbian Avenger

Author: Sarah Burghauser

May 10, 2014

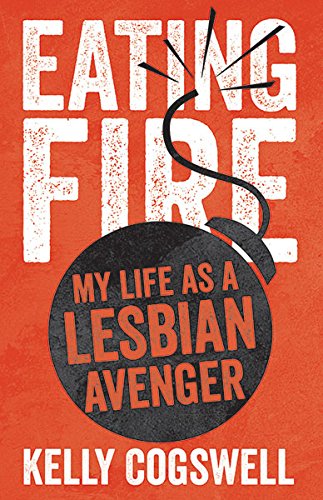

Kelly Cogswell, radical journalist and founding member of the notorious and groundbreaking grassroots activist group The Lesbian Avengers, writes about the collective’s rise and ruin and her in her vital new memoir, Eating Fire: My Life as a Lesbian Avenger.

In an email exchange, Cogswell discussed the strengths and drawbacks of Internet activism, her past work with the Lesbian Avengers, and her comprehensive Lesbian Avengers archiving project.

In your book you talk about how the Internet was, at first, a powerful organizing and connecting tool, and then subsequently you came to experience its drawbacks as well. Has your perspective on using the Internet as an organizing tool evolved in recent years?

Yes, the Internet was a revelation. After years of trying to get mainstream media to cover LGBT issues, especially dyke stuff, it was incredible to be able to bypass the gatekeepers and share ideas and information directly–and globally. Social media was even faster, and at first people thought of it as a magic bullet. Even before the Arab Spring it was hailed for its contribution to flash organizing, like with the huge demos that happened in California when Prop H8 reversed same-sex marriage there. It took a while to understand that social media was really just a form of media and communication. Twitter is a faster version of a phone tree. YouTube and Tumblr are just the latest do-it-yourself versions of posters and handbills. Ways to get the message out.

This is actually getting harder again, because the Internet is so swamped that the individual is nearly back to square one trying to figure out how to stand out and get heard.

Another downside is that the Internet can create the illusion of activism. You click on a petition and feel like you’ve done something. And they do have some effect. But virtual action is not a substitute for actually going out on the street and entering the public, physical space. The first reporting of the Arab Spring called it a revolution by Internet, but you have to remember the people in Tunisia and Egypt actually left their computers and went out into the streets. Not by the dozens, but by the tens and hundreds of thousands. And they weren’t all wired either. Most still relied on traditional media which picked up on the activity online, and spread the news.

Maybe the Internet’s biggest problem is its vulnerability. It is dependent on electricity and phone service/cell towers (how many people freaked out in New York during post-Sandy flooding?!). Angry governments have been known just to flip the switch and essentially turn it off. There was also a big fight early on about who was doing journalism and who wasn’t. “Citizen bloggers” would get cold feet and decide to just delete a post, self-censor and not take responsibility, but now it’s pretty accepted that you can’t do that if you want to be taken seriously. Protesters in Ukraine [were initially] tracked by their mobile phones, even receiving threatening tweets from the government warning them that they were engaged in illegal activities.

Is it possible to create movements that are both community-specific and also diverse/inclusive?

I’m not sure it’s possible to have perfectly egalitarian groups, but we have to act as if it were. The main thing is to pay attention, and work towards it in a systematic way, not relying on good intentions. Because we can’t help reflecting the societies we emerge from.

Reading your book, I noticed that the tensions around race, citizenship, and class the Avengers experienced echo today’s online interactions amongst social-justice savvy folks.I find much of the current mode of conversation around these difficult and vital topics to be frustrating in part because many contributions seem to be inhospitable and to lack the presumption of goodwill necessary to moving ideas and actions forward. I’ve noticed the tendency to contribute to these discussions quickly (at the speed of Internet) rather than thoughtfully. One example of this was the reaction to Ani Difranco’s letter regarding teaching a workshop at an old plantation. For me what was most disheartening about that debate was not that the beloved singer hadn’t thought through teaching a workshop on the site of so much historical violence–even if she had the intention of using it as an opportunity for healing–but that the reaction from many fans was, “You used to be so great, Ani. Now I’m never listening to your music again. You are a disappointment.”

All this to ask whether or not you see echoes of the problems the Avengers tried to work through emerging in today’s social justice efforts?

Usually I think talking is good, but it’s really only useful if it’s thoughtful, and if the goal is to develop strategies, not just point fingers and parse intentions. Sometimes it’s hard to tell if a person is a true homophobe, or just stating something awkwardly, or is a garden-variety asshole. In general I think that conversations about famous people are a waste of time. We should be talking about things within our control. Like that church on the corner sending young queer kids to get re-educated. Or the fourth grade teacher at the local school bullying little boys that like to wear pink. Those are the people in our sphere of influence. Quit blabbing and do something. Anything.

In your book you describe such big, deep group tensions. Have you had much reaction from other original Avengers? Were there particular people you ran the manuscript by before its printing or publication?

I let people know I was doing it, but didn’t show it around much. It would have been paralyzing. The upside was that it encouraged me to be as accurate as possible, put things into context, and give people the benefit of the doubt with the hope that they’d return the favor. Street activism and direct action can be really empowering, but it’s also really hard work done under enormous pressure. It brings out the best, but also the worst in people. I was no exception, so you sometimes see me behaving badly, too. Which is a little embarrassing.

In the early 90s when the Avengers were most active, the goal was to take the message to the streets, out in the open air. Where do you think the front lines of activism are located today?

As long as we’re still attacked in flesh and blood, I think we have to stay on the streets, staking a claim to physical space. Protecting our bodies, those things we live in, is the most fundamental of rights as humans: life and death, physical security versus torture, freedom versus jail. That means our most fundamental tools as citizens are mass assembly. Free speech. Rights that we can only protect with our bodies.

In terms of subject matter, we’re making a lot of progress in the U.S. on legal fronts, like same-sex marriage, but we have to find some way to deal with problems that can’t be addressed by legislation. Like homophobia inside the family and all the queer kids that get tossed out on the street. We have to grapple with violence and cultural invisibility.

The last third of your book, I thought, was so sad. You showed your own disillusionment. For me as a reader, what served as a kind of balm to those feelings of loss was your return to Kentucky. It left me with the feeling that hope can be found anywhere, even in the places we once needed to escape. As queers, we often have troubled relationships with the idea of home. Many LGBTQ artists and activists have channeled the distress of home into projects and movements. But at the end of the book you seem to have come to a peaceful place–even if it was just in that moment.

Yes, some of the book is a little sad. As an activist, you go through brief periods of seeing rapid change, then other long periods where you see things not only stagnate, but maybe getting reversed and it can drive you nuts and make you wonder if all those years were wasted. You just have to keep telling yourself that if you didn’t do anything, nothing at all would have changed. And maybe things would have gotten worse. Maybe also, there’s change going on that you can’t see. Like when I went back to Kentucky and found it more welcoming than when I left.

Likewise, throughout your book, you return to the question of citizenry. Can you talk a little bit about how your desire for and experience of home (of any kind) has informed your work with the Avengers, or otherwise?

Maybe because I left Kentucky, and my girlfriend had an even more horrible rupture with Cuba, I’m preoccupied with ideas of exile and citizenship, and those two very American and abstract wars, the Culture War, and the War on Terror. What was the impact of Pat Buchanan’s 1992 speech announcing a Culture War for the soul of America, and defining the enemies as environmentalists, and feminists, and African Americans, and setting everybody against queers? What happened when the War on Terror was launched and the enemy wasn’t just the 9/11 bombers but dissent and diversity in all its forms? I started to feel even more like a foreigner in my own country, and in a LGBTQ community that was growing increasingly homogenous and conservative. It was a relief to live in France for a while, where I actually was foreign in a real and acceptable way.

Finally, I know you’re working on an Avengers archiving project. Can you tell Lambda readers a bit about that project and how we can get involved?

I actually wrote the book as a way to share the basic facts about the Avengers and hopefully create enough curiosity with my story to get people interested in this huge lesbian movement.

I can’t say this enough. The Lesbian Avengers were enormous! Dykes were inspired to start groups all over the world, not just in New York and San Francisco. In its heyday during the 1990s, there were at least sixty Lesbian Avenger chapters. Not much is known about them, and never will be, without your help. There was probably one in your neck of the woods. There’s a list of chapters up on the website LesbianAvengers.com and we’d welcome help from anybody at all, describing actions, collecting flyers, establishing dates. If it’s not up there. We probably don’t have it.

Of course we also appreciate donations.