Twice Militant: Lorraine Hansberry

Author: Victoria Brownworth

February 25, 2014

A Raisin in the Sun is one of the most enduring plays in modern American literature. “The play that changed American theater forever,” wrote the New York Times. The author, Lorraine Hansberry, was only 29 when it debuted on Broadway on March 11, 1959. A Raisin in the Sun was the first play written by an African-American woman to reach Broadway. There it won the New York Drama Critic’s Circle Award for best drama. Hansberry was only the fifth woman to win the award as well as the youngest playwright and first black to win it.

That play is so singular in the American theatrical canon that it ranks with other seminal American plays from greats such as O’Neill, Odets and Miller. If Hansberry had written nothing else, we would be satisfied–A Raisin in the Sun is that compelling, that good, that lasting a story. A 2004 revival of the play garnered a Tony nomination for Best Drama. Actresses Phylicia Rashad and Audra McDonald both won Tonys for their roles. The play continues to bring out the best in actors; the very definition of a classic.

But A Raisin in the Sun was not Hansberry’s only work. She did write other things–many other things–including work that displayed the side of her few knew about when A Raisin in the Sun hit Broadway: Hansberry’s lesbian self.

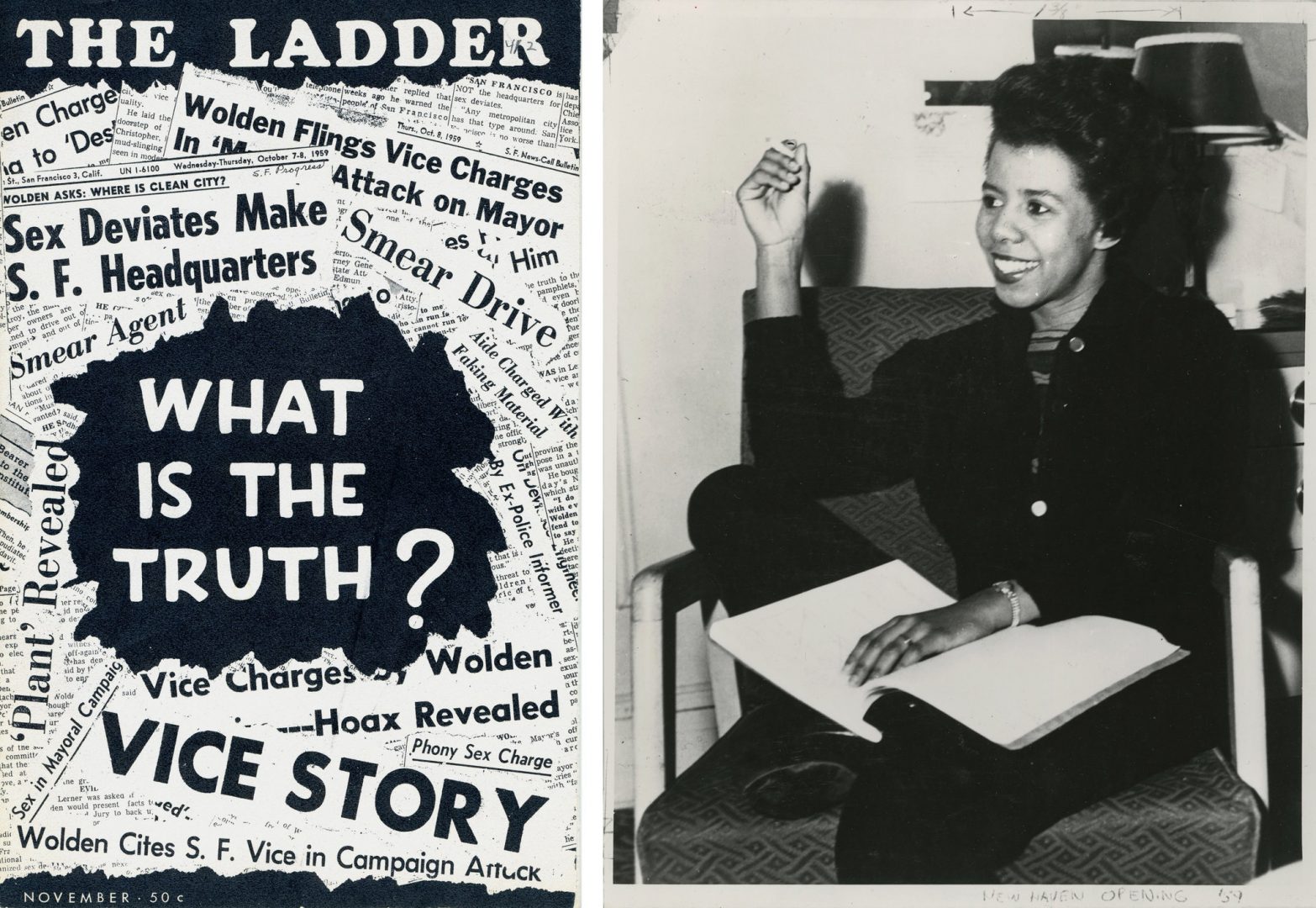

Some of this other, lesser-known writing by Hansberry is currently on display at the Brooklyn Museum, in the Herstory Gallery of the Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art. The exhibit titled “Twice Militant: Lorraine Hansberry’s Letters to The Ladder,” runs through March. The exhibit puts Hansberry’s long-hidden lesbianism on display and makes us ache for what more she might have written–what lesbian writing she might have done that was as groundbreaking as her work featuring African-Americans–had she not died in 1965 at the excruciatingly young age of 34 from pancreatic cancer.

In an interview Hansberry did with Studs Terkel, which is excerpted in the exhibit, she states: “I believe that one of the most sound ideas in dramatic writing is that in order to create something universal you must pay very great attention to the specific.”

She did that in all her writing, but never so much as in what has been revealed in the Brooklyn Museum exhibit. As she said repeatedly of herself: “I was born black and female.”

She might have added, “and lesbian.”

Lesbian voices are consistently hidden if not outright erased. Actress Ellen Page spoke about hiding her own lesbianism when she came out last week, scarcely able, still, to even say the word lesbian. In 2014.

Lesbian voices are also often misrepresented. For generations historians–even gay ones–dismissed lesbian relationships as “romantic friendships,” presumptively assuming that women weren’t capable of passionate, fully realized sexual engagements irrespective of men. (What would they do, save cuddle?) Writings by lesbians were scant–particularly by women who were not famous, like the coterie of literary and artistic lesbians in Paris in the 1920s, among those, Gertrude Stein, Alice B. Toklas, Radclyffe Hall, Djuna Barnes and Renée Vivienne.

In 1950s America, The Ladder sought to connect ordinary lesbians with other lesbians–it was the first subscription magazine for lesbians in the U.S. and was available from 1956 through 1972. It began as the newsletter of Daughters of Bilitis, the first lesbian organization in the U.S. The Ladder (the name of the magazine came from the artwork on the debut cover–line drawings showing women moving toward a ladder that disappeared into the clouds) then expanded to include women who were not members of DOB.

The names of the editors are now well-known to LGBT history: Phyllis Lyon and Del Martin, Barbara Gittings, Helen Sandoz, Barbara Grier. The initial issue was 175 copies, typewritten, mimeographed and hand-stapled, but within a year 400 copies were printed and disseminated. The audience grew far beyond San Francisco, where Lyon and Martin had founded DOB.

Women who wrote for the publication generally used pseudonyms. In interviews, Barbara Grier told me she had written for The Ladder as Gene Damon.

Lorraine Hansberry wrote for The Ladder under her initials: L. H. N. (The N stood for Nemiroff, her married name. Her husband was producer and songwriter Robert Nemiroff. Hansberry was married to him from 1953 to 1962.)

It is Hansberry’s lesbianism and her writing for The Ladder that is on display at the Brooklyn Museum, including her opening salvo: A letter to the editor which reads in part “I’m glad as heck that you exist.”

She was almost 27–just like Ellen Page–when she wrote that letter and her groundbreaking play had not yet become a hit. But Phyllis Lyon printed the entirety of her letter–it took up four of the publication’s 20 pages. It’s breathtaking to consider that confluence of events: Hansberry’s excitement as she wrote the letter; Lyon’s excitement at receiving it. The sheer frisson of herstory. Both Hansberry and The Ladder poised on the cusp of change that would culminate in the Stonewall Rebellion a little over a decade hence. Yet all these women and The Ladder itself (which was mailed in a plain brown wrapper) were entombed in their individual and collective closets. If it is still an issue for a well-known actress like Page to come out in 2014, imagine the pressures on the married, black playwright whose parents had instilled in her, “Above all, there were two things which were never to be betrayed: the family and the race.”

Hansberry had eschewed black colleges in favor of a white university. She had actually integrated her dormitory. She had married a white Jewish man. Now she was revealing her lesbianism and her need for woman-only space. She had stepped to the side of what her family had expected of her.

Hansberry wrote to The Ladder, “You are obviously serious people, and I feel that women, without wishing to foster any strict separatist notions, homo or hetero, indeed have a need for their own publications and organizations. Our problems, our experiences as women, are profoundly unique as compared to the other half of the human race.”

The specter of Hansberry’s early death looms over all that has been written by her and about her. Reading her or reading about her is muted by the knowledge that she died at the beginning of her career, yet well before its apex.What more might we have gotten from her? She’d be 84 now. A few years younger than Maxine Kumin, whom I wrote about here last week after her death. Imagine if Hansberry had had, like Kumin, another 50 years of writing amassed over a real lifetime–not the brief time that she was given? Imagine what would have come from the writer who said so simply: “Never be afraid to sit awhile and think.”

And yet there were things, things we weren’t taught in school when we learned about Hansberry and her plays.

Consider what we did get–not just A Raisin in the Sun, a classic that had such impact, it was also made into a film, starring Sidney Poitier, in 1961–but other plays, essays, poems, stories, speeches, articles. And of course those maddeningly brief glimpses into her lesbian and feminist theorizing in The Ladder.

Many have tried to deny Hansberry’s lesbianism, saying these letters prove nothing. But the totality of her texts state otherwise. She was a lesbian, and strongly so. She writes to The Ladder not as a neophyte, but as someone who has been debating the question of her own sexual orientation–as well as homosexuality itself—for some time.

“What the homosexual wants and needs is not autonomy from the human race but utter integration in it. I feel however I could be wrong about this.”

Again, she was only 26. But her analytical clarity, here, cannot be denied.

Hansberry had begun her writing career after dropping out of college at the University of Wisconsin-Madison–possibly the whitest school in America in 1948. She had refused the black college route her family had taken. (Her brother, William, founded the African Civilization Department at Howard University.) Hansberry’s father was a real estate broker, her mother was a teacher and committee woman. Both were active in the Republican Party.

Lorraine was the youngest–by seven years–of four children. In essays and interviews, Hansberry explained that because of her parents’ stature in the black community, their Chicago home was filled with a cast of notable African Americans, among them W.E.B. Dubois, Paul Robeson, Jesse Owens, Duke Ellington, and Walter White.

It was their home that forged the story of A Raisin in the Sun. Hansberry’s parents, dedicated to the cause of integration (they sent Lorraine to public schools to integrate them, rather than private schools they could well afford), had bought a house in the all-white Washington Park subdivision on Chicago’s South Side. The district was whites only and had a restrictive covenant. The Hansberrys were sued to force them out of the neighborhood. The case went all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court in Hansberry v. Lee, and while it didn’t exactly find against the Hansberrys, they were forced out of their house nontheless.

Hansberry never presented her parents as role models, however. In To Be Young, Gifted and Black she wrote, “Of love and my parents, there is little to be written; their relationship totheir children was utilitarian. We were fed and housed and dressed and outfitted with more cash than our associates and that was all. We were also vaguely taught certain vague absolutes: that we were better than no one but infinitely superior to everyone…”

Nevertheless, Hansberry also said the court case killed her father, who died when she was 15. “American racism helped kill him,” she asserted. She also said, “Both of my parents were strong-minded, civic-minded, exceptionally race-minded people who made enormous sacrifices on behalf of the struggle for civil rights throughout their lifetimes.”

Racism was an issue Hansberry wanted to address, if differently from her parents’ integration focus. Classmates at Madison said she was frequently engaged in protests. (She met Nemiroff on a New York picket line.) So when Hansberry left her white, Wisconsin college to go to New York City in 1950, it was not surprising that she became politically involved right away. She had already worked on the presidential campaign of FDR’s former vice-president, Henry Wallace in 1948, despite her mother’s demands that she not, as the Hansberrys were Republicans and Wallace was running on the Progressive Party ticket.

The pull to write was great–Hansberry has shifted her attention from art to writing. Hansberry attended the New School in New York City and also landed at Paul Robeson’s newspaper, Freedom, where she was a clerk and typist as well as an editorial assistant and writer. The paper was, like Robeson, Communist, and Hansberry got deeper and deeper into politics that combined that leftist ideology with civil rights, feminism and African liberation agendas.

In September 1951, Hansberry was an advocacy journalist, embedded with the “Sojourners for Truth and Justice,” a group of 132 black women from 15 states. The women, led by activist Mary Church Terrell, had gone to Washington to protest the treatment of black Americans. Hansberry’s article–a full page in Freedom–was a vivid, harsh accounting of the meeting between officials at the Justice Department and the women. Included among those was Amy Mallard, widow of a black WWII veteran who had been shot to death for demanding to vote in Georgia. Mrs. Mallard had testified at the trial of her husband’s killers, who were summarily acquitted.

Hansberry’s next assignment was equally grim–covering the case of Willie McGee, a black Mississippian who was executed for the rape of a white woman, Willette Hawkins. (No white man had ever been executed for rape in Mississippi.)

The case was a cause celebre and was one of the first civil rights cases argued by feminist theorist and politician Bella Abzug. William Faulkner wrote a letter on behalf of McGee and Josephine Baker, Albert Einstein and of course Hansberry’s boss, Paul Robeson, all petitioned for him.

Hansberry, then 21, covered the trial for Freedom and also wrote a poem, “Lynchsong” about the case. (Rosalee was McGee’s wife to whom he wrote prior to his execution, exhorting her to tell their children it was “to keep the Negro down” that had killed him.)

I can hear Rosalee

See the eyes of Willie McGee

My mother told me about

Lynchings

My mother told me about

The dark nights

And dirt roads

And torch lights

And lynch robesThe

faces of men

Laughing white

Faces of men

Dead in the night

sorrow night

and a

sorrow night

Hansberry traveled from that poem to A Raisin in the Sun via more reporting and a variety of stories, poems and essays. Her politics–including her feminist politics–were strong and remained so. But her hidden sexuality was not completely hidden and her feminist politics were a consistent subtext in her work, as evidenced in her second, less-well-received play, The Sign in Sidney Brustein’s Window, which has strong analogies to hers and Nemiroff’s marriage and life.

What is rarely noted in commentary about Hansberry’s work or her sexuality is that the play incorporated several of Hansberry’s themes–feminism, homosexuality, leftist politics. The Brusteins are in an interracial marriage. One of the main characters, David, is a gay playwright.

At one point in the play the following statement is made: “If somebody insults you—sock ’em in the jaw. If you don’t like the sex laws, attack them…You wanna get up a petition? I’ll sign one. But. David, please get over your notion that your particular sexuality is something that only the deepest, saddest, the most nobly tortured can know about. It ain’t–it’s just one kind of sex–that’s all. And, in my opinion, the universe turns regardless.”

In discussing the play, which focuses on a Jewish intellectual not unlike Nemiroff, Hansberry wrote, “The silhouette of the Western intellectual poised in hesitation before the flames of involvement was an accurate symbolism of my closest friends.”

Hansberry wrote other plays, like Les Blancs, a sardonic answer to Jean Genet. Unlike many playwrights of her era, she eschewed existentialism which she found both sexist and racist. Her oeuvre had always been oppression: of blacks, of women and possibly even of lesbians. Certainly the key themes in both her plays and her essays as well as her work for Freedom was succinctly anti-racist, feminist and leftist.

She had taken on some of the heavyweights of her time–not just Genet but Norman Mailer, Samuel Beckett, Edward Albee. Hansberry considered their work nihilistic and morally bankrupt–the antithesis of her own. While they used the tropes of race and sex in their work, she felt none of them–particularly Genet and Mailer–addressed the root oppression of blacks and women, but rather just appropriated them as symbols, ignoring that foundation of oppression.

For example, she writes in a poem excerpt at the exhibit:

“And at 29”

I hate

…

My loneliness

My homosexuality

Stupidity

…

Jean Genet’s plays

Jean Paul Sartre’s writing

Not being able to write

Death

Pain

…

In 1959, in the interview with Terkel, Hansberry made her comment that “the most oppressed group of any oppressed group will be its women.” Because they are “twice oppressed,” she told Terkel, they will be compelled to be “twice militant.”

She says it succinctly herself in this unpublished 1961 essay, “On Homophobia, The Intellectual Impoverishment of Women and a Homosexual ‘Bill of Rights.’”

I have suspected for a good time that the homosexual in America would ultimately pay a price for the intellectual impoverishment of women. Men continue to mis-interpret the second-rate status of women as implying a privileged status for themselves; heterosexuals think the same way about homosexuals; gentiles about Jews; whites about blacks; haves about have-nots.

She extrapolates on that theme of Otherness and marginalization in one of her letters to The Ladder, writing: “I am more convinced than ever of the depth and sincerity and—dignity—you people are determined to pursue your work with. I cannot tell you how encouraging it is.”

Hansberry continues with her critique of sexism/misogyny and how it folds together with racism. (Again, one imagines Lyons just bowled over by receiving these letters. No wonder she published them in full.)

Hansberry writes, “It is time that ‘half the human race’ had something to say about the nature of its existence. Otherwise—without revised basic thinking—the woman intellectual is likely to find herself trying to draw conclusions—based on acceptance of a social moral superstructure which has never admitted to the equality of women and therefore is immoral itself.”

She discusses her anger at butch lesbians being forced into gender conformity due to the strict dress codes of the day and notes the sexism of gay men toward women, even as she sees them as her brothers.

Hansberry was close friends with James Baldwin and one of the poetic excerpts of her work from when she was 28 reads:

I like

Conversations with James Baldwin

…

To be alone when I want to

To watch television very late at night

…

I want

To work

To be in love

…

In her letters to The Ladder, she also talks about race and about lesbians married to men, as she was to Nemiroff.

In that first letter she opines,

As one raised in a subculture experience (I am a Negro) where those within were and are forever lecturing to their fellows about how to appear acceptable to the dominant social groups, I know something about the shallowness of such a view in and of itself…what ought to be clear is that one is oppressed or discriminated against because one is “different”, not “wrong” or “bad.” This is perhaps the bitterest of the entire pill.

The pain of living marginalized that made A Raisin in the Sun a classic is stunningly evident here.

Was it because she was anonymous that she felt she could say what she wanted on the pages of The Ladder? Or was it that Hansberry had finally come home–into the embrace of that community of women she had referenced in her first letter–to the “safe space” of a women-only venue to extrapolate these musings? There she was–the daughter of integration activists, herself a leftist intellectual of the sort she wrote about in Sidney Brustein’s Window. But she was isolated–by her blackness, her femaleness, her lesbianism.

Her self-awareness and her intrinsic sense that sexism and homophobia would forever intersect is evident all over that essay on homophobia where she also writes: “Men, as a sex, find themselves socially stagnant and trapped into incredible patterns with conformity that dictate what and how their ‘manliness’ should be in order to hold their place over the lesser…The relationship of anti-homosexual sentiment to the oppression of women has a special and deep implication.”

Her adoring husband who kept her memory alive every day of his own life until his death in 1993 gave her plenty of space and even after their divorce they continued to work together and spend time together.

Nemiroff said Hansberry’s “‘homosexuality’ was not a peripheral or casual part of her life but contributed significantly on many levels to the sensitivity and complexity of her view of human beings and of the world.”

How painful it must have been for him to state that, keeper of her flame that he was and excluded as he was by her lesbianism.

While she was alive, Nemiroff could open some doors for her with regard to the theater, but he could never provide the freedom of the platform that The Ladder did. Had she lived, she would have had to extricate herself from his adoration and fealty in order to thrive. And her lesbianism would clearly have influenced her work more and more. It was, after all, when she began writing to The Ladder that Hansberry separated from Nemiroff, although they didn’t divorce until years later.

Perhaps it is Nemiroff she is thinking about when she wrote, presuming there would always be men who believed women deserved equality with men, “If by some miracle women should not ever utter a single protest against their condition, there would still exist among men those who could not endure in peace until her liberation had been achieved.”

There is no point where Hansberry writes secret lesbian texts, however. We don’t have those. We have these bits and pieces, this collage of letters, essays, poems, lists. There will never be revealed some larger lost lesbian writing, maddening as that is.

We are left, instead with this, which she wrote in 1962:

I regret

That love really is as elusive as everybody over 30 knows it to be

…My consuming loneliness

All the friggin’ hurts in this world

That a certain lady let my letter be read!

The shallowness of the people who have come into (and lately been expelled from)my life.

I like

69 when it really works

the first scotch

the fact that I almost never want the third or even the second when I am alone.

Praise fate!

The inside of a lovely woman’s mouth

The way little JW looks in the movies

Her coquettishness

Her behind–those fresh little muscles

Parts of the lingering memory of a betrayer.

I am proud

that I am losing some of those fears

that I struggle to work

hard

against many, many things

and on my own

of my people

I should like

to be utterly, utterly in love

to work and finish something

The emotion in those lines is crushing for its raw certitude that she is somehow missing out on a part of life open to everyone else.

We know Hansberry had myriad affairs with women during the period when she was married to Nemiroff and living in New York’s Greenwich Village, but we know little about that time. The longest of these is said to have been with Dorothy Secules, to whom she is alleged to have left a significant portion of her estate. But there are no love letters, no diary accountings, not even a former lover coming forward to tell all. There are just these painful snippets from a life just getting started, of a black lesbian writer stepping toward a door just beginning to open onto a range of vistas and experiences.

She kept thinking, deconstructing her ideas, her world. As she wrote, “Do I remain a revolutionary? Intellectually–without a doubt. But am I prepared to give my body to the struggle or even my comforts? This is what I puzzle about.”

Despite the cheerful, excited tone of the letters to The Ladder, the conflicts in Hansberry’s life left her discontented and disconnected as the above poem shows. Why wasn’t she embraced by any movements she championed–black liberation or feminism? Her feelings of isolation are exemplified in this excerpt from her journals dated Easter 1962:

Yesterday I was alone. And so, I did some work; I don’t really remember what. And then in a fit of self-sufficiency went shopping in the supermarket and bought food: liver, steak, chops. I rather knew the kind of weekend that was coming. But was not depressed… The being alone is better. That is what one has to learn ultimately. It is really is better to be alone; it is horrible–but it is better.

Tonight worked. Productively. But can’t get excited about any accomplishment tonight.

Worst of all, I am ashamed of being alone. Or is it my loneliness that I am ashamed of? I have closed the shutters so that no one can see. Me. Alone. Sitting at the typewriter on Easter Eve; brooding; alone. Upstairs I will keep the drapes drawn. No one must know these hurts. Why? I shall wash my hair. It is helping my skin. I shall be beautiful this time next year: long hair and clear skin. And I shall still be lonely. On Easter eve. At the typewriter…

Time ran out on her–her work, her happiness. Two surgeries failed to conquer the pancreatic cancer discovered suddenly and late. We are left with her work–strong, yet not nearly enough–and the woman: magnetic, compelling, enigmatic, brilliant.

The title of her play, A Raisin in the Sun, is taken from the Langston Hughes poem:

What happens to a dream deferred?

Does it dry up

Like a raisin in the sun?

In “To Be Young, Gifted and Black,” the song she wrote for Hansberry after her death, singer and friend Nina Simone says simply:

To be young, gifted and black,

Oh what a lovely precious dream

To be young, gifted and black,

Open your heart to what I mean

Hansberry did not defer her dream. And her heart–so easily and readily broken by the JWs and their coquettishness–was open wide, giving us as much as she could in the time she had. Oh if only it had been more.

Photo via NYPL