Writing Out the Holocaust: Auschwitz at 70

Author: Victoria Brownworth

January 29, 2015

Mine is the first generation of post-Holocaust children–children born in the late 1950s and early 1960s of parents, one or both, who had somehow, miraculously, survived what six million Jews and millions of others, including “homosexuals,” did not.

My inner-city public high school class was filled with the children of immigrants, girls whose parents spoke no English or who spoke it in the thick accents of Eastern Europe or the Soviet bloc. Among my closest friends were several Jewish girls. Girls, I would soon discover, whose parents were Holocaust survivors.

I shall never forget the first time I saw the tattooed numbers on the inside of one friend’s mother’s arm. Teenagers are especially attuned to the forbidden. Even as the numbers were shown to me–my friend’s mother was feeding us an after-school meal and her sleeve was accidentally pulled up, baring her secret–I knew I was not supposed to have seen. That I was an unchosen, unbidden witness to a small but irrevocable symbol of atrocity.

The glimpse into the darkest side of human nature was there, in blue ink, on her arm. Not the beautifully calligraphied numbers of today’s tattoo industry, but roughly, hastily drawn numbers, five of them, as if someone had quickly jotted down part of a phone number and then was called away. A European seven, four others.

It would not be long before I would see a similar set of numbers on the arm of another friend’s mother. It would not be long before I would go to the library to investigate what I had heard of, but not really known as a 13-year-old exile from nearly a decade of Catholic school: The Holocaust. The Shoah.

As a student of history I knew to start with the details, because that is where history lies–in the interstitial spaces between our best, most courageous selves and our most base animalistic selves.

I remember lying on my bed at home, reading the disturbing details of what was done to women and men at the camps. Torture. Experimentation. Simple cruelties. Extreme barbarism. Incomparable suffering meted out by one set of human beings upon another. Dehumanization. The descriptions were vivid and horrific and they have never left my consciousness.

Nor did the Holocaust fiction I read then–those books drew pictures that were visceral, brutal canvases of all we can do and have done to each other. Elie Wiesel’s Night. Jerzy Kosinski’s The Painted Bird and Steps. Stark, harrowing stories. Unforgettable images. Tales of guilt and betrayal and hatred and envy and madness.

These books exemplified the Holocaust not just because they were written by Jews who had managed to survive it, but because they situated their tales in the reality of a world that had exiled humanity for the duration. How else to explain what had happened? How else to explain how the world sat silent as it happened?

The Diary of a Young Girl by Anne Frank was probably the first book I ever read in which lesbianism–or the intimation of it–appeared. I imagined the young Anne–my own age–as she hid from death yet dreamed of life. I imagined her wanting to escape, to grow up to love another woman, to explore everything beyond Miep Gies’s attic.

I imagined my friends’ mothers had been like Anne–vivacious pubescents ready for the breadth of experience life had to offer them. But even my naive self could see they have been changed irrevocably by the horrors they had witnessed and survived. A piece of them was gone. Irretrievable.

I’m not sure when I first realized that gay men and lesbians had also been targeted victims of the Nazis. When I first saw Liliana Cavani’s brilliant and controversial film, The Night Porter, it was brought vividly into my consciousness.

Gay men were in the camps. Which meant lesbians were also there, hidden, as we have been throughout history.

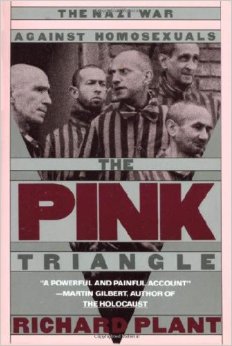

Richard Plant’s 1986 historical memoir, The Pink Triangle: The Nazi War Against Homosexuals was the first book to situate homosexuals as victims of the Holocaust and specific, rather than accidental targets of the Third Reich. Plant, a gay Jew who had escaped Nazi Germany in 1938 at the age of 28, didn’t write of his Holocaust experiences until he was in his 70s. He died a few years after The Pink Triangle was published.

I cannot help but wonder why it took him so long to write that story, to reveal that slight of history–the erasure of our names from the book of the Nazi dead.

But then I remember my friend’s mother, her sleeve pulled back down to her wrist the second time her arm stretched across us at the table. Some revelations come slowly. Some revelations are so personal, you break open in revealing them.

The Pink Triangle documents what happened to Jews in the camps. Dehumanization was paramount. All body hair was shaved off. They were dressed in uniforms that had no semblance of power–that were really pajamas. Arms or chests were tattooed with identifying numbers, because they were no longer people. And they wore color coded badges so the guards could tell why they were there.

The gays got pink. Lesbians–known lesbians–got either red or black, symbols of dissidents and those deemed anti-social by the Nazis.

As Plant’s book explained, homosexuals were a natural target because after the Jews, they were the most obvious exemplars of the Weimar Republic and everything the National Socialist Party deemed corrupt and tainted and not wholly or wholesomely German or Aryan.

As we see in Christopher Isherwood’s Goodbye to Berlin and Berlin Stories, on which Cabaret would later be based, the Weimar Republic was rife with gay men and lesbians in visible, intentional relationships. The gay and lesbian subculture of Berlin was an affront to the burgeoning Nazi party.

As can be seen in France, Britain and the Netherlands today, the far right nationalist political parties are always fearful of racial or cultural “taint.” As Plant described it in The Pink Triangle, Jews exemplified this as did lesbians and gay men. The racialist theories propounded by the Nazis elided anyone who wasn’t Aryan as “contragenic”–and therefore to be annihilated. The way to purify a race was to excise anyone who was deviant.

What could be more deviant than the known “deviants”–the gay men and lesbians propelling the arts and culture of that era? They had to be eradicated. Their words and art were too subversive and countermanded the goals of the Third Reich.

As Plant connects the historical dots, Nazi homophobia was like Nazi anti-Semitism. It was ineluctable. When the Nazis ousted the Weimar Republic from power, its heroes–be they true or cultural or even just celebrities–had to be made an example of. In Alan Cumming’s brilliant evocation of Cabaret’s Emcee, which I was fortunate enough to see in one of its incarnations, there is a dark and desperate shift in tone from the early part of the play to the final act. Cumming is the symbol of the gay man about to be loaded onto a cattle car.

As Plant explicates, Germany could be the mighty force of militaristic power it once was before being emasculated by the allies and the Jews, or it could be the pansy brigade the Nazis believed it had become because gays had infiltrated and destroyed the strong heterosexual spine of the nation.

At the core of this anti-gay movement was the leader of the SS, Heinrich Himmler, was also headed the camps. As Plant describes him, Himmler is pathological in his homophobic zeal. He comes to believe that all aspects of homosexuality are infectious, a disease that must be eradicated for Germany to ascend again. Plant writes that Himmler believed gay men especially were “endangering the National Sexual Budget” and that while he believed that lesbians could be readily turned into haus frauen, gay men were inhibiting the propagation of the Master Race.

Re-reading Plant now, at the 70th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz, where more than a million people, mostly Jews, were slaughtered, it seems laughable. Like a Sarah Palin rant at a Tea Party caucus. But Germans were desperate to regain their place in the world hierarchy and the Nazi plan made sense to many. All those good Germans we have heard about were like the good French–nearly non-existent, the French Resistance so widely touted in revisionist histories paling beside the collaboration of the Vichy government.

Yet would we have the totality of Existentialism without the Holocaust? It seems unlikely. Jean-Paul Sartre, Simon de Beauvior and Albert Camus were the triumvirate of the existentialist movement. Their work, while it may be read in part as an absolution of French involvement in not only the annihilation of the Jews but in the subsequent colonialist genocide in Algeria, certainly finds its roots as Holocaust literature, if not Holocaust philosophy. How do we read Camus’s L’etranger outside of the context of the Europe of the Bliztkrieg and Anschluss? How much of a parable is Sartre’s No Exit, written as it was in 1944, for all that was happening in a Europe controlled and framed by Hitler’s Götterdämmerung?

Yet the reality of the Holocaust–for Jews, for gay men and lesbians, for the Romanys who were also nearly wiped out–is what we read in the memoirs, in the novels, in the meticulously detailed oral histories–oral histories like the ones collected by Dr. Jennie Goldenberg through the Transcending Trauma Project in Philadelphia. In the Routledge collection, Transcending Trauma, co-authored with Nancy Isserman and Bea Hollander-Goldfein, the impact of the Holocaust on survivors is detailed and extrapolated upon.

Goldenberg has given papers on her research and hundreds of interviews with Holocaust survivors over two decades in Britain, Israel and throughout the U.S. Based on 275 in-depth life histories with Holocaust survivors, their children and grandchildren, Transcending Trauma explores how these survivors and their ability to move beyond the brutality they experienced can become models for other trauma victims–and though this is not stated, perhaps, victims of more genocide.

Like the slow and steady genocide which is occurring now in Nigeria, Uganda and Iran, of gay men and lesbians while the entire world once again–despite the social media that did not exist 70 years ago–shrugs and looks away. The day before Holocaust Remembrance Day, President Obama was arm in arm with Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi–who championed Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code which gay and lesbian sex illegal and punishable by imprisonment.

Is this genocide in the millions? It is not. Are gay men and lesbians being dragged from their homes and removed from their communities, often permanently. They are.

The erasure of gay men and lesbians from the memorializing of Holocaust survivors wasn’t intentional–and yet it still happened. Plant’s book opened the door to a plethora of books by gay men and lesbians about the interconnectedness of the genocide of Jews and the attempted genocide of gay men and lesbians by the Third Reich.

Had Plant not written his book–propelled by his aging and haunted by his own memories of escaping Hitler–would these gay men and lesbians have been lost to history? It’s impossible to know. Just as one wonders if Plant had written The Pink Triangle twenty or even ten years earlier, if we would have more oral histories of gay and lesbian Holocaust survivors, like the ones of straight survivors acquired by Goldenberg and her colleagues.

Books like An Underground Life: Memoirs of a Gay Jew in Nazi Berlin, by Gad Beck and Frank Heibert or The Man Next Door by J. Tomas, or I, Pierre Seel, Deported Homosexual: A Memoir of Nazi Terror by Pierre Seel and Joachim Neugroschel, Liberation Was for Others: Memoirs of a Gay Survivor of the Nazi Holocaust by Pierre Seel and Joachim Neugroschel or Confronting History: A Memoir by George L. Mosse and Walter Laqueur

At the U.S. Holocaust Museum, efforts to record the lives of gay and lesbian survivors have been difficult because they had to remain hidden, even after liberation. Paragraph 175 of the German Penal Code instituted by the Nazis criminalizing homosexuality was not rescinded until 1969.

The museum began recording oral histories of gay Holocaust survivors in the 1990s. Of the estimated 100,000 to 150,000 gay men and lesbians imprisoned under Germany’s Nazi laws, fewer than 15 were alive in 1996 when efforts were being made to have them noted in the museums archives. But it was the Holocaust Museum’s efforts that led to the 1994 recovery of the first pink triangle–the symbol sewn to gay prisoners’ uniforms in concentration camps.

According to the museum, the lover of a gay camp survivor living in Vienna found the pink triangular piece of cloth numbered 1896, along with handwritten notes written on the day of liberation from Flossenberg concentration camp, upon his partner’s death. The triangle and the notes are on permanent loan to the museum.

And so our history–as gay and lesbian Holocaust survivors, as Jews who were also gay or lesbian but imprisoned as Jews, not as gays or lesbians–is largely lost to us.

Popular lesbian romance novelist Trin Denise is one of many gay and lesbian writers trying to fill in that interstitial narrative with fiction. In March her new novel The Women of Birkenau-Auschwitz will be published alongside Ravensbruck: Life and Death in Hitler’s Concentration Camp for Women by Sarah Helm. These two books join Laughing Winds by Rose Christo, Aimee & Jaguar: A Love Story, Berlin 1943 by Erica Fisher, Women in the Holocaust, by Dalia Ofer and Lenore J. Weitzman, In Memory’s Kitchen: A Legacy from the Women of TerezinMar by Michael Berenbaum and Cara De Silva and the recently released, Hitler’s Furies: German Women in the Nazi Killing Fields by Wendy Lower and Lovers at the Chameleon Club, Paris 1932 by Francine Prose.

There is perhaps no single more important historical eyewitness accounting–beyond that of Anne Frank and Elie Wiesel–than those recorded in Claude Lanzmann’s singular Shoah. Lanzmann’s autobiography, The Patagonian Hare, is an addendum to that book and another book of tremendous import in the cataloging of Holocaust literature. Lanzmann, a French Jew, explains early on in the book that Jews learned how to hide in anti-Semitic France.

“Hiding behind a pillar in the school playground I watched–petrified, making no attempt to intervene, terrified that I might be discovered–as my classmates all but lynched a lanky, red-haired Jew named Lévy who had all the features of pre-war anti-Semitic caricatures. They were twenty against one and they beat him until he bled.”

In Night, Wiesel recounts a similar horrible beating he witnessed and in which he did not intervene, for fear of being beaten just as badly himself. That beating was of his father in the bunk below him at Auschwitz.

This is in no way the canon of Holocaust literature. I have not mentioned anything by the extraordinary Primo Levi or Lev Raphael’s compelling My Germany: A Jewish Writer Returns to the World His Parents Escaped, or Markus Zusak’s The Book Thief or John Boyne’s The Boy in the Striped Pajamas or all the many brilliant writings of Cynthia Ozick.

I have not mentioned one of the pivotal philosophical treatises of our time, which is a post-Holocaust study, Hannah Arendt’s endlessly controversial Eichmann in Jerusalem, from which the concept of the “banality of evil” comes.

But that book is a fitting place to end, because I do not now nor have I ever agreed with Arendt’s existentialist perspective on evil. I retain the belief that evil is in fact, extraordinary. One has only to read just one of these books. There is Wiesel, who I was fortunate to have worked with briefly when he wrote a preface to a book I was editing on Dietrich Bonhoeffer, who details his own journey from darkness to light in the Night trilogy. There are the suicides of survivors Primo Levi and Jerzy Kosinski, which speak to the inescapable nature of the horrors they endured. There is that bright and lovely diary of that very young girl, Anne Frank–how can we not mourn her slaughter?

There is Plant at nearly 80, finally writing his premiere work, swinging wide the closet door not just on his own life, but on that of all the gay men and lesbian women lost to history, murdered by the Nazis.

There is no book about the Holocaust that doesn’t speak again and again to the breadth of the horror. Banal? Perhaps an unmoved and unmoving Eichmann in the dock made Arendt think this as she reported for the New Yorker in 1961. But my memory of those numbers tattooed on the pale slender arm of my high school friend’s mother spoke to the antithesis of that. It spoke to the monstrousness evil and how it could seep into a crisp, well-kept kitchen in Northeast Philadelphia from a world away.

As we read more and more books about what transpired over those years throughout Europe, as we read and then view Lanzmann’s extraordinary history, Shoah, this is what we learn: That women and men and yes, children were dragged from their homes and sent to their deaths. There were few protests. Far more indicting than Eichmann in Jerusalem is Lanzmann’s Shoah, where we hear the witnesses to the genocide in their own words. Yes, they knew. No, they did not do anything.

And we are left to wonder, can it happen again?

Of course it can. Because evil is not in the least banal. It is extraordinary. And it feeds on the resentments and bitterness of ordinary people who want a scapegoat for their problems and that of their societies. Throughout Africa and Asia today, lesbians and gay men are being brutalized and murdered, some in state-sponsored killings, some in small vestiges of the Kristallnacht that sundered German Jews from their neighbors in a single night so terrifying, thousands must have contemplated suicide rather than face whatever might come next.

Writing out the Holocaust, the Shoah, has disallowed history and the world to forget. How can we watch millions march in France in solidarity over the murders of 17 and not remember that no one left their homes to protest the slaughter of millions?

What we learn from reading the literature of the Holocaust is that evil is not banal, but it is pandemic. It is in our very DNA as humans. And can, as it did in a Germany in economic tatters in 1929, take only some small twist of historical fate to trigger it and turn us back to what we once were–animals.